PORTLAND, USA, Jun 23 (IPS) – Why aren’t more women angry about their subordination, discrimination, and unequal treatment in the 21st century? Of course, some of the world’s women are angry, but they are comparatively few.

Women represent half of the world’s population and clearly play vital roles in humanity’s development, wellbeing, and advancement. Yet, women continue to experience discrimination, abusive treatment, misogyny degrading slurs, and subordinate roles in virtually every major sphere of human activity.

Despite their treatment, discrimination, and subordination, most women aren’t expressing anger. If the situation between the two sexes were reversed, men would certainly be angry and would no doubt take the necessary steps to change the inequalities.

Article 2 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted nearly seventy-five years ago applies all rights and freedoms equally to women and men and prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex.

Some 40 years ago, the international community of nations adopted the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women. And more recently, the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 5 aims to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.

Notwithstanding those various declarations, international agreements, conventions, platforms for action, and the progress achieved in recent decades, women continue to lag behind men in rights, freedoms, and equality.

From the very start of life in some parts of the world, baby girls are often viewed less favorably than baby boys. In many societies boy babies continue to be preferred over girl babies. In too many instances the preference for sons has resulted in sex ratios at birth that are skewed in favor of males due to pregnancy interventions by couples.

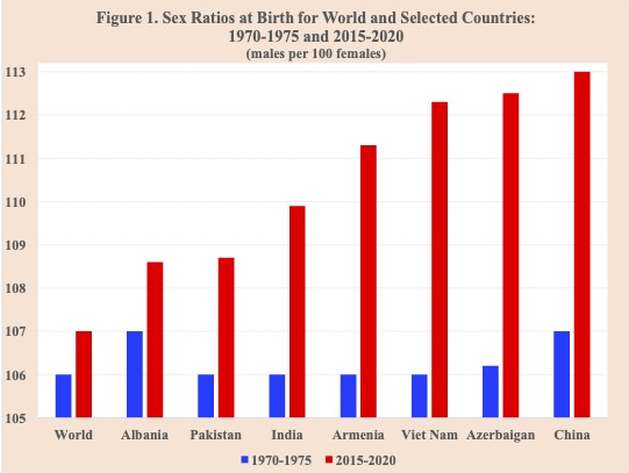

The natural sex ratio at birth for human populations is around 105 males per 100 females, though it can range from 103 to 107. At present, at least seven countries, including the world’s two largest populations, have skewed sex ratios at birth reflecting son preference pregnancy interventions (Figure 1).

China and India have skewed sex ratios at birth of 113 and 110 males per 100 females, respectively. High sex ratios at birth are also observed in Azerbaijan (113), Viet Nam (112), Armenia (111), Pakistan (109), and Albania (109). In contrast, for the period 1970-1975 when pregnancy interventions by couples had not yet become widespread, the sex ratios at birth for those seven countries were within the expected normal range.

Also in some countries, the female sex ratio imbalance continues throughout women’s lives. For example, India, Pakistan, and China, which together account for nearly 40 percent of the world’s population, the sex ratios for their total populations are 108, 106, and 105, respectively. In contrast, the population sex ratios are 100 in Africa and Oceania, about 97 in Northern America and Latin America and the Caribbean, and 93 in Europe (Figure 2).

In terms of education, while progress has been achieved in the past several decades, girls continue to lag behind boys in elementary school education in some countries, especially in Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. For example, 78 girls in Chad and 84 girls in Pakistan are enrolled in primary school for every 100 boys.

Among young women between 15 to 24 years approximately one-quarter are expected not to finish primary school. In addition, about two-thirds of the illiterate people in the world are women.

With respect to decision making, women do not have political representation or participation levels similar to men. Worldwide the estimated percentages of women in national parliaments, local governments, and managerial positions are 26, 36, and 28 percent, respectively. Even in developed countries, such as the United States, women make up 27 percent of Congress, 30 percent of statewide elected executives, and 31 percent of state legislators.

The labor force participation of women is also considerably lower than that of men. Globally in ages 25 to 54 years, for example, 62 percent of women are in the labor force compared to 93 percent of men. Also, the majority of the employed women, or 58 percent, are in the informal economy earning comparatively low wages and lacking social protection.

In general women are employed in the lowest-paid work. Worldwide women earn about 24 percent less than men, with 700 million fewer women than men in paid employment.

Women perform at least twice as much unpaid care as men, including childcare, housework, and elder care. Unpaid care and household responsibilities often come on top of women’s paid work.

Increasing men’s participation in household tasks and caregiving would contribute to a more equitable sharing of those important domestic responsibilities. Also, governmental provision of childcare to families with young children would help both women and men combine their employment with family responsibilities.

A global comparative measure of women’s standing relative to men for regions and countries is the gender parity index. The index considers gender-based gaps across four fundamental dimensions: economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment.

The regions with the highest gender equality are Western Europe and Northern America with parity indexes of 78 and 76, respectively. In contrast, the regions with the lowest gender equality are South Asia and the Middle East and North Africa with parity indexes of 62 and 61, respectively (Figure 3).

With respect to countries, the top five countries with the highest gender equality are Iceland, Finland, Norway, New Zealand, and Sweden, with parity indexes ranging from 82 to 89. The bottom five countries with the lowest gender equality are Afghanistan, Yemen, Iraq, Pakistan, and Syria, with parity indexes between 44 to 57.

In addition to the four fundamental dimensions of the gender parity index noted above, other important areas reflecting women’s subordination include misogyny, sexual harassment, domestic abuse, intimate partner violence, and conflict-related sexual violence.

Worldwide it is estimated that 27 percent of women between ages 15 to 49 years had experienced physical or sexual violence by intimate long-term partners, often having long-term negative effects on the health of women as well as their children.

In addition, civil conflicts in countries, such as Ethiopia, Myanmar, South Sudan, and Syria, have all featured alarming reports of sexual violence against women. More recently, conflict-related sexual violence by the Russian forces in Ukraine is being reported, which has contributed to renewed attention by the international community to the sexual violence women face in conflict situations.

The sexual harassment of women is a widespread global phenomenon. Most women have experienced it, especially in public places, which are often considered the domain of men with the home being considered the place for women. The reported percentages of women having experienced some form of sexual harassment in India and Viet Nam, for example, are nearly 80 and 90 percent, respectively.

In addition to harassment, women in places such as India face risks from cultural and traditional practices, human trafficking, forced labor and domestic servitude. Moreover, the sexual harassment of women at the workplace is responsible for driving many to resign from their jobs.

Again, if men were experiencing misandry, discrimination, abusive treatment, harassment, and the subordination that women endure, they would be angry, intolerant, and no doubt turn to government officials, legislatures, courts, businesses, rights organizations, and even the streets to demand equality. Women should give serious consideration to the actions that men would take if inequalities were reversed.

With women continuing to lag behind men in rights, freedoms, and equality, the puzzling question that remains is: why aren’t more women angry?

Joseph Chamie is a consulting demographer, a former director of the United Nations Population Division and author of numerous publications on population issues, including his recent book, “Births, Deaths, Migrations and Other Important Population Matters.”

© Inter Press Service (2022) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source