PORTLAND, USA, Jan 16 (IPS) – Demography doesn’t care about such things as national strikes over pension retirement ages, public protests about contraception and abortion rights, sexual orientation, habits and preferences, political ideology and party affiliation, dress codes and head coverings, and religious identity, beliefs and practices.

Demography is basically about the mathematics of human populations, i.e., births, deaths, migrations, ageing, morbidity, sex ratios, mobility, size, change, growth, distribution, density, structure, composition, life expectancies, biological, social and economic characteristics, etc.

Demography is relatively straightforward, visible and equitable. For example, in every human population a person is born an infant at age zero, ages one year every twelve months, and eventually over time faces death, too often earlier rather than later unfortunately.

Between birth and death, a wide variety of demographic phenomena or transitions typically occur in human populations. Among them are surviving infancy and childhood, passing through puberty, finding a mate, having offspring, migrating to another place, falling ill or becoming disabled, and experiencing ageing.

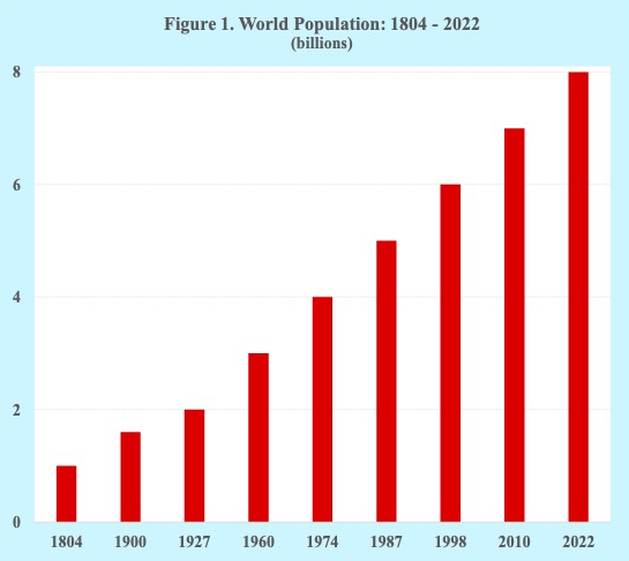

Over the many centuries of human history, the interactions of those various demographic phenomena and transitions have resulted in today’s world population of 8,000,000,000. That extraordinary number of human beings now inhabiting planet Earth is due in large part to the record-breaking rapid growth of world population during the 20th century.

World population reached the one billion milestone at the start of the 19th century in 1804. The 20th century then ushered in what turned out to be the century of rapid demographic growth. World population nearly quadrupled from 1.6 billion at the start of the 20th century to 6.1 billion by the century’s close (Figure 1).

In addition to that unprecedented rapid demographic growth, the world’s annual rate of population growth peaked at 2.3 percent in 1963. Also, by 1990 the world’s annual population increase reached a record high of 93 million.

The unprecedented growth of world population that took place during the 20th century was simply the result of births greatly outnumbering deaths with mortality rates dropping rapidly, especially during the second half of the past century.

The world’s fertility rate in the 1960s, for example, was about five births per woman and births outnumbered deaths by nearly three to one in the 1980s. Life expectancy at birth increased dramatically, increasing from about 45 years in the middle of the 20th century to about 65 years by the end of the century.

The current demographic situation for the world is different from the exceptional rates, levels and changes of the past century. For example, the growth rate of world population in 2021 was about 0.8 percent, or nearly one-third the peak level in 1963.

In addition, the annual increase of world population in 2021 was about 68 million, or about three-fourths the level in 1990. Also, the median age of the world’s population, which was about 20 years in 1970, has increased by 50 percent, reaching 30 years in 2022.

The world’s fertility rate is now about 2.3 births per woman, or about half the level 60 years ago. In addition, approximately 100 countries have a total fertility rate below the replacement level of 2.1 births per woman.

Furthermore, the fertility rates of some thirty countries in 2021 were less than 1.5 births per woman. Several of those countries had fertility rates that were approximately half or less than the replacement level, including China at 1.16, Singapore at 1.12 and South Korea at 0.81 (Chart 1).

As a result of below replacement fertility rates, the current populations of some 60 countries are expected to be smaller by 2070. The total population decline of those countries over the next 50 years is projected to be more than a half a billion. Among the countries with the largest declines in their populations are China (-340 million), Japan (-35 million), Russia (-22 million), South Korea (-16 million) and Italy (-15 million).

In addition, many countries are expected to experience substantial declines in the relative size of their populations. Many of those countries are projected to have population declines of 10 percent or more over the coming four decades. For example, the relative decline in population size is expected to be 22 percent for Japan, 21 percent for South Korea and 18 percent for Italy (Figure 2).

At the other extreme, the populations of two dozen countries, accounting for nearly 10 percent of the world’s population, are expected to more than double by 2060. Those projected population increases by 2060 include 106 percent in Afghanistan, 109 percent in Sudan, 113 percent in Uganda, 136 percent in Tanzania, 142 percent in Angola, 147 percent in Somalia, 167 percent in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and 227 percent in Niger (Figure 3).

In addition to the projected decline and growth of national populations, the age structures of countries worldwide are expected to become substantially older. Many countries have attained median ages in 2020 above 40 years, such as France at 41 years, South Korea at 43 years, Italy at 46 years and Japan at 48 years.

The median ages of populations are expected to continue rising over the coming decades. The median age for the world, for example, is expected to increase from 30 years today to close to 40 years by 2070. In some countries, including China, Italy, Japan and South Korea, the median ages of their populations by 2070 are projected to be 55 years or older.

Demographic ageing in the 21st century constitutes a major challenge for societies and economies. The consequences of the demographic realities of older population age structures and increasing human longevity are likely unavoidable.

In particular, the ageing of populations is contributing to strains on fiscal revenues and spending on pensions and healthcare for the elderly. Despite the ageing of populations and increases in human longevity, official retirement ages for government pension benefits have remained largely unchanged at comparatively low ages.

In France, for example, the official pension retirement age is 62 years, which is well below the retirement ages of many other developed countries. Despite criticisms, protests and a scheduled national strike from worker unions and leftist opponents, the French government has unveiled a pension overhaul that proposes gradually raise the retirement age to 64 years by 2030.

Also, a mounting crisis for a growing number of countries worldwide is illegal immigration. Neither governments nor international agencies have been able to come up with sensible policies and effective programs to address the mounting illegal immigration crisis.

A major factor behind the rise of illegal immigration is the large and growing supply of men, women and children in sending countries who want to migrate to another country and by any means possible, including illegal immigration. The number of people in the world wanting to migrate to another country is estimated at nearly 1.2 billion.

In conclusion, too often many choose to ignore, deny or dismiss today’s demographic realities, such as population growth and decline, demographic aging, declining fertility, rising life expectancy and increasing illegal immigration.

Rather than acknowledging, addressing and adjusting to the challenging consequences of the demographic realities of the 21st century, many are turning to protests, strikes, demonstrations, and balderdash. Demography, however, simply doesn’t care about such things.

Joseph Chamie is a consulting demographer, a former director of the United Nations Population Division and author of numerous publications on population issues, including his recent book, “Births, Deaths, Migrations and Other Important Population Matters.”

© Inter Press Service (2023) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source