LIMA, Nov 24 (IPS) – This article is part of IPS coverage of the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, celebrated Saturday, Nov. 25.”The Latin American and Caribbean region has made many advances in the fight against gender violence, but now we are facing reactions that show that our rights are never secure and that we must always be on the alert to defend them,” said Susana Chiarotti, a member of Mesecvi’s Committee of Experts.

The Committee of Experts is the technical body of the Follow-up Mechanism to the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence against Women (Mesecvi), known as the Convention of Belem do Para, which will celebrate its 30th anniversary in force in the countries of the region in 2024. The committee is made up of independent experts appointed by each state party.

Chiarotti summed up the regional situation of progress and setbacks in a conversation with IPS from her home in the Argentine city of Rosario, ahead of the United Nations’ Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, commemorated on Saturday, Nov. 25.

Gender violence violates the human rights of one in four women in this region with an estimated female population of 332 million, 51 percent of the total, and escalates to the extreme level of femicide – gender-based murders – which cost 4050 lives in 2022, according to figures confirmed Friday, Nov. 24 by the Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean.

Likewise, UN Women‘s regional director for the Americas and the Caribbean, María Noel Vaeza, told IPS from Panama City that the emblematic date seeks to draw the attention of countries to the urgent need to put an end to violence against women once and for all by adopting public policies for prevention and investing in programs to eliminate it.

She pointed out that Nov. 25 is the first of 16 days of activism against gender-based violence, which run through Dec. 10, Human Rights Day.

Vaeza said that less than 40 percent of women who suffer violence seek some kind of help, which clearly shows that they do not find guarantees in the prevention and institutional response system and therefore do not report incidents.

“This has serious consequences for their lives and those of other women, as the perpetrators do not face justice and impunity and violence continue unchecked,” she said.

Vaeza said that, despite these worrying trends, there is more evidence than ever that violence against women is preventable, and urged countries in the region to invest in prevention.

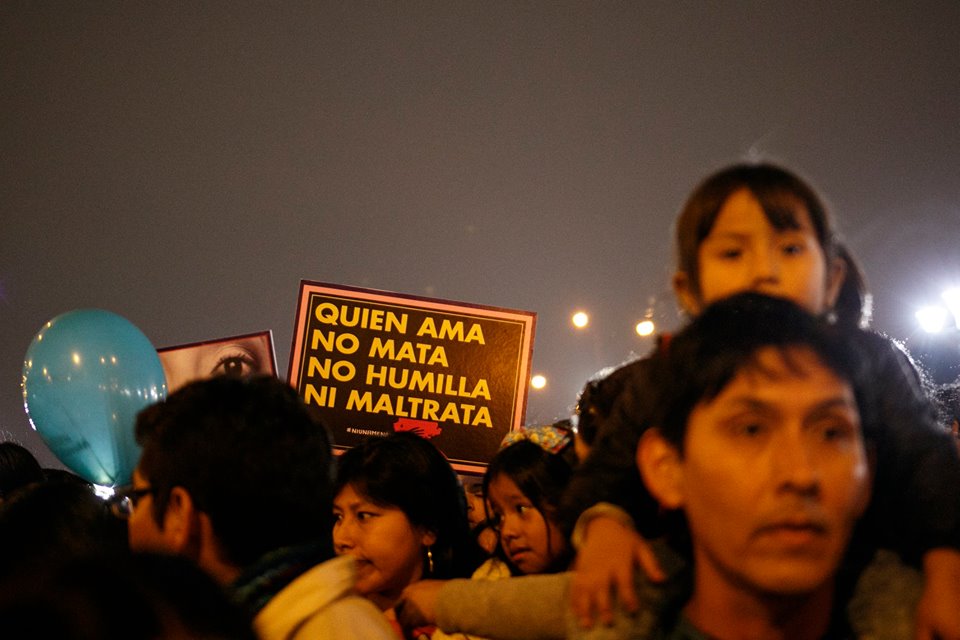

“The evidence shows that the presence of a strong, autonomous feminist movement is a critical factor in driving public policy change for the elimination of violence against women at the global, regional, national and local levels,” said the UN Women regional head.

She explained that many studies have shown that large-scale reductions in violence against women can be achieved through coordinated action between local and national prevention and response systems and women’s and other civil society organizations.

So in order to move towards regulatory frameworks and improve the institutional architecture and budget allocations to prevent, respond to and redress gender-based violence, strengthening the advocacy capacity of feminist and women’s movements and organizations is indispensable.

She also mentioned that whenever progress is made, there are setbacks as well, and “unfortunately history shows us that social changes against things like machismo/sexism and violence require the efforts of society as a whole and plans and policies that give answers to the victims today, but also make it possible to improve the system in the medium and long term.”

Vaeza stressed that violence against women and girls remains the most pervasive human rights violation around the world. Its prevalence worsened in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and is growing further due to the interrelated crises of climate change, global conflicts and economic instability.

She also mentioned the proliferation of new forms of violence and the persistence of those “who believe that we do not have to guarantee women’s human rights, and organize themselves, and in the region we have situations such as attacks against women human rights defenders and activists that have become more frequent.”

Vaeza, from Uruguay, underlined that there is more evidence than ever that it is possible to change this reality and that in order to have peaceful societies, reducing inequality and poverty is key, and all this will depend on advancing gender equality and the rights of those who have historically faced discrimination.

They are mainly, she said, women living in poverty, indigenous women, women of African descent, rural women, women migrants, and women and girls with disabilities.

Strong reactions to progress

Chiarotti said: “I have been with Mesecvi for 20 years and I can see the changes. Let’s remember that it was only in 1989 that laws on violence against women began to be enacted and that we did not have services, shelters, specialized courts and even less a specific Convention to address this issue, which was the first in the world.”

The lawyer and university professor emphasized that in 40 years the women’s movement has put the issue of violence against women on the public agenda and has made such huge strides that “we could be called the most successful lobby in history in positioning an issue in such a massive and global manner.”

And she added that “we did not believe then, in 1986, 1987 or 1988, that the phenomenon had permeated all structures, not only the intimate sphere; there was symbolic, institutional, political and many other forms of violence, which led us to demand more answers, especially from the State, which, being patriarchal, admitted women only with forceps.”

Chiarotti, who is also a former head of the Latin American and Caribbean Committee for the Defense of Women’s Rights (Cladem), warns that they are now facing reactions to the extent that unimaginable alliances have arisen to stop them, such as that of the Vatican with conservative evangelical churches and far-right groups.

She also mentioned the decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that in June 2022 overthrew the right to abortion in that country, which had been in force for almost 50 years.

“That makes you realize that our rights are never secure, that we must always be on the alert to defend them. And it is difficult for a movement that is cyclical, that has waves, that rises and falls, to be always alert,” she said.

In addition, she mentioned the recent victory of the candidate Javier Milei as future president of Argentina and the dangers he represents for women’s rights, sexual diversity and the historical memory of human rights abuses.

“This will not be the first time that this people, and women especially, will enter a stage of resistance, because we have been resisting misogynistic attacks and fighting for life for centuries, but we have a very hard time ahead of us,” Chiarotti said.

She added that Latin America has fragile democracies that are only a few decades old and in crisis, which impact women’s rights. “Many of our countries came out of dictatorships, the longest has had 50 or 60 years of democracy. We will have to work to defend democratic institutions, to use them to defend our rights,” she said.

Prevention: a task eluded by the States

The expert argued that since the work of preventing gender-based violence is more costly and time-consuming than that of punishment and less politically profitable, the efforts of countries are weak in this area despite their importance.

“Limiting the work to punishment and addressing incidents is like seeing a big rock that people stumble over and bang up against, and they are cured and taught to go around it, but without removing it from the path. Without prevention we will always have victims because the discriminatory culture that reproduces violence will not be transformed,” she warned.

But even adding up what countries invest to address and eradicate violence against women in the region, none of them reach one percent of their national budget according to the Third Hemispheric Report published by Mesecvi in 2017, a proportion that has apparently not changed since then.

In September of this year, the United Nations published a study showing that an investment of 360 billion dollars is needed to achieve gender equality and women’s empowerment by 2030, established as one of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This would help to eliminate the scourge of gender-based violence.

© Inter Press Service (2023) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source