The British Betrayal of an Afghan Special Police Commando Force

OPINION/EXPERT PERSPECTIVE — Two years ago, on August 28, 2021, the final British evacuation flight took off from Kabul airport. So ended 20 years of British endeavour in Afghanistan. Some was ineffectual but some inspirational. This is the story of a major success but with a decidedly bitter aftertaste.

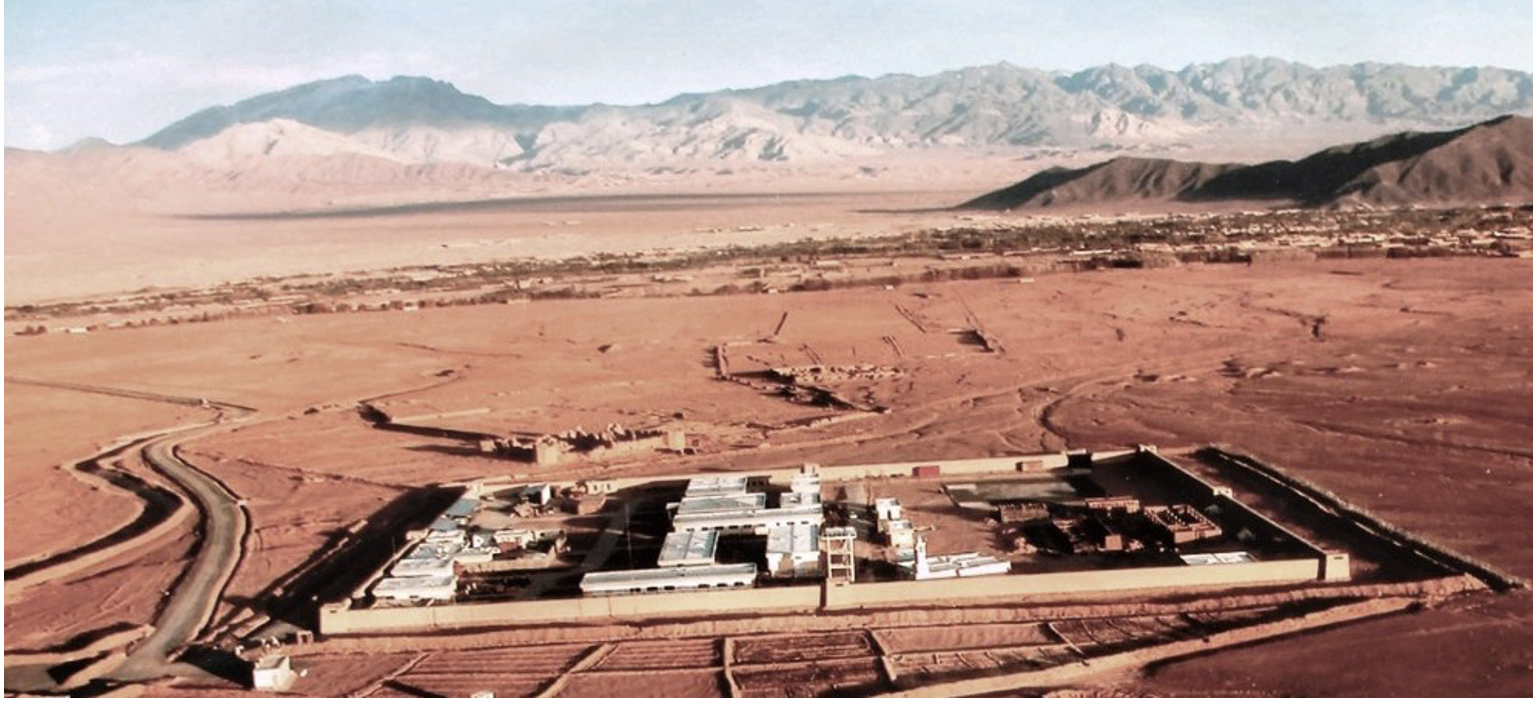

Just before midnight on Saturday August 14, 2021, a long line of beige coloured 4×4 vehicles snaked out of a high-walled fortress in Logar Province about 35 miles south of Kabul. The vehicles contained some 300 soldiers of Afghan Special Police Commando Force 333 (CF333). This was not the Afghan army evaporating and fleeing the Taliban advance. Quite the contrary. They were in uniform and fully armed. This was a British trained and funded unit ‘marching to the sound of the guns.’ Ignoring direct threats from the Taliban, they headed for Kabul to help with the defence of their capital city.

On the morning of the August 15, as the evacuation from Kabul airport got underway, the Commanding Officer (CO) and a squadron of around 40 soldiers were asked to deploy to the Baron Hotel at Kabul airport to provide protection for British passport holders. On the 17th, three of their number were evacuated with the remaining 37, told by British troops that their assistance was no longer required. Meanwhile, two other squadrons of CF333 were ordered to patrol the east of the city, while the remaining squadron defended the Police Special Units’ Headquarters. By evening, 333 was the last formed unit of Afghan soldiers still loyal to a regime whose President had fled in ignominy. Just before midnight, they were advised to save themselves. Some went to the airport. A few managed to get on flights.

Their last CO believes that several dozen members of CF333 have made it to the UK and about double that number are still in Afghanistan. Most of the abandoned 333 survivors have been in hiding. Others have fled to Pakistan, Iran and beyond. One has recently arrived by small boat from France. Those who still remain in Afghanistan are in constant danger.

Several 333 soldiers have been murdered by the Taliban. A few of their deaths have been publicised like the case of Noor Agha, a CF333 sniper, murdered in front of his wife and children. A more recent example was Riaz Ahmedzai, shot dead in front of his house. Another sniper was murdered in September 2021. The toll of deaths will continue to mount as the years pass with fewer and fewer receiving any press interest.

I have just been sent a rejection decision sent to one of CF333’s senior officers by the UK government’s Afghan Relocations and Assistance Policy (ARAP). It is quite clear that the officials deciding this man’s fate and that of his family, have no conception of what CF333 was. How could this be? Its history dates to the frantic weeks after 9/11; twenty-two years ago.

CF333 was one of the biggest achievements of the British government in Afghanistan. Its origins stem from when the (then) Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) attended a United Nations conference at Geneva in late 2001 and offered to lead the international community’s counter narcotics effort in Afghanistan.

It’s not just for the President anymore. Are you getting your twice-daily daily national security briefing? Subscriber+Members have exclusive access to the Open Source Collection Daily Brief, keeping you up to date on global events impacting national security. It pays to be a Subscriber+Member.

On returning to London there was a moment of trepidation as the sheer scale of the undertaking was contemplated. One of the more ambitious ideas was the creation of an Afghan Special Narcotics Force (ASNF), now known as CF333. The core concept was that it should comprise only Afghans. It should be Afghan-led and should report to the Afghan Interior Ministry. Only the funding and training should come from UK. Its existence and funding were briefed to the UK Parliament.

The force was created in double-quick time. It comprised 150 men led by an inspirational Brigadier who had fought under the Soviets against the mujahideen. Initially it had about 30 Toyota off-road vehicles soon supplemented by three Mi17 helicopters built in Ukraine. Two years later, at FCO’s request, it was doubled in size to 300 (including women) plus six choppers. Soon it developed the reputation of being the best Special Forces unit in all of Afghanistan. This video of U.S. General Nicholson visiting CF333 at its Logar base makes for painful viewing in light of what was to come.

The Brigadier’s whole ethos, learnt painfully during the failed Soviet presence in Afghanistan, was that 333’s role was to help the people by freeing them from the vicious and corrupt servitude of the opium producers and traffickers. He held educational sessions on the dangers of drugs and created a nationwide network of well-wishers. Whenever 333 arrived in a village they were welcomed, even feted. This was because they were evidently Afghans and not foreign soldiers. The sight of a disciplined Afghan force was the source of considerable pride amongst a population which associated men with guns with violent and rapacious behaviour. Later, 333 developed sophisticated Counter Terrorist and Counter Insurgency capabilities.

Cipher Brief Subscriber+Members enjoy unlimited access to Cipher Brief content, including analysis with experts, private virtual briefings with experts, the M-F Open Source Report and the weekly Dead Drop – an insider look at the latest gossip in the national security space. It pays to be a Subscriber+Member. Upgrade your access today.

The ARAP officials doubtless saw that the recent applicant had not worked for the British government but for the Afghan Interior Ministry. So, his application seemingly went straight into the ‘Rejected’ pile. Had they had any knowledge of the force’s origins, they would have seen that its Afghan identity was the whole purpose behind what was still an entirely British government creation. This may be why hundreds of CF333 soldiers and their families are still in mortal danger and the death toll continues to grow.

This is all a far cry from the days when every senior British government minister and general would visit 333’s fort as part of their Afghan visit programme, always ending with a speech about UK’s long-term commitment to Afghanistan. Now, that once proud unit is dispersed. The lucky ones are pizza-delivery riders in Liverpool or Exeter. Others live in fear in Afghanistan having destroyed or buried their unit badges, commendations and medals from the proudest days of their lives.

My close association with 333 ended in 2008. However, in January 2021, (seven months before the evacuation) I realised that the likely outcome of the Doha Accords (the Trump administration’s agreement with the Taliban) would place the men of CF333 at particular risk. I wrote to senior officials at the newly merged Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and copied the Ambassador in Kabul suggesting it was not too early to make preparations for the safety of 333 to whom we owed a duty of care. My email concluded “We can all see the trajectory of Afghan events and I would argue in favour of relocating people to UK now or soon, rather than wait until an emergency. We don’t want to be flying aircraft into Kabul at a time when Taliban could be on the streets of the city.”

My suggestion went unheeded, but it is not too late for the FCDO to intervene in the ARAP process and make sure that applicants from CF333 are fast-tracked to safety in the UK.

A crowdsource fund has been set up to support the members of CF333.

This column by Cipher Brief Expert Tim Willasey-Wilsey was first published by our friends at RUSI

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief because National Security is Everyone’s Business.

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source