NOUAKCHOTT, Mauritania, Jul 12 (IPS) – Deep in the heart of Southeastern Mauritania lies the district and town of Bassikounou, nestled on the border with neighboring Mali, over 1,200 kilometers from the capital city of Nouakchott.

The border between the two countries is barely visible, but the communities on either side remain tightly knit through their shared family ties, trading relationships and religious traditions.

The vast grasslands of Bassikounou have long provided nourishment for herds of livestock, yet in recent years, the region has experienced a decline in rainfall and pasture which has made life more challenging for communities and their animals.

In addition to the strains caused by a changing climate, in 2022, Mauritania experienced an influx of new refugees, including Mauritanian returnees from Mali due to the deteriorating security situation.

By the end of last year, almost 83 000 refugees resided in the Mbera camp in Bassikounou and over 8,000 in small villages outside the camp.

This influx of refugees with their livestock increased pressure on the pastures and water sources; and led to greater conflict and competition between communities for access to water and grazing fields.

On top of this, returning pastoralist herds of livestock are estimated at 800,000; further exacerbating the scarcity of resources, and raising concerns about tensions with the host population over water access.

Cohesion and economic empowerment

As part of my new role as Resident Coordinator in Mauritania, I visited Bassikounou district in January 2023 to see how the UN country team on the ground was utilizing the Secretary-General’s Peacebuilding Fund (PBF) to foster conflict prevention, promote social cohesion and tackle the devastating effects of climate change among the host communities, Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) and refugees.

The PBF’s investment in Mauritania date back to 2018 when FAO, UNDP, UNICEF and OHCHR collaborated to implement a pioneering project aimed at managing scarce natural resources, enhancing economic development, and supporting village committees to resolving conflicts.

Although the project has ended, lasting effects can still be observed. For example, the local radio station which was set up with the support of the PBF is now managed by the local and has become a vital tool in promoting social harmony between host communities and refugees.

As the head of the coordination cell of the Hodh El Charugui told me during the visit, “the radio is a jewel, through its broadcasting and radio talk shows, it allowed to reinforce social cohesion and peaceful coexistence between refugees and host communities” including young people and women.

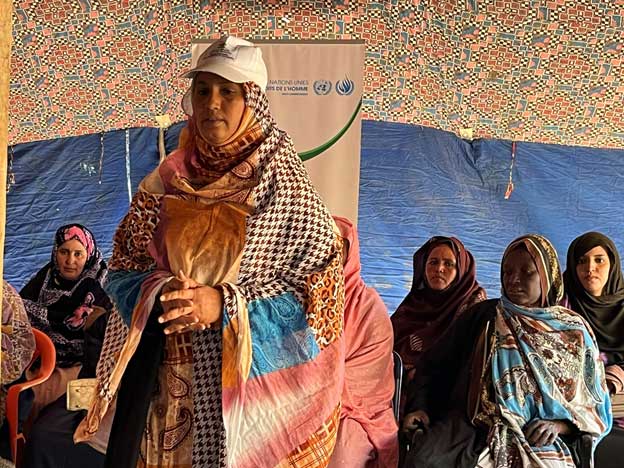

During my visit, I also had the privilege of meeting inspiring women and young girls who shared their journeys towards greater economic empowerment. The Bassikounou women’s network, which was supported by PBF’s first project in the region, consists of 49 gender focal points, village committees and 20 women’s associations. The network is now fully institutionalized with legal status.

The women spoke about the transformational change they brought to their communities through this network by implementing simple rules to lift structural barriers regarding women’s participation and rights.

Women play a critical role in conflict management and peacebuilding efforts in Mauritania. Credit: IOM Mauritania

Whilst in Bassikounnou I also had the honor of meeting with the Mourchidates, a group of fifty Mauritanian women religious guides, who are working to deconstruct radical rhetoric arguments used by extremist groups in Néma, and prevent violent extremism.

Through an innovative pilot initiative supported by PBF and implemented by UNOSSC and UNESCO, these women received training on how to spot warning signs of radicalization in individuals and communities and how to intervene early to prevent violence from erupting.

Building resilience to climate shocks

Investing in adaptation measures and building greater resilience to the effects of climate change is another key priority for host communities, IDPs and refugees in Bassikounou district.

Mauritania’s mostly desert territory is highly susceptible to deforestation and drought, with temperatures regularly exceeding 40°c during the dry season from September to July; which means that bushfires have become an increasingly frequent occurrence threatening refugees and host communities, their herds and livelihoods.

With thanks to support from the UN country team and investments from the PBF, communities are coming together to manage and mitigate risks of such bushfires.

During my visit to the district, I saw first-hand the achievements of the Mbera fire brigade volunteers. Founded by refugees, this all-volunteer firefighting group has extinguished over 100 bushfires since 2019 and planted thousands of trees to preserve the lives, livelihoods of the host communities and refugees and the local environment.

These interactions between refugees and host populations has led to a more inclusive, equitable and sustainable management of natural resources in Mbera. The Fire Brigade’s courage and tenacity in safeguarding lives, livelihoods and the environment has earned them the title of the Africa Regional Winner of the 2022 Nansen Refugee Award.

Elsewhere during our visit to Mbera camp and surrounding villages, we saw inspiring youth and women-led initiatives to strengthen community resilience to climate change and promote social cohesion, specifically through the regeneration of vegetation cover.

Through the planting of 20,000 seedlings cultivated on five reforestation sites, women are now able to sell vegetables produced in community fields to sustain their families, invest in small businesses, and save for joint initiatives. In addition, a youth-led start-up is piloting biogas production in Bassikounou by employing youth to provide natural gas for vulnerable families.

Towards peace and prevention

Beyond Bassikounou, the Fund has invested in cross-border initiatives to address fragility risks, including in Mauritania due to its porous borders and security threats such as trafficking and terrorism.

Between Mali and Mauritania, with PBF’s support, FAO and IOM are strengthening the conflict prevention and management capacities of cross-border communities by setting up, training and equipping 24 village committees located on the Mauritano-Malian border zone.

In a world that is often plagued by conflict and strife, the need for peacebuilding initiatives has never been greater. The Secretary-General’s Peacebuilding Fund is a unique tool that can effectively prevent conflicts from escalating and support ongoing peacebuilding efforts.

My visit to Bassikounou allowed me to see firsthand the changes and transformation on the ground supported by the PBF and jointly implemented by the UN country team and national partners and refugees communities.

From strengthening social cohesion to empowering more women and young people in conflict and natural resource management, the impact of these initiatives continues to grow.

I am more convinced than ever that we must continue to support such initiatives and invest in peacebuilding – only then can we hope to create a better future for all.

Lila Pieters Yahia is UN Resident Coordinator in Mauritania. This article was written with support from the UN Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA) and the Peacebuilding Support Office (PBSO).

Source: UN Development Coordination Office (UNDCO), New York.

IPS UN Bureau

Follow @IPSNewsUNBureau

Follow IPS News UN Bureau on Instagram

© Inter Press Service (2023) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source