Marginalising Key Populations Impacting Efforts to End HIV/AIDS Epidemic — Global Issues

BRATISLAVA, Jul 14 (IPS) – A report released this week has highlighted how continuing criminalisation and marginalisation of key populations are stymying efforts to end the global HIV/AIDS epidemic.

The report from UNAIDS, entitled ‘The Path that Ends AIDS’, says that ending AIDS is a political and financial choice, and that in countries where HIV responses have been backed up by strong policies and leadership on the issue, “extraordinary results” have been achieved.

It points to African states that have already achieved key targets aimed at stopping the spread of HIV and getting treatment to people with the virus. It also points out that a further 16 other countries, eight of them in sub-Saharan Africa which accounts for 65% of all people living with HIV, are close to doing so.

But the report also focuses on the devastating impact HIV/AIDS continues to have and how alarming rises in new infections in some places are being driven largely by a lack of HIV prevention services for marginalised and key populations and the barriers posed by punitive laws and social discrimination.

“Countries that put people and communities first in their policies and programmes are already leading the world on the journey to end AIDS by 2030,” said Winnie Byanyima, Executive Director of UNAIDS.

Experts and groups working with key populations have long warned of the effect that the stigmatisation, persecution and criminalisation of certain groups has on the AIDS epidemic.

They point to how punitive laws can stop many people from accessing vital HIV services.

Groups working with people with HIV in Uganda, which earlier this year passed anti-LGBTQI legislation widely considered to be some of the harshest of its kind ever implemented (it includes the death penalty for some offences), say service uptake has fallen dramatically.

“The law has had a very negative effect in terms of health,” a worker at the Ugandan LGBTQI community health service and advocacy organisation Icebreakers told IPS.

“Community members are threatened by violence and abuse by the public; many are afraid to go out. HIV service access points are now seen by LGBTQI community members as places where they will be arrested or attacked,” he said.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, the worker added: “This is going to affect adherence to treatment and will be bad for the spread of HIV. Some people are being turned away at service centres, including places where people go for ARV refills, because although the president has declared that treatment will continue for members of the community, there are individuals at some centres who say the law has been passed, and so they don’t need to give treatment to members of the community.”

Groups working with people with HIV in other countries where strict anti-LGBTQI laws have been introduced have also warned that criminalisation of the minority will only worsen problems with the disease.

In Russia, which has one of the world’s worst HIV/AIDS epidemics, anti-LGBTQI legislation brought in last year has effectively made outreach work illegal, potentially severely impacting HIV prevention and treatment. Widespread antipathy to the community also forces many LGBTQI people living with HIV to lie to doctors about how they acquired the disease, meaning the epidemic is not being properly treated.

A worker at one Moscow-based NGO helping people with HIV told IPS: “What this means is that the right groups in society are not being targeted , and so the epidemic in Russia is what it is today.”

Harsh legislation, conservative policies and state-tolerated stigmatisation also impact another key population – drug users.

Countries in regions where drug use is the primary or a significant driver of the epidemic, such as Eastern Europe and Central Asia and Asia and the Pacific, drug users often struggle to access harm reduction and HIV prevention services. They fear arrest at needle exchange points, attacks from a general public which often views them negatively, and prejudice and stigmatisation from workers within the healthcare system.

At the same time, in states with harsh laws targeting the LGBTQI community, drug users, sex workers or other vulnerable groups, civil society organisations helping those populations are also affected by the legislation, meaning that vital HIV prevention and treatment services they provide are hampered or halted completely.

And these problems are not confined to a handful of states. The UNAIDS report states that laws that criminalize people from key populations or their behaviours remain on statute books across much of the world. The vast majority of countries (145) still criminalize the use or possession of small amounts of drugs; 168 countries criminalize some aspect of sex work; 67 countries criminalize consensual same-sex intercourse; 20 countries criminalize transgender people; and 143 countries criminalize or otherwise prosecute HIV exposure, non-disclosure or transmission.

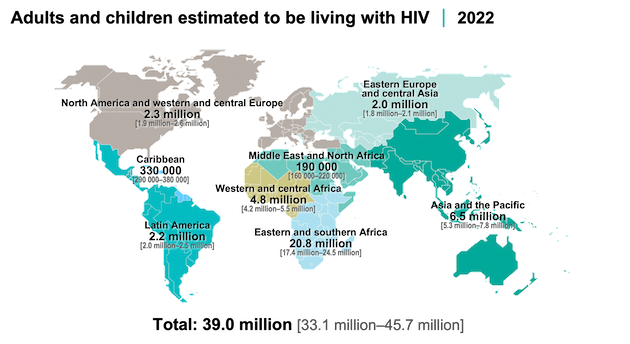

Consequently, the HIV pandemic continues to impact key populations more than the general population. In 2022, compared with adults in the general population (aged 15-49 years), HIV prevalence was 11 times higher among gay men and other men who have sex with men, four times higher among sex workers, seven times higher among people who inject drugs, and 14 times higher among transgender people.

Ann Fordham, Executive Director at the International Drug Policy Consortium, told IPS there was an “urgent need to end the criminalisation of key populations”.

“Data shows HIV prevalence among people who use drugs is seven times higher than in the general population, and this can be directly attributed to punitive drug laws which drive stigma and increase vulnerability to HIV. It is devastating that despite evidence that these policies are deeply harmful, the majority of countries still criminalise drug use or the possession of small quantities of drugs,” she said.

But it is not just minorities which are disproportionately affected by HIV.

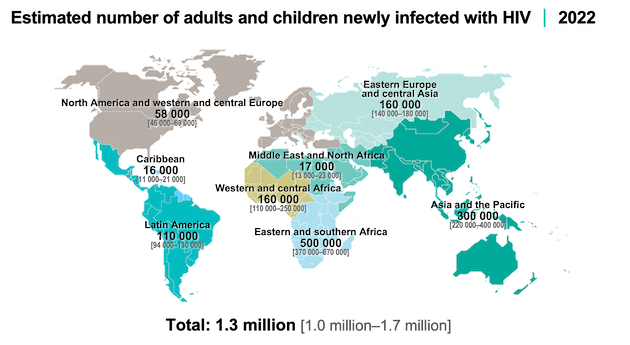

Globally, 4,000 young women and girls became infected with HIV every week in 2022, according to the report.

The problem is particularly acute in the sub-Saharan Africa region, where there is a lack of dedicated HIV prevention programmes for adolescent girls and young women and where across six high-burden countries, women exposed to physical or sexual intimate partner violence in the previous year were 3.2 times more likely to have acquired HIV recently than those who had not experienced such violence.

Research has suggested that biological, socio-economic, religious, and cultural factors are behind this disproportionately high risk of acquiring HIV. Many girls and young women in the region are economically marginalized and therefore struggle to negotiate condom use and monogamy. Meanwhile, a predominantly patriarchal culture exacerbates sexual inequalities.

“For girls and women in Africa, it is general inequalities which are driving this pandemic. It is social norms which don’t equate men and women, girls and boys, it is norms which tolerate sexual violence, where a girl is forced to have unprotected sex, and that is then dealt with quietly rather than tackling the abuser,” Byanyima said at the launch of the report.

UNAIDS officials say that promoting gender equality and confronting sexual and gender-based violence will make a difference in combatting the spread of the disease, but add that specific measures aimed at young women and girls, and not just in sub-Saharan Africa, are also important.

“ services are not designed for young women in many parts of the world – for instance, girls cannot access HIV testing or treatment without parental consent up to a certain age in some countries,” Keith Sabin, UNAIDS Senior Advisor on Epidemiology, told IPS.

“A lack of comprehensive sexual education is a tremendous barrier in many places. It would go a long way to improving the potential for good health among girls,” he added.

But while the report highlights the barriers faced by key populations, it also shows how removing them can significantly improve HIV responses.

It cites examples from countries from Africa to Asia to Latin America where evidence-based policies, scaled-up responses and focused prevention programmes have reduced new HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths, while some governments have integrated addressing stigma and discrimination into national HIV responses.

It also noted that progress in the global HIV response has been strengthened by ensuring that legal and policy frameworks enable and protect human rights, highlighting several countries’ removal of harmful laws in 2022 and 2023, including some which decriminalized same-sex sexual relations.

“Studies strongly suggest a better uptake of services among men who have sex with men (MSM) in countries where homosexuality has been decriminalised or is less criminalised. A certain policy environment can improve uptake and outcomes,” said Sabin.

The UNAIDS report calls on political leaders across the globe to seize the opportunity to end AIDS by investing in a sustainable response to HIV, including effectively tackling the barriers to prevention and services faced by key populations.

Experts agree this will be crucial to ending the global epidemic.

“We have long known that we will not end AIDS without removing these repressive laws and policies that impact key populations. Today, UNAIDS is once again sounding the alarm and calling on governments to strengthen the political will, follow the evidence and commit to removing the structural and social barriers that hamper the HIV response,” said Fordham.

IPS UN Bureau Report

Follow @IPSNewsUNBureau

Follow IPS News UN Bureau on Instagram

© Inter Press Service (2023) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source