WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange is making a last-ditch attempt to prevent his extradition to the United States to face criminal charges over espionage and the publication of classified information.

WikiLeaks caused a diplomatic storm after it published a huge cache of secret military files in 2010 and 2011. Washington wants to try him for the leaks that it says damaged its national security.

Here is what we know about Assange and his legal battle:

What is the trial about?

Two senior judges will hear arguments from Assange’s legal team over two days starting on Tuesday.

A UK High Court in 2021 ordered Assange’s extradition, which was upheld by the Supreme Court a year later. Former home secretary Priti Patel cleared Assange’s extradition order in April 2022.

The Australian-born Assange, who has been in prison since 2019, wants a review of former home secretary’s extradition order and to challenge the 2021 court order in the two-day hearing.

What is WikiLeaks?

In 2006, Assange launched WikiLeaks, an online platform where people can anonymously submit classified leaks such as documents and videos.

In April 2010, WikiLeaks released footage showing a US Apache helicopter attack which killed a dozen people, including two Reuters journalists, in the Iraqi capital, Baghdad. This caused the platform to gain prominence.

Also in 2010, it released more than 90,000 classified US military documents on the Afghanistan war, and almost 400,000 secret US files on the Iraq war. The leaks represented the largest security breaches of their kind in US military history.

WikiLeaks also released 250,000 secret diplomatic cables from US embassies around the world, with some of the information published by newspapers such as The New York Times and Britain’s The Guardian.

US politicians and military officials, angered by the leaks, argued the unauthorised publication of information put lives at risk.

In 2013, Chelsea Manning, a former army intelligence analyst, was sentenced for leaking thousands of secret messages to WikiLeaks. She served seven years in a military prison before being released on an order of President Barack Obama.

What is Assange charged with?

Assange has been indicted in the US on 18 charges over the publication of hundreds of thousands of classified documents in 2010 by WikiLeaks. Seventeen of these counts are for espionage while one is for computer misuse.

US lawyers say Assange is guilty of conspiring with Manning and attempting to hack into a Pentagon computer.

The prosecution against Assange is made under the 1917 Espionage Act, which has never before been used for publishing classified information.

Supporters of Assange argue he should be protected under the press freedoms granted by the First Amendment to the US Constitution and he had acted as a journalist to expose US military wrongdoing. Amnesty has released a statement appealing to the US authorities to drop the charges, deeming the government’s pursuit of Assange a “full-scale assault on the right to freedom of expression”.

“Julian has been indicted for receiving, possessing and communicating information to the public of evidence of war crimes committed by the US government,” Assange’s wife Stella said. “Reporting a crime is never a crime.”

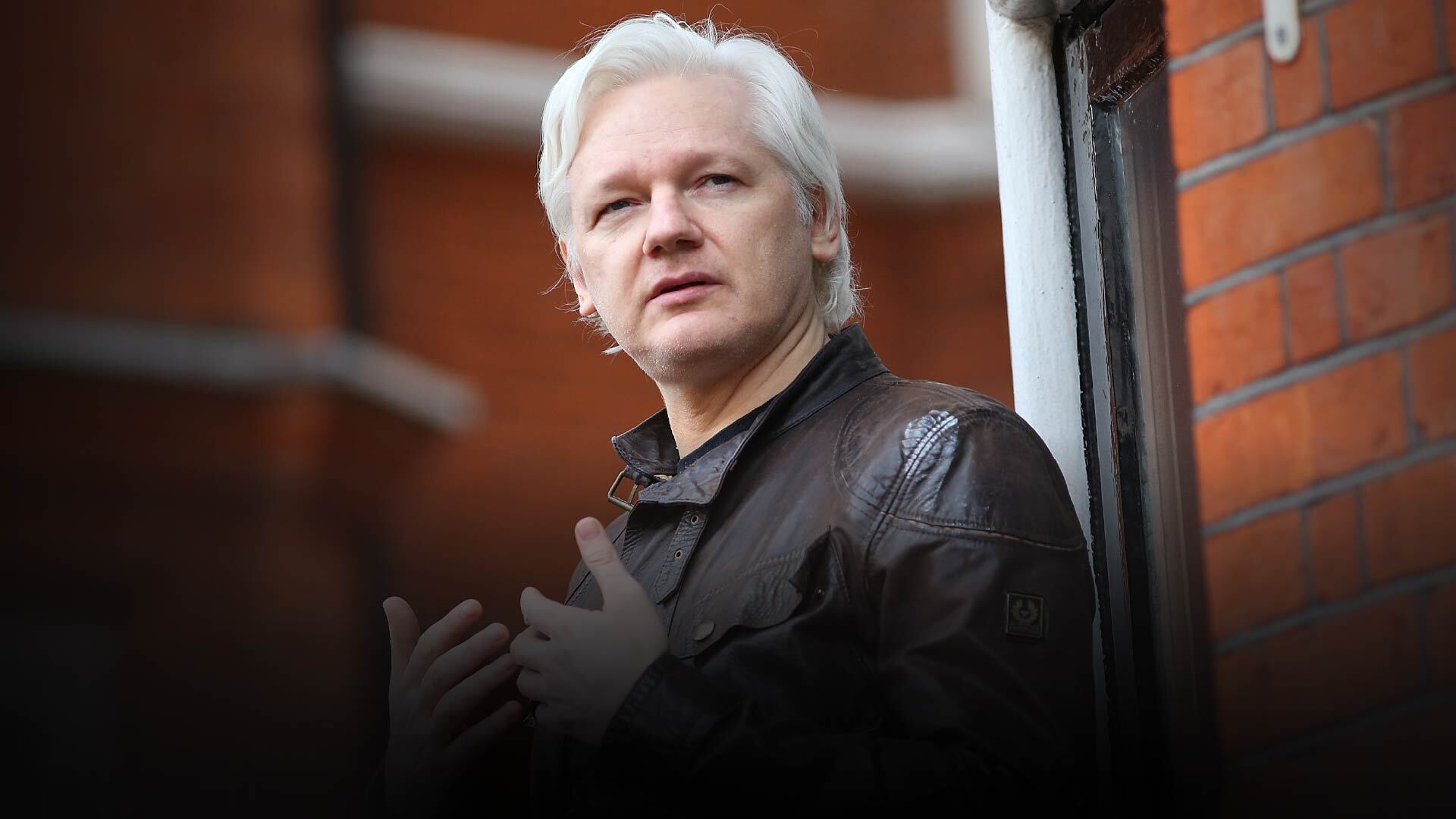

Who is Julian Assange?

Assange, now 52, was born Townsville, Australia, in July 1971.

Assange is married to Stella Assange, a lawyer who met him in 2011 when she was hired as part of his legal team.

Stella, originally called Sara Gonzalez Devant, changed her name to Stella Moris in 2012 to protect herself and her family while working with Assange.

“His life is at risk every single day he stays in prison, and if he’s extradited, he will die,” Stella has said.

Assange’s wife has been very vocal in defence of her husband. The couple has two children and married in March 2022.

Arrest and Assange’s legal battle

While the US only officially unsealed criminal charges against Assange in 2019, his legal battle spans 13 years.

On November 18, 2010, a Swedish court ordered Assange’s arrest over rape allegations made by two female Swedish WikiLeaks volunteers. Assange denied the allegations and claimed the Swedish case was a pretext to extradite him, or hand him over, to the US to face charges over the WikiLeaks releases.

In December 2010, Assange was arrested in the UK on a European Arrest Warrant but was released on bail.

London’s Westminster Magistrates Court in 2011 ordered Assange to be extradited to Sweden, a decision he appealed. In 2012, his final appeal was rejected by the UK Supreme Court, after which he sought asylum in the Ecuadorean Embassy in London.

The asylum was granted, but revoked in April 2019, after which a screaming Assange was carried out of the embassy. Throughout his asylum, UK police patrolled the embassy, saying Assange would be arrested if he left the building over his failure to surrender to bail earlier. His two children were born while he was holed up inside the embassy.

In June 2019, the US Department of Justice formally asked UK authorities to hand Assange over to the US, where he would face charges. Swedish authorities dropped the rape investigation against Assange in 2019, saying the evidence was not strong enough to bring charges, partly due to the passage of time.

The extradition hearings began in February 2020, but were adjourned after a week. In January 2021, in London, Judge Vanessa Baraitser concluded that Assange should not be sent to the US due to his frail mental health, adding there was a risk he would attempt suicide.

Besides his mental health, Assange’s physical health has also declined in prison. In October 2021, he experienced a mini-stroke. He also broke a rib coughing. His wife has said he has aged prematurely.

However, the US authorities won an appeal in December 2021 at London’s High Court against this decision, after giving a package of assurances about the conditions of Assange’s detention if convicted, including a pledge he could be transferred to Australia to serve any sentence.

What are the possible outcomes of the hearing?

If Assange and his legal team succeed, his case will be moved to a full appeal.

If he fails, his team would appeal to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) where he already has an application lodged and which could stop his extradition. However, they fear that Assange would be extradited before the European Court picks up the case.

Assange’s team plans to argue that he can not get a fair trial in the US, that a treaty between the US and UK prohibits extradition for political offences and that the crime of espionage was not meant to apply to publishers.

If Assange is extradited, his supporters say he could be held in a US high security jail and if convicted could face a 175-year prison sentence. US prosecutors have said the sentence would not be longer than 63 months.