Why is Pakistan’s PTI fighting for reserved seats in parliament? | Politics News

Islamabad, Pakistan — It is the latest setback for former Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party.

On Monday, the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) declared that the PTI-backed Sunni Ittehad Council (SIC) could not claim allocated reserved seats in the national and provincial assemblies.

PTI, unable to contest recent elections due to a ban on their electoral symbol, instructed its candidates to join the right-wing fringe religious party in order to extend their numerical strength in the National Assembly.

In its 22-page judgment issued on Monday, the five-member electoral body decided 4-1 that the SIC failed to submit a party list for reserved candidates before the ECP’s deadline of February 22, two weeks after the February 8 election.

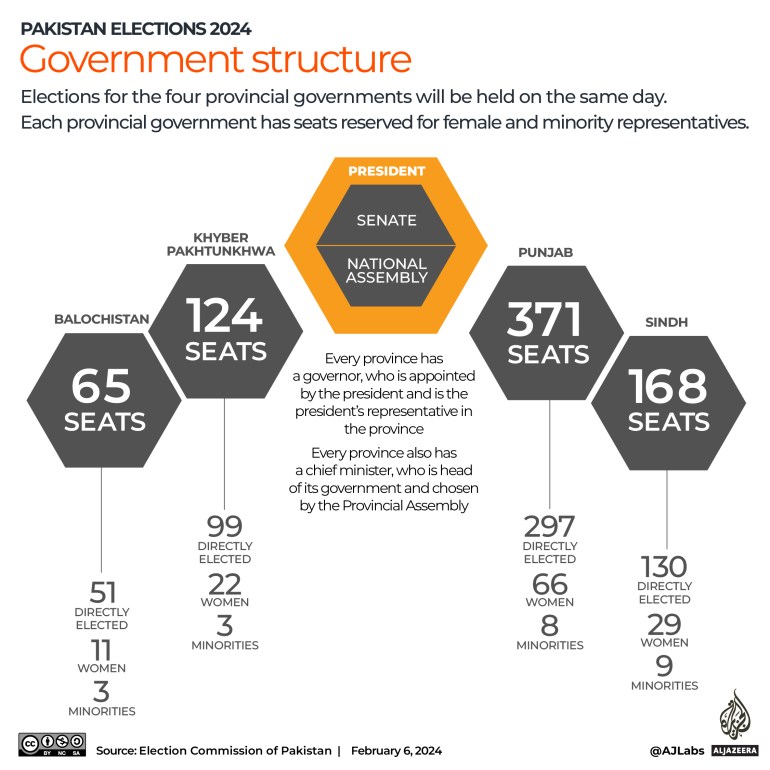

Pakistan’s National Assembly has a total of 70 reserved seats which are distributed among parties based upon their performance in the general elections. Similarly, the four provincial assemblies have a combined total of 149 reserved seats that are similarly distributed.

A majority of these reserved seats have already been allocated — around 77 remain vacant, for now.

PTI has criticised the ECP judgement, calling it an attack on democracy.

“This is the last assault on the heart of democracy,” Senator Ali Zafar of PTI, and a senior party lawyer said during a speech in the Senate, the upper house of the assembly on Monday after the decision was announced.

The ECP’s decision opens the door for a prolonged legal battle, as PTI has announced it will challenge the decision in higher courts.

However, if the party fails to overturn it, it could further dent its position in the lower house of parliament, potentially allowing the ruling coalition to gain a two-thirds majority in the 336-member National Assembly.

What are reserved seats — and why do they matter?

Pakistan’s general elections for the National Assembly take place on 266 seats. But there are an additional 70 reserved seats (60 for women and 10 for minorities) which give the body a total size of 336 seats.

To achieve a simple majority to form a government, a total of 169 seats is required. However, a two-thirds majority — or 224 votes — is necessary to make any constitutional amendments.

Reserved seats are allocated only to political parties that win seats in the National Assembly, and the distribution is done based on their proportional representation after the general elections. Similarly, reserved seats are allocated in provincial assemblies based on the parties’ proportionate performances.

According to regulations, any political party contesting the polls must submit a list of their nominations for reserved seats prior to elections, as per the schedule given by the ECP. However, after the polls, if a party has over-performed and needs to submit additional names for reserved candidates, it has two weeks to do so.

Independents have three days after their win announcement to declare their affiliation with a party in the assembly.

The party they join gets a boost in the number of reserved seats it gets, commensurate with the number of independents that join it.

In the National Assembly, the ECP has already allocated at least 40 out of 60 seats to different political parties for their reserved quota for women. Similarly, seven out of 10 seats reserved for the minorities quota have already been allocated in the lower house of the parliament. The rest are currently vacant.

What happened in the current elections?

Forced to contest the recent general elections on February 8 without its party symbol – the cricket bat – due to violating election rules, PTI fielded candidates as independents.

Despite facing a nationwide crackdown for nearly two years, with its leader, former Prime Minister Imran Khan, imprisoned since August last year, and its candidates unable to campaign freely, PTI still emerged as the single largest bloc, with its candidates winning 93 seats.

While the party claimed widespread rigging across the country and alleged a “stolen mandate”, its rivals, Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PMLN) and Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), managed to cobble together a ruling alliance, with 75 and 54 seats respectively, in coalition with other smaller parties.

Even though they won the most seats, the PTI leadership, under orders from Imran Khan, decided not to form a government with any of the major parties and instead joined hands with a fringe, right-wing religious party, the SIC, to claim reserved seats.

Complicating matters further was the fact that the SIC, despite being a registered political party, did not contest the general elections. Its leader, Sahibzada Hamid Raza, chose to contest independently, winning his seat from Faisalabad city in Punjab province.

What does the ECP verdict say?

In its verdict, the ECP stated that the SIC was not entitled to claim the quota for reserved seats due to a “violation of a mandatory provision of submitting a party list for reserved seats, which is a legal requirement”.

It also said that the currently vacant seats in the national assembly — 23 — “will not” remain vacant and will be distributed among other parties based on the elected seats they won.

The commission criticised the SIC by reminding them that they were given a specific timeframe to submit a list of nominations, which the party did not.

“Every political party, while making any decision regarding crucial steps concerning matters of the political party required under law, should be aware of the potential consequences they may face in the future,” the ECP wrote.

What are the consequences of the ECP decision?

On March 3, Shehbaz Sharif of the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PMLN) was elected the country’s new prime minister by the National Assembly, securing 201 votes. Omar Ayub Khan, the PTI leader backed by the SIC, managed to secure 92 votes.

The biggest beneficiary of the ECP decision will be Sharif’s PMLN, along with the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) and the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), which won the most number of seats in the general elections, with 75, 54 and 17 respectively.

In case PTI’s legal challenge fails to bring them any relief, it is a certainty that the ruling coalition will cross the magic figure of 224, which is required to achieve a two-thirds majority in the National Assembly.

However, if PTI manages to get the ECP decision reversed, it can expect to get 23 further seats in the National Assembly, in addition to extra seats in other provincial assemblies where they have done well. That might limit the governing coalition to just below the two-thirds mark.

What does the legal fraternity think, and what’s next?

The ECP decision has been widely criticised by lawyers, with many calling the order a “farce” or even “unconstitutional”.

Constitutional expert Asad Rahim says the ECP verdict aligns with its previous decisions that, he alleged, have disenfranchised the people of Pakistan.

“There are precedents expressly barring the minor technicalities on the basis of which the ECP barred the largest party,” the Lahore-based lawyer told Al Jazeera. “However, an even greater subversion of the democratic mandate is its division of the remaining seats among the smaller parties.”

Another legal expert, Rida Hosain, also questioned the decision to distribute the unallocated seats to other, smaller parties. She argued that no legal or constitutional provision permitted this “absurd” distribution.

“The entire framework of the Constitution and law dictates that a political party should receive reserved seats through a system of proportional representation. It is entirely undemocratic for other political parties to get a share of reserved seats beyond their proportional strength of general seats in the National Assembly,” Hosain told Al Jazeera.

Islamabad-based lawyer Salaar Khan also noted that the ECP decision lacks any “convincing justification” for allocating the unallocated seats to other parties.

“However, the impact may well be granting the coalition government a full two-thirds majority in the National Assembly,” he told Al Jazeera.

On the other hand, lawyer Mian Dawood argued that the SIC was clearly at fault for failing to submit their list within the deadline.

“This is the first instance where a political party like the SIC has not submitted its list for reserved seats as required by law, yet now demands them on grounds of morality and the law of necessity,” Dawood told Al Jazeera.

Abdul Moiz Jaferii, a constitutional expert and lawyer, viewed the ECP verdict as another “technical knockout” suffered by PTI.

“The PTI perhaps themselves opened the door to this by not standing their ground with the ECP regarding their own reserved seat lists and maintaining that they are still a political party, albeit without a symbol,” he told Al Jazeera.

Lawyers also expressed pessimism regarding PTI receiving any favourable verdict from the superior courts.

“The PTI seems to have decided to challenge the decision before the Supreme Court, and the Supreme Court’s narrow interpretation of election laws is, of course, what landed the PTI here to begin with,” lawyer Khan said, referring to the Supreme Court verdict in January this year upholding the ECP decision to strip the party of its cricket bat symbol.

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source