Peruvian democracy has continued to deteriorate more than a year after the removal of former President Pedro Castillo, according to a recent report from the Washington-based nonprofit Freedom House.

The report — released this month — traced the lingering effects of a government crackdown on protesters, as well as efforts to interfere with judicial independence and other oversight bodies.

The result was that Peru slumped from a rating of “free” in 2022 to “partly free” in 2023 and 2024, as Freedom House noted declining democratic protections for the freedom of assembly and eroding safeguards against corruption.

“All these regulatory bodies and independent branches of government used to have the possibility of opposing decisions by Congress, and now that possibility is really attenuated,” said Will Freeman, the author of the report and a fellow for Latin America Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.

He added that Peru saw the fourth-largest drop in its Freedom House score of any country in the world.

“It’s all producing a situation where it’s very possible that, by the next elections in 2026, there will be no institutions that are not under the thumb of Congress.”

Harsh crackdown

While issues such as corruption and government repression are not new to Peruvian politics, experts have said they worsened after former President Castillo was impeached and arrested in December 2022.

A left-wing teacher from the country’s largely Indigenous countryside, Castillo had been facing his third impeachment proceeding at the time, led by an opposition-controlled Congress. Two prior impeachment attempts had been unsuccessful.

But on the day he was expected to appear before Congress, Castillo instead issued a televised address, in which he announced plans to dissolve Congress and rule by decree — moves widely viewed as illegal.

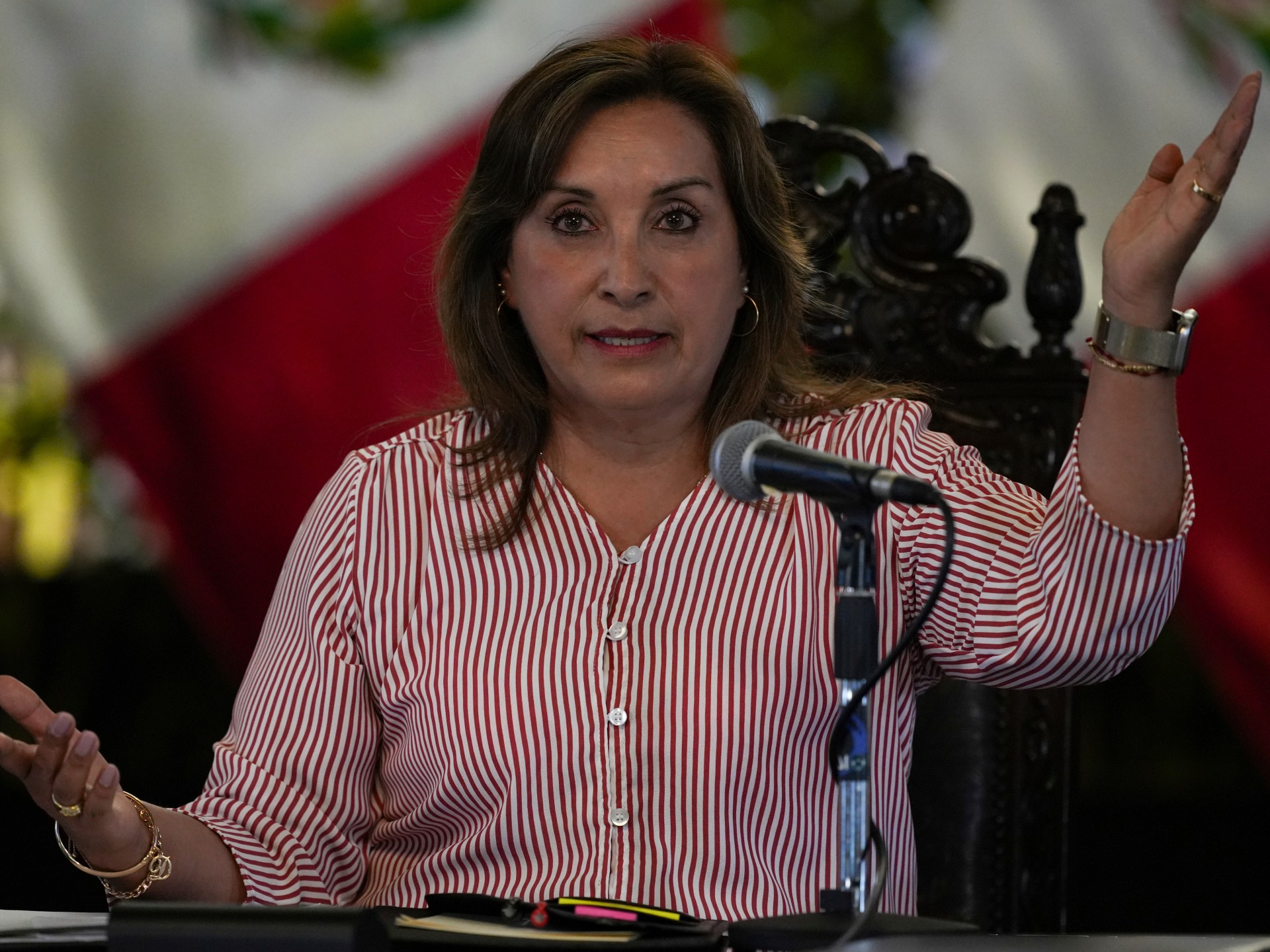

The announcement galvanised support for his impeachment, which was carried out the same day. His former vice president, Dina Boluarte, was quickly sworn in to run the government for the remainder of his term.

But the political upheaval prompted confusion and protests across Peru. Castillo’s supporters argued that he had been targeted by a hostile legislature that launched multiple investigations to stymie his administration. Many took to the streets, blocking roadways to push for government reform and Castillo’s release.

New elections became a key demand. In the immediate aftermath of Castillo’s arrest, public opinion polls suggested that more than 80 percent of Peruvians supported new elections, for both Congress and the executive branch.

Boluarte initially said she would push Congress to fast-track a vote. But Congress, with an approval rating of less than 10 percent, rejected such efforts on at least five occasions. Boluarte has also reversed course, saying she would remain in office until the end of her term.

“The conversation is over,” Boluarte said in June of last year. “We will continue until 2026.”

A January poll found that she had an approval rating of just 8 percent, one of the lowest of any political leader in the world.

Boluarte has also taken a hardline approach to the protesters, portraying them as “terrorists”. Government forces killed at least 49 civilians during confrontations with protesters, including bystanders, according to the Peruvian attorney general’s office.

Human rights organisations like Amnesty International compared the deaths to extrajudicial killings and documented reports of human rights abuses. Rural and largely Indigenous parts of the country suffered a disproportionate share of the violence.

Boluarte said that any abuses would be investigated, but advocates say there are few signs of accountability more than a year later.

“There’s been no convictions,” said Freeman. “It doesn’t seem like the investigations have advanced much.”

While antigovernment protests flared up again in July 2023, they have largely fallen off in the time since.

The Freedom House report notes that, while some groups continue to hold smaller protests against the government, “the presence of heavily armed riot police at demonstrations since has exercised a chilling effect on civil society”.

“What was new was the scale of this crackdown. It’s hard to say how much that’s contributing to the demobilisation of society, or if it’s a sense of apathy and belief that there’s no way to dislodge the status quo,” said Freeman.

Diminishing transparency

The flagging protest movement has coincided with congressional moves to diminish transparency and shore up the interests of legislators, Freeman said.

In February, for instance, a body known as the Constitutional Tribunal, whose members are appointed by Congress, moved to weaken judicial oversight of the legislature’s actions.

The Constitutional Tribunal also approved a resolution allowing Congress to put officials from Peru’s electoral court, the JNE, on trial before the legislature.

In its latest report, Freedom House warned that the resolution would open the court up to greater political pressure. Right-wing lawmakers have long castigated the JNE, pushing unsubstantiated claims that the court perpetuated fraud during the 2021 election, which saw Castillo — a political outsider — voted into office.

The election, however, was given a clean bill of health by international observers. Nevertheless, far-right actors have continued to threaten the JNE. For instance, in 2023, the Inter-American Human Rights Court granted protective measures to the JNE’s President Jorge Luis Salas Arenas, after he received a series of death threats.

“The international missions recognized the results of the polls,” Miguel Jugo, deputy secretary of the National Human Rights Coordinator (CNDDHH) in Peru, told Al Jazeera. “Dr Salas Arenas ruled against all of the requests by the fraudsters [making claims of fraud], and for this they have never forgiven him.”

In December, Congress also passed legislation making it more difficult to form new parties and diluting the influence of regional movements.

The Freedom House report also found that efforts to crack down on corruption have suffered under the current administration.

In September and October, Attorney General Patricia Benavides removed lead prosecutors from one of the country’s largest anticorruption cases, involving the Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht.

The Odebrecht scandal had already rocked governments throughout the region, with allegations against senior political figures in multiple countries.

Benavides also fired prosecutors in a case involving her sister, a judge who was under suspicion of giving favourable treatment to narcotics traffickers. Benavides was also accused of influence peddling and interfering in efforts to root out corruption in the judiciary.

Those allegations led to Benavides herself being suspended from office in December 2023. She was replaced by an interim attorney general who reinstated some of the prosecutors she had removed.

Civil society groups warn this trend of alleged corruption will continue, so long as the government continues to erode institutional safeguards.

When asked if he was concerned whether the 2026 elections will be free and fair, Jugo expressed caution.

“Yes,” he told Al Jazeera, “to the extent that there is an interest on the part of this alliance between Congress and the executive to take over the entire electoral system.”

“The current Congress, which has an approval rating of 6 percent, has modified 53 articles of the Constitution, which represents 30 percent of [the document],” Jugo added.

He explained that the constitutional changes are likely setting the groundwork for the status quo to hold onto power. “From there, it would not be strange to stay by hook or crook.”