STOCKHOLM, Jun 03 (IPS) – What I have most wanted to do… is to make political writing into an art.

George OrwellWarfare and misinformation are intimately connected. The 29th of May was globally observed as The Day of Communication and due to the ongoing war in Ukraine it was difficult to avoid thinking of affiliated propaganda campaigns, carried out by warring factions and far from indifferent bystanders.

I was reminded of this when I some weeks ago watched the Polish director Agnieszka Holland’s 2019 film Mr Jones, a co-production between Polish and Ukrainian media companies. In Ukrainian the film was named ???? ??????, The Price of Truth. It tells the story of Gareth Jones, an ambitious young Welsh journalist who in 1933, after gaining some fame for an exclusive interview with Adolf Hitler, was able to obtain permission to enter the Soviet Union. A privilege mostly due to the fact that Jones had served as secretary to former British prime minister Lloyd George. Jones’s intention to interview Joseph Stalin could not be realized, though he was offered an exclusive guided tour to pre-selected industries in Donbas. On his way there, Jones double-crossed his “handler”, jumped off the train in the Ukrainian countryside and became a shocked witness to the Ukrainian Holodomor, the catastrophic famine that resulted in at least 3 million deaths.

Gareth Jones documented empty villages, starving people, cannibalism and the enforced collection of grain. On his return to Britain, he struggled to get his story taken seriously and finally succeeded in having his articles published by The Manchester Guardian and New York Evening Post, thus revealing the conceit of the Soviet propaganda machine, which had hidden and covered up the enormous scope of the catastrophe and the Soviet Government’s guilt for its origin and development. The film ends by recording how Jones two years after his revelations was murdered while reporting in Inner Mongolia, betrayed by a guide clandestinely connected to the Soviet secret service.

The film Mr Jones emphasised the relevance of a misguided, or even corrupted, journalist corps, foremost among them The New York Times’ Walter Duranty, who from his privileged and pampered existence in Moscow served as a mouthpiece for Stalin’s terror regime. For his “unbiased and well-written” articles, Duranty was in 1932 awarded the U.S. prestigious Pulitzer Prize.

While watching the movie, I became somewhat bewildered by several cameos presenting George Orwell writing his Animal Farm. The film seems to indicate that Orwell met with Gareth Jones and that his Animal Farm was inspired by Jones’s work. To my knowledge Jones and Orwell never met, though this fact does not hinder the possibility of Orwell having read his articles and that the Animal Farm has had a crucial role in Ukrainian politics.

Famines and governments’ occasional efforts to cover them up is an essential feature in Orwell’s fable. It is hunger that triggers the farm-animals’ revolt. However, when their work and freedom are used to benefit the dictatorial pig Napoleon’s selfish well-being, hunger and suffering return to harass the animals. The megalomaniac Napoleon and his acolytes hide embarrassing facts from a global environment, which the mighty pig manipulates and makes business with:

- Starvation seemed to stare them in the face. It was vitally necessary to conceal this fact from the outside world. Napoleon was well aware of the bad results that might follow if the real facts of the food situation were known, and he decided to make use of Mr Whymper to spread a contrary impression.

Orwell wrote Animal Farm between November 1943 and February 1944, when Britain was in alliance with the Soviet Union against Nazi Germany. Since the Allies did not want to offend the Stalinists, the manuscript was rejected by British and American publishers. After much hesitation a small book publisher issued the novel by the end of the war in 1945. After Allied relations with the Soviet Union turned into hostilities Animal Farm became a great commercial success.

The novel’s harsh criticism of the Soviet State is obvious to everyone – it is a fable telling the story of talking and thinking farm animals who rebel against their human farmer, with a hope to end hunger and slavery and create a society where all animals are equal, free, and happy. Wistfully, the revolution is betrayed by infighting and self-interest among its leaders – the intellectual pigs. The still food producing farm is by the hard-working animals proudly declared as The Animal Farm, with its own hymns, insignia, myths and slogans, but it eventually ends up in a state of repression and violence just as bad, or even worse, as it was before. The omnipotent pig Napoleon (whose name in the French translation was changed to “Caesar”), is without doubt a caricature of Stalin, with his scared and lying acolytes, fierce watchdogs brought up by himself, show trials, political persecution, murders, Stakhanovites/Super Workers, and ethnic clensing. A nightmarish world Orwell developed further in his next novel – 1984. With its Big Brother watching your every move and where citizens are brainwashed through torture, doublethink, thought-crimes, and newspeak:

- The Ministry of Truth — Minitrue, in Newspeak… was startlingly different from any other object in sight. It was an enormous pyramidal structure of glittering white concrete, soaring up, terrace after terrace, 300 metres into the air. on its white face in elegant lettering, the three slogans of the Party: WAR IS PEACE, FREEDOM IS SLAVERY, IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH.

It was as a volunteer during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) Orwell obtained his dislike for Stalinism, loathing of Fascism, and anger over “Western indifference”:

- The most baffling thing in the Spanish war was the behaviour of the great powers. The war was actually won for Franco by the Germans and Italians, whose motives were obvious enough. The motives of France and Britain are less easy to understand. In 1936 it was clear to everyone that if Britain would only help the Spanish Government, even to the extent of a few million pounds’ worth of arms, Franco would collapse and German strategy would be severely dislocated.

In his preface to the Ukrainian edition of Animal Farm Orwell wrote that after the Stalinists had gained partial control of the Spanish Government they had begun hunting down and execute socialists with different opinions. Man-hunts which went on at the same time as the great purges in the USSR:

- It taught me how easily totalitarian propaganda can control the opinion of enlightened people in democratic countries ”the mutability of the past”. Falsification, airbrushing, rewriting history: in short, the memory hole. And so for the last ten years, I have been convinced that the destruction of the Soviet myth was essential if we wanted a revival of the socialist movement.

The English edition of Animal Farm reached refugee camps, where soldiers that had been drafted by the Soviet Army and several civilians occasionally killed themselves, rather than returning to the Soviet Union. 24-year-old Ihor Šev?enko, a refugee of Ukrainian origin was part of a movement for Ukraine’s independence. After having learned English from listening to the BBC he translated Animal Farm into Ukrainian and it was spread in handwritten copies, or read aloud, in refugee camps. In April 11, 1946, Šev?enko wrote to Orwell asking if he could publish his novel in Ukrainian. Orwell agreed to write a preface and refused any royalties.

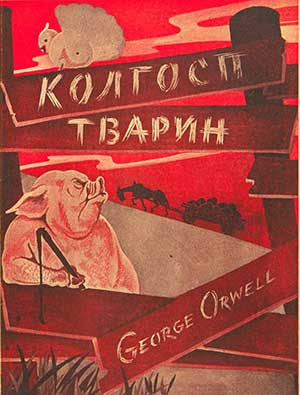

The translation was published in Munich and shipments of the book were quietly delivered to the refugee camps. Its Ukrainian title was Kolhosp Tvaryn, A Collective Farm of Animals, an obvious reference to Stalin’s forced collectivization implemented by the terror famine. However, only 2,000 copies were distributed; a truck from Munich was stopped and searched by American soldiers, and a shipment of an estimated 1,500 to 5,000 copies was seized and handed over to Soviet repatriation authorities and destroyed.

It was first some years later the Ukrainian translation of Animal Farm became appreciated by Western covert operation organizations and was secretley distributed into Ukraine as anti-Soviet propaganda. It is still generally read and in high regard within an Ukraine liberated from Soviet/Russian repression.

If the novel is read today it is easy to discern affinities between the dictatorial pig Napoleon and the current Russian warlord Vladimir Putin. Like Napoleon, Putin appears to want to turn the clock back to an imagined Russian imperial heyday, or as in the title of Masha Gessen’s study of Putin’s Russia, The Future is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia. In Animal Farm Napoleon starts to walk upright on his hind-legs, dresses in human festive clothes and declares that the name Animal Farm has been abolished:

- Henceforward the farm was to be known as the Manor Farm – which he believed, was its correct and original name.

Sources: George Orwell – Animal Farm: A Fairy Story, Also Including in Two Appendices Orwell´s Proposed Preface and the Preface to the Ukrainian Edition. London: Penguin Classics 2004, Nineteen Eighty-Four, 1984. London: Penguin Classics 2015.

IPS UN Bureau

Follow @IPSNewsUNBureau

Follow IPS News UN Bureau on Instagram

© Inter Press Service (2022) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source