Gulu, Uganda – At a market in Gulu, northern Uganda, women spread tropical fruit on plastic sheets, calling out to passing customers. The sun is blinding, and the air is thick with the chatter of bargaining shoppers.

Distant are the days when children used to sleep under the same market stall awnings, after marching grimly from the surrounding villages to this small city each night to avoid capture by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA).

Fearsome rebels commanded by Joseph Kony, the LRA dominated the region, capturing young children to serve as soldiers and sex slaves, between 1987 and 2006 before being pushed out of Uganda and into the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and the Central African Republic (CAR).

Not far from this lively market is Gulu’s High Court, which will soon play host to the trial of Thomas Kwoyelo, now in his 50s, the first LRA commander to be tried for his crimes in Uganda.

Kwoyelo was abducted as a teenager walking to school in the early years of conflict. He went on to serve in the LRA for some 20 years. Taking on the alias Latoni, the boy soldier became a senior commander and was responsible for treating wounded fighters.

He was captured during a battle in DRC in 2009. Brought home nursing a bullet wound in his stomach and without shoes, he spent the next 14 years in detention as attempts to try him dragged on.

In April 2023, more than a decade after he was jailed, the prosecution wrapped up its argument against Kwoyelo, with the defence now gearing up to make its case.

But his controversial trial has raised alarm among human rights and monitoring organisations, who say his lengthy detention has made it impossible for him to get justice.

Meanwhile, survivors of the conflict in northern Uganda assert that Kwoyelo, the first person from the armed group to be tried in the country, should not be on trial at all. They want him forgiven and allowed to come home as other LRA captives, and commanders who allegedly held higher ranks, were allowed to do so.

Rebel uprising

Kony, a former altar boy, crafted his fighting force from the remnants of another rebel group, hoping to topple President Yoweri Museveni and rule the country according to the Ten Commandments.

Clashes between the rebels and the Ugandan army killed some 10,000 people, with the LRA often turning their weapons on civilians and forcing children to become fighters.

Among them was Margret, who spoke to Al Jazeera using only her first name. Before the war, she enjoyed going to school, helping out on the family farm, and fishing in a nearby river.

In 1991, she was taken along with 15 girls from her village in an attack that killed her father and the men of their village. The new recruits were tied together with ropes and forced to carry looted goods. Margret, only 12 years old at the time, was immediately made the wife of an LRA commander.

The girl was taught to handle a weapon and transformed into a fighter. After two years with the rebels, she tried to escape, only to be taken again.

“There were terrible beatings and no one to turn to,” Margret said of her time in captivity.

These mass abductions pushed leaders from northern Uganda’s Acholi ethnic group to advocate for an amnesty policy that would allow LRA fighters who gave up their weapons to return home, free from repercussions. This policy was signed into law in 2000.

“Our children are innocent because they were forcefully conscripted into combat,” said Okello Okuna, a spokesperson for Ker Kwaro Acholi, a traditional kingdom for northern Uganda, headquartered in Gulu.

“A number of them returned home and they’re living now peacefully amidst us without any reprisal, without any reprimand [and] without any arrest,” he added.

On the local radio station Mega FM, John “Lacambel” Oryema spent the war interviewing repatriated LRA fighters and playing peace songs, urging the remaining rebels to lay down their weapons and come home again.

“I used to say, brothers, sisters, let us all unite and make sure we forgive and forget,” Oryema told Al Jazeera.

This approach ran in contrast to international interest in seeing LRA leaders tried for their crimes.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights decried Uganda’s Amnesty Act as a violation of international law, standing in the way of accountability for war crimes.

In 2003, a year after the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague was founded, Uganda referred the cases of five high-ranking LRA commanders to the court, making them the first people it indicted.

Kony, the LRA leader, has remained at large. Cases against another of his top three commanders at the ICC have been closed down, with the accused presumed dead. But in 2021, Domonic Ongwen, another boy soldier, was convicted by the court in the Hague and sentenced to 25 years in prison.

Tenuous peace

Margret gave birth to two children while in LRA captivity, and rose to the rank of sergeant. But when Uganda launched an operation against the rebels in 2004, she took her chances, fleeing into the hills with other women. In Gulu, she received amnesty and began, slowly, to rebuild her life.

Senior commanders also benefitted from the same law, renouncing rebellion, and returning home.

Charles, who like other ex-LRA recruits spoke using only his first name, was captured at a young age.

He gave few details about his time in the LRA, other than confirming he held a high rank and pointing to visible marks of conflict on his body, including an amputated leg.

“I have undergone all categories of military training,” Charles, who once hoped to become a lawyer, said bluntly. “That is how my dream was diverted and all of a sudden, I became a soldier.”

Like Margret, he received amnesty and was able to return home after 17 years of war.

Kwoyelo tried and failed to benefit from the same amnesty policy after being captured in 2009. It was originally granted by the constitutional court, but an appeal went all the way up to Uganda’s Supreme Court, which denied Kwoyelo’s request for clemency and sent his case back to the International Crimes Division (ICD) of Uganda’s High Court.

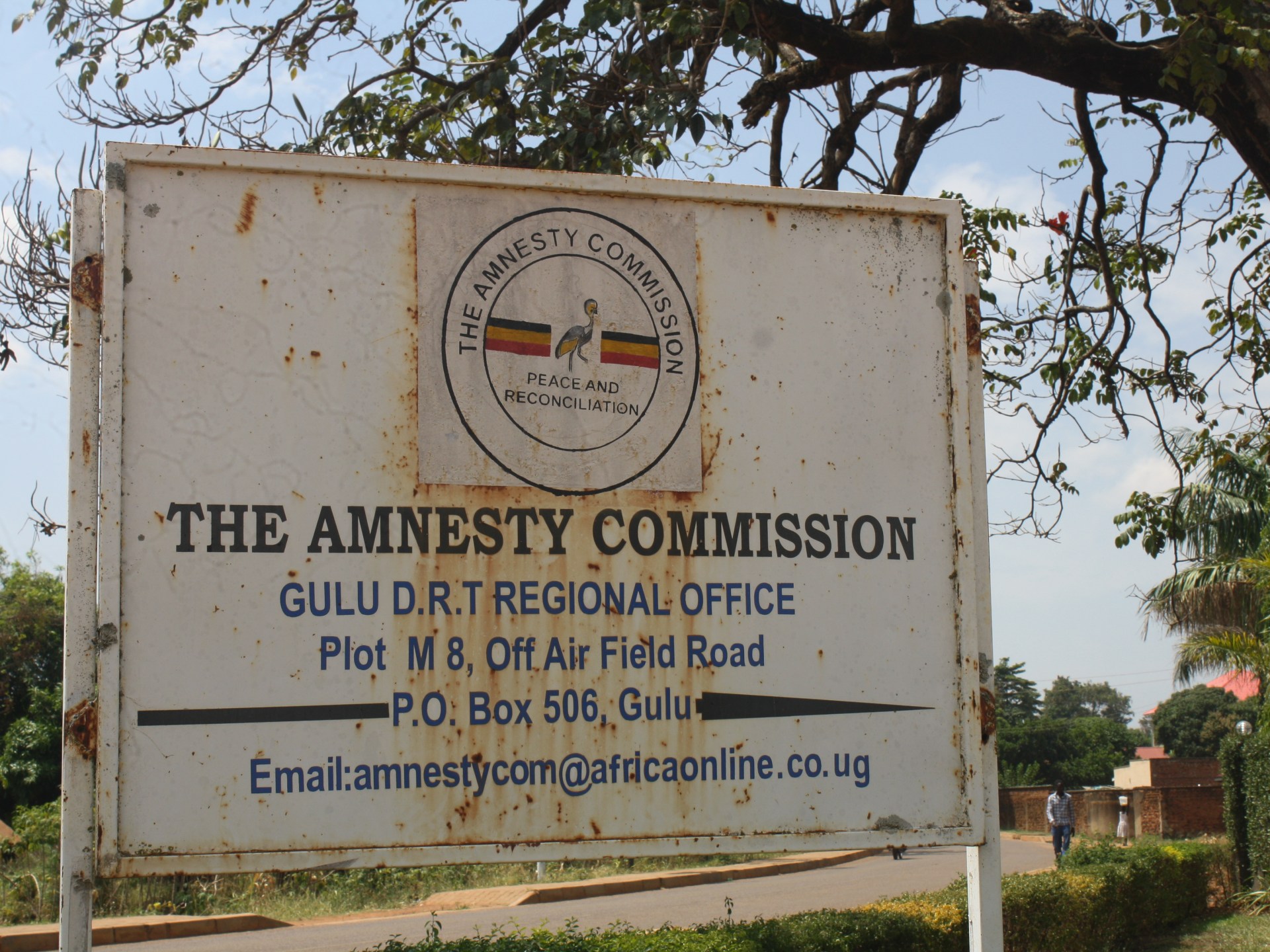

The ICD was established in 2006 as a condition of peace talks held with the LRA in Juba with the intent of trying the rebel’s top brass in Uganda. So far, Kwoyelo is the only one to face charges.

Former abductees have contended he shouldn’t be on trial at all.

“There are so many people I know that have done serious bad things that are here at home that have never been tried,” Margret told Al Jazeera. “Kwoyelo should be given amnesty so that he can be reintegrated with his family, so he has a normal life just like any of us who came back.

Agnes, who also spoke using her first name, agreed.

She was abducted by the LRA as a girl and forced to marry a commander in captivity. She recalled Kwoyelo nursing the gunshots she sustained in battle and working to gather food for the sick.

Seeing him on trial is unfair and he looked old and depressed, she told Al Jazeera.

“After all the good things that Kwoyelo did to support us … he’s not in a position to support his family or go back to his mother and his siblings,” she said.

Charles, the ex-LRA officer, was reluctant to give an opinion about a case currently before court, but eager to paint Kwoyelo – whom he referred to as his junior – in a neutral light.

“He is a normal person,” Charles said simply.

He hasn’t bothered to attend trial sessions as Agnes has, but tunes his radio to listen for news of Kwoyelo.

Others who returned from captivity or lived through the war told a different story, describing Kwoyelo as a cruel man who must answer for his crimes.

“He was a rude person and a fighter,” said Jackline, who is also being identified by only her first name. She was born in LRA captivity and accused Kwoyelo of killing her father as punishment for failing to follow orders.

Even Oryema, who spoke about forgiveness on the radio, told Al Jazeera that Kwoyelo should suffer some retribution for his crimes.

“He had very little peace in his mind,” Oryema said of a visit he made to Kwoyelo, while trying to persuade LRA recruits to return home. “He was full of revenge.”

Child soldier in court

It is amid these tensions over peace, and accountability that the Kwoyelo trial is taking place.

After 14 years, judges confirmed 78 (PDF) of the prosecution’s charges against Kwoyelo in December, including rape, murder, and the forcible recruitment of other child soldiers.

The defence plans to argue his innocence, asserting he was a victim of the war himself.

“He was abducted as a child and trained,” said Charles Dalton Opwonya, one of Kwoyelo’s lawyers. “The government failed to protect him.”

Long delays in the case – including the closure of the courts during COVID-19 – have caused funding shortages, with the court only putting on sessions when there is money to hold them, observers said.

The International Crimes Division of the High Court, where Kwoyelo is being tried, is intended to act as an equivalent to the ICC under the court’s doctrine of complementarity, which declares cases should be sent to the ICC only when the national court system is lacking.

Building that capacity is difficult and the wait is particularly hard on victims, who have spent more than a decade in limbo.

“People are tired. People are fatigued. People are anxious. People are even giving up,” said Henry Komakech Kilama. He acts as a lawyer for the victims, in a position modelled after the ICC.

The next session in Kwoyelo’s case is expected to take place on February 19, and lawyers like Kilama hope the case will be wrapped up before the end of the year.

But prior postponements have also raised concerns from human rights experts, who worry about the accused as much as his alleged victims.

“If you look at it objectively, justice delayed is justice denied. When you put someone on trial for over a decade, whatever the outcome of that trial is, it doesn’t [have] meaning,” said Irene Anying, director of Avocats Sans Frontières in Uganda, which has monitored the trial since it began.

In a January statement, Human Rights Watch also urged Uganda to bring the trial to a speedy conclusion.

Hunting Kony

With the defence now preparing its arguments in the Kwoyelo case in Uganda, the ICC has simultaneously moved forward with a separate confirmation of charges against Kony in absentia in the Hague.

“It brings confidence to the victims who have been waiting for justice, which Joseph Kony has evaded for over 18 years,” Maria Kamara, an outreach coordinator for the ICC, said from the Ugandan capital of Kampala.

Karim Khan, the ICC prosecutor, has also asserted that confirming the charges against Kony will make it easier and quicker to hold a trial in the Hague should he be caught.

The United States Department of State has offered a five million dollar reward for information that might lead to Kony’s arrest. But past attempts to hunt him down have failed.

The administration of Barack Obama funnelled eight million dollars into efforts to capture Kony between 2011 and 2017, providing logistical support to Ugandan troops, before Donald Trump shut down the mission shortly after entering office.

The LRA is now weakened and divided, expected to number about 100 to 2,000 soldiers, hiding out in jungles between the DRC and the CAR, struggling to survive.

Starting over

In Gulu, and across northern Uganda, life in once war-torn areas continues.

Coming back from the LRA was difficult, Margret said. Most of her family had died and she was not sure how to make a life for herself.

“There [was] no one to go to, no source of livelihood or income whatsoever,” she told Al Jazeera.

Despite receiving amnesty, many former LRA members face discrimination.

Margret has since joined support groups comprising other women who survived LRA captivity, but she said it is difficult to make enough money to send her children to school.

Charles also scrapes by operating a village savings organisation whose membership includes former rebels and civilians, in the hopes of fighting stigma and poverty at once.

Uganda’s parliament passed a transitional justice policy to support survivors of the war in 2019, but has yet to implement its key tenets.

Kilima, the victims’ lawyer, hoped that both a court process and more traditional methods could help bring permanent peace and stability to Uganda.

“We must look for more than one solution – not the ICC alone, not amnesty alone, not transitional justice alone,” he said. “We must look at different options. Everyone must try to contribute to the dialogue about peace.”

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source