Trump tariffs and China: Businesses brace for impact

China correspondent

A hiss and puff of compressed air shapes the smooth leather, bringing to life an all-American cowboy boot in a factory on China’s eastern coast.

Then comes another one as the assembly line continues, the sounds of sewing, stitching, cutting and soldering echoing off the high ceilings.

“We used to sell around a million pairs of boots a year,” says the 45-year-old sales manager, Mr Peng, who did not wish to reveal his first name.

That is, until Donald Trump came along.

A slew of tariffs in his first presidential term triggered a trade war between the world’s two largest economies. Six years on, Chinese businesses are bracing themselves for a sequel now that he is back in the White House.

“What direction should we take in the future?” Mr Peng asks, uncertain of what Trump 2.0 means for him, his colleagues – and China.

A battle looms

For Western markets that are increasingly wary of Beijing’s ambitions, trade has become a powerful bargaining chip – especially as a sluggish Chinese economy relies ever more on exports. Trump returned on a campaign promise that included crushing tariffs against Chinese-made goods, and has since threatened a 10% levy that is expected to take effect on 1 February.

He has also ordered a review of US-China trade – which buys Beijing time and Washington, negotiating room. And for now, harsher rhetoric (and higher tariffs) seem to be directed against US allies such as Canada and Mexico.

Trump may have pressed pause on the looming battle with Beijing. But many believe it’s still coming. It’s hard to find an exact figure on how many businesses are fleeing China, but major firms such as Nike, Adidas and Puma have already relocated to Vietnam. Chinese businesses too have been moving, reshaping supply chains, although Beijing remains a key player.

Mr Peng says his boss, who owns the factory, has considered moving production to South East Asia, along with many of their competitors.

It would save the firm, but they would lose their workforce. Most of the staff are from the nearby city of Nantong and have worked here for more than 20 years.

Mr Peng, whose wife died when their son was young, says the factory has been his family: “Our boss is determined not to abandon these employees.”

Xiqing Wang/ BBC

Xiqing Wang/ BBCHe is aware of the geopolitics at play, but he says he and his workers are just trying to make a living. They are still reeling from the impact of 2019, when a fourth round of Trump tariffs – 15% – hit Chinese-made consumer goods, such as clothes and shoes.

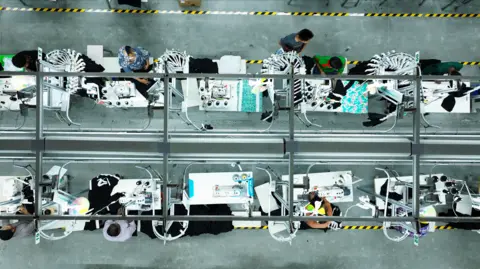

Orders have since dwindled and staff numbers, once more than 500, have dropped to just over 200. The evidence is in the empty work stations, as Mr Peng shows us around.

All around him, workers are cutting the leather into the right shape to hand it to the machinist. They have to be precise because mistakes will ruin the expensive leather, most of which has been imported from the US.

The factory is trying to keep costs low as some of their American buyers are already considering moving business away from China and the threat of tariffs.

But that would mean losing skilled workers: it can take up to a week to make one pair of boots, from flattening the leather to giving the finished boots a final polish and packing them for export.

This is what turned China into the world’s top manufacturer – labour-intensive production which is also cheap when it’s scaled up and supported by an unrivalled supply chain. And this has been years in the making.

“It was once a constant cycle of inspecting goods and shipping them out – I felt fulfilled,” says Mr Peng, who has worked here since 2015. “But orders have decreased, which makes me feel quite lost and anxious.”

Once crafted to conquer the Wild West, these cowboy boots have been made here for more than a decade. And this is a familiar story in the south of Jiangsu province, a manfucaturing hub along the Yangtze River that produces just about everything, from textiles to electric vehicles.

Xiqing Wang/ BBC

Xiqing Wang/ BBCThese are among the hundreds of billions of dollars worth of goods that China ships to the United States every year – a number that steadily ballooned as Washington became its biggest trading partner.

That status slipped under Trump. But it was not restored under his successor Joe Biden, who kept most Trump-era tariffs in place, as ties with Beijing frayed.

In fact, the European Union too has imposed tariffs on electric vehicle imports, accusing China of making too much, often with the support of state subsidies. Trump has echoed this – that China’s “unfair” trade practices disadvantage foreign comeptitors.

Beijing sees such rhetoric as Western attempts to stifle its growth, and it has repeatedly warned Washington that there will be no winners in a trade war. But it has also said it’s ready to talk and “properly handle differences”.

And President Trump, who has described tariffs as his “one big power” over China, certainly wants to talk.

It’s unclear as yet what he might want in return. During Trump’s honeymoon period with China in his first term he came to Beijing to ask for Xi’s help in meeting North Korea’s leader Kim Jong Un. This time it is believed he might need Xi’s support to make a deal with Russian President Vladimir Putin to end the war in Ukraine. He recently said that China had “a great deal of power over that situation”.

The threat of a 10% tariff is driven by the belief that China is “sending fentanyl to Mexico and Canada”. So he could demand that it do more to end that flow.

Or, given he welcomed a bidding war over TikTok, he may want to negotiate its ownership – or the prized technology that powers the app – because Beijing would need to agree to any such sale.

Xiqing Wang/BBC

Xiqing Wang/BBCWhatever the deal may be, it could help reset US-China ties. However, the absence of one could abruptly end the chance of a second honeymoon, setting up Trump and Xi for a far more confrontational relationship.

Already business sentiment is nervous: an annual survey by the American Chamber of Commerce in China showed just over half of them were concerned about the US-China relationship deteriorating further.

Trump’s seemingly softer stance on China offers offers some relief. But his hope is still that the threat of tariffs will help drive buyers away from China and move manufacturing back to the US.

Some Chinese businesses are indeed on the move – but not to America.

Moving shop

An hour outside Cambodia’s capital Phnom Penh, businessman Huang Zhaodong has built a new factory to cater to a flood of orders from US giants Walmart and Costco.

This is his second factory in Cambodia, and together they produce half a million garments a month, from shirts to underwear. Hangers carrying cotton trousers roll past us on an automated line, moving from one station to the next as the elastic waist is inserted and hemlines are finished.

Xiqing Wang/ BBC

Xiqing Wang/ BBCNow, when prospective US customers lob the first question, which he has come to expect – where is he based – Mr Huang has the right answer. Not in China.

“In the case of some Chinese firms, their customers have told them: ‘If you don’t move production overseas, I’ll cancel your orders’.”

The tariffs raise tough choices for suppliers and retailers, but it’s not always clear who will bear the brunt of the cost. Sometimes it will be the customer, Mr Huang says.

“Take Walmart as an example. I sell them clothes at $5, but they usually mark it up 3.5 times. If the cost increases due to higher tariffs, the price I sell to them might rise to $6. If they mark it up by 3.5 times, the retail price would increase.”

But usually, he says, it is the supplier. If his production line was in China, he estimates an extra 10% tariff could take an extra $800,000 (£644,000) from his earnings.

“That’s more than what I make as profit. It’s huge and we can’t afford it. If you’re making clothes in China under such tariff conditions, it’s unsustainable,” he says.

Current US tariffs on Chinese goods vary from 100% on electric vehicles to 25% on steel and aluminium. Until now, several top-selling items have been exempt, including electronics, such as TVs and iPhones.

But the 10% blanket tariff Trump is proposing could affect the price of everything that is made in China and exported to the US. That applies to a lot of things – from toys and tea cups to laptops.

Xiqing Wang/ BBC

Xiqing Wang/ BBCMr Huang says this would encourage more factories to move elsewhere. Several new workshops have sprung up around him and Chinese companies from textile production heartlands such as Shandong, Zhejiang, Jiangsu and Guangdong are moving in to make winter jackets and woollen clothing.

Around 90% of clothing factories in Cambodia are now Chinese-run or Chinese-owned, according to a report by insight and analysis group Research and Markets.

Half of the country’s foreign investment flows from China. Seventy percent of roads and bridges were built using loans Beijing dispensed, according to Chinese state media.

Many of the signs on restaurants and shops are in Chinese as well as Khmer, the local language. There’s even a ring road named Xi Jinping Boulevard in honour of the Chinese president.

Cambodia is not a lone recipient. China has invested heavily in different parts of the world under President Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative – a trade and infrastructure project that also increases Beijing’s influence.

That means China has choices.

Chinese state media claims that more than half of China’s imports and exports now come from Belt and Road countries, most of them in South East Asia.

Xiqing Wang/BBC

Xiqing Wang/BBCThis has not happened overnight, says Kenny Yao from AlixPartners, who advises Chinese firms on how to deal with tariffs.

During Trump’s first term, many Chinese firms doubted his tariff threat, he told the BBC. Now they ask if he will follow the supply chain and slap tariffs on other countries.

Just in case he does, Mr Yao says, it would be wise for Chinese businesses to look further afield: “For example, Africa or Latin America. This is more difficult, but it is good to look at areas you have not explored before.”

As America pledges to look after itself first, Beijing is doing its best to appear a stable business partner, and there is some evidence it is working.

China has edged past the US to become the prevailing choice for countries in South East Asia, according to a survey by the Iseas Yusof-Ishak think tank in Singapore.

Even though production has moved abroad, money still flows to China – 60% of the materials being made into clothes at Mr Huang’s factories in Phnom Penh come from China.

And exports are thriving, with Beijing investing more heavily in high-end manufacturing, from solar panels to artificial intelligence. Last year’s trade surplus with the world – on the back of a nearly 6% year-on-year jump in exports – was a record $992bn.

Still, Chinese businesses – in Jiangsu and Phnom Penh – are preparing themselves for an uncertain spell, if not a turbulent one.

Mr Peng hopes the US and China can have an “amicable and calm” discussion to keep the tariffs “within a reasonable range” and avoid a trade war.

“Americans still need to purchase these products,” he said, before driving off to meet new customers.

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source