PORTLAND, USA, Jul 04 (IPS) – It is time for countries, especially those with slow growing and ageing human populations, to welcome androids, i.e., humanoid robots with human-like appearance and behavior, including speech, sight, hearing, mobility, and artificial intelligence.

Androids would not only complement and broaden a country’s labor supply, but they would also increase productivity, lower costs, raise profits, offer instruction, reduce accidents, assist in disasters, and provide safety, policing, firefighting, and security.

The introduction of androids into human societies would be especially beneficial for slow growing and ageing populations. Following the rapid population growth of the 20th century, demographic growth rates are slowing down, and populations are ageing globally.

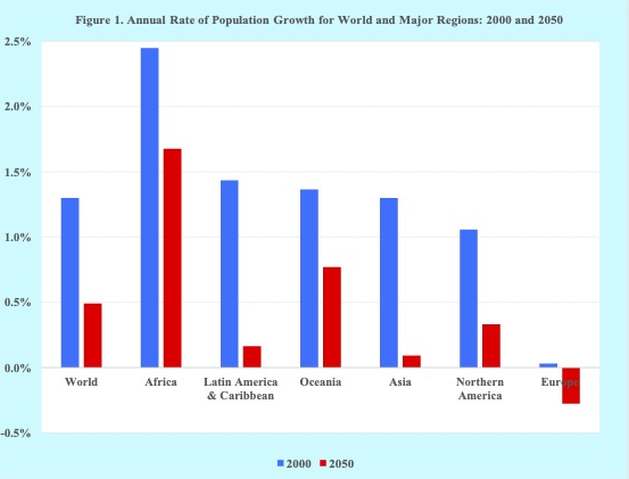

Whereas world population was growing at an annual rate of 1.3 percent at the start of the 21st century, by midcentury the rate is expected to decline to 0.5 percent. The annual population growth rates of major regions are expected to decline over that period, with Europe’s population growth rate projected to decline to -0.3 percent (Figure 1).

With respect to population ageing, countries worldwide are becoming older than ever before. The proportion aged 65 years and older for the world, for example, is expected to more than double during the first half of the 21st century from approximately 7 percent in 2000 to 16 percent by 2050.

Among the major regions, the populations of Europe and Northern America are the most aged. During the first half of the 21st century, their proportions aged 65 years and older are expected to nearly double, reaching 28 and 23 percent by 2050, respectively (Figure 2).

Over the past decades various types of androids, or humanoid robots, have appeared in films, books, video games, and futuristic exhibitions. However, technology firms have been comparatively slow in bringing to market the latest research and progress in androids, including robotics, artificial intelligence, conversation, bipedal locomotion, and related technologies.

The only notable exception to the use of androids has been the sex industries. Those firms have jumped ahead with the rapid development of “sexbots”. Those androids are lifelike robots or dolls with humanoid form, body movements, artificial intelligence, hearing, sight, speech, and designed to have sexual relations with humans.

The market for sexbots is believed to be huge, with some convinced they are the future of sex. The realistic looking sexbots have artificial intelligence for simple conversation, are programmed to imitate basic human emotions, and can perform sexual acts with humans.

A recent study in the United States, for example, found that 40 percent of adults would have sex with a sexbot at least once to try it. Men were 21 percent more likely than women to say that they would have sex with a sexbot.

Most people are well accustomed to interacting with artificial intelligence on their cellphones, computers, and other electronic devices. Today most of those communications, which are provided both orally and by text, center on providing directions, information, explanations, purchases, games, music, entertainment, social activities, and various sorts of data.

Like the use of robotics to manufacture goods and provide services, androids could be utilized to perform a wide range of activities and services, including tasks that are boring, repetitive, hazardous, and dangerous. Already robotic devices have driven millions of miles autonomously, participated actively in space exploration, and reduced boredom and injuries to humans by carrying out dull, difficult, and dangerous tasks.

Androids could perform a variety of jobs, such as receptionist, salesclerk, guard, attendant, translator, and informant. Androids could answer basic questions, direct people to offices and individuals, remember names and faces, translate languages, log entry information, make phone calls, assist in rescues, monitor people’s health, provide caregiving, and alert authorities when human intervention is needed.

For example, the android, Nadine, is a receptionist at a Singapore university welcoming visitors and answering questions. The android, Erica, is a newscaster on Japanese television reporting the daily news and events and Sophia is the first android to be granted citizenship by Saudi Arabia.

Androids at a field hospital in Wuhan, China, perform services, measure temperatures, disinfect devices, deliver food and medicine, and entertain patients. And the android, Kime, is a beverage and food server in Spain that in addition to serving food can pour 300 glasses of beer per hour.

In addition to performing routine tasks and providing services, androids could be utilized to reduce feelings of loneliness, which has increased as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

For those individuals suffering serious loneliness, including older persons limited by dementia and illness, androids could offer conversation and also provide companionship to those lacking a partner. Androids could also offer entertainment as well as facilitate social interaction.

Furthermore, the presence and interactions with androids can help to reduce feelings of stress, encourage wellbeing activities, and improve mental functioning. Androids could also monitor human behavior and health status.

Androids can also be available 24/7. Moreover, unlike humans, androids do not become frustrated, impatient, or angry. And as androids are not judgmental, prejudiced, or biased toward human behavior or appearance, people may feel freer to express their true feelings and thoughts.

In addition, androids could assist people with functional limitations. With speech, sight, hearing, location, and movement, androids can aid and help those with limited or lacking certain functions for daily living.

Despite androids potentially being able to contribute and enhance workplaces and households, concerns, fears, and reluctance persist about their use. For example, some are concerned that androids would replace workers as has been the case with the increased use of robotics in manufacturing, especially by the auto industry.

However, while certain jobs will be reduced and workers displaced, employment opportunities are expected to increase in other areas of the economy. For example, while the global number of the robots in manufacturing in 2021 had grown to 126 per 10,000 employees, or nearly double the level in 2015, employment opportunities have continued to expand.

Also, the numbers of robots per 10,000 employees in many advanced countries have reached substantially higher levels, such as 932 for South Korea, 605 for Singapore, 390 for Japan, and 371 for Germany. Nevertheless, demand for labor in those countries remains high and unemployment levels are comparatively low (Figure 3).

Ethical questions have also been raised concerning the introduction of androids into human societies. For example, given that their appearance, intelligence, speech, and behavior will resemble humans, some have asked whether androids should be endowed with personhood that would entail certain rights, duties, and special laws.

While such ethical questions are not immediate concerns, similar questions are now being raised about the responsible use of artificial intelligence, such as facial recognition technology. However, some have suggested that androids rather than being feared may become allies of humans.

Still others have expressed fears that androids with artificial intelligence could revolt and harm humans. Those fears, which have been the plots in some popular science fiction films and books, tend to be highly exaggerated. Artificial intelligence achieving self-awareness or becoming sentient is unlikely any time soon and software safeguards could shut down an android.

Nevertheless, some continue to stress dangers and express warnings about the possibly imminent development of androids with machine intelligence greater than that of humans. Sentient machines, they contend, pose a greater likely threat to human societies than climate change, nuclear proliferation, or pandemics.

Proto-type androids have been introduced in various countries, including China, Germany, Iran, India, Japan, Russia, Singapore, South Korea, and Spain, and the United Kingdom. Many of the leaders in those countries have recognized the vital functions that androids could perform for societies and the market for androids is believed set for rapid expansion.

It’s time for countries to facilitate and promote the inclusion of androids in business establishments, government offices, public places, and personal households. Welcoming androids into human societies will advance the technological futures of countries as well as contribute to addressing slow growing and ageing populations.

Joseph Chamie is a consulting demographer, a former director of the United Nations Population Division and author of numerous publications on population issues, including his book, “Births, Deaths, Migrations and Other Important Population Matters.”

© Inter Press Service (2022) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source