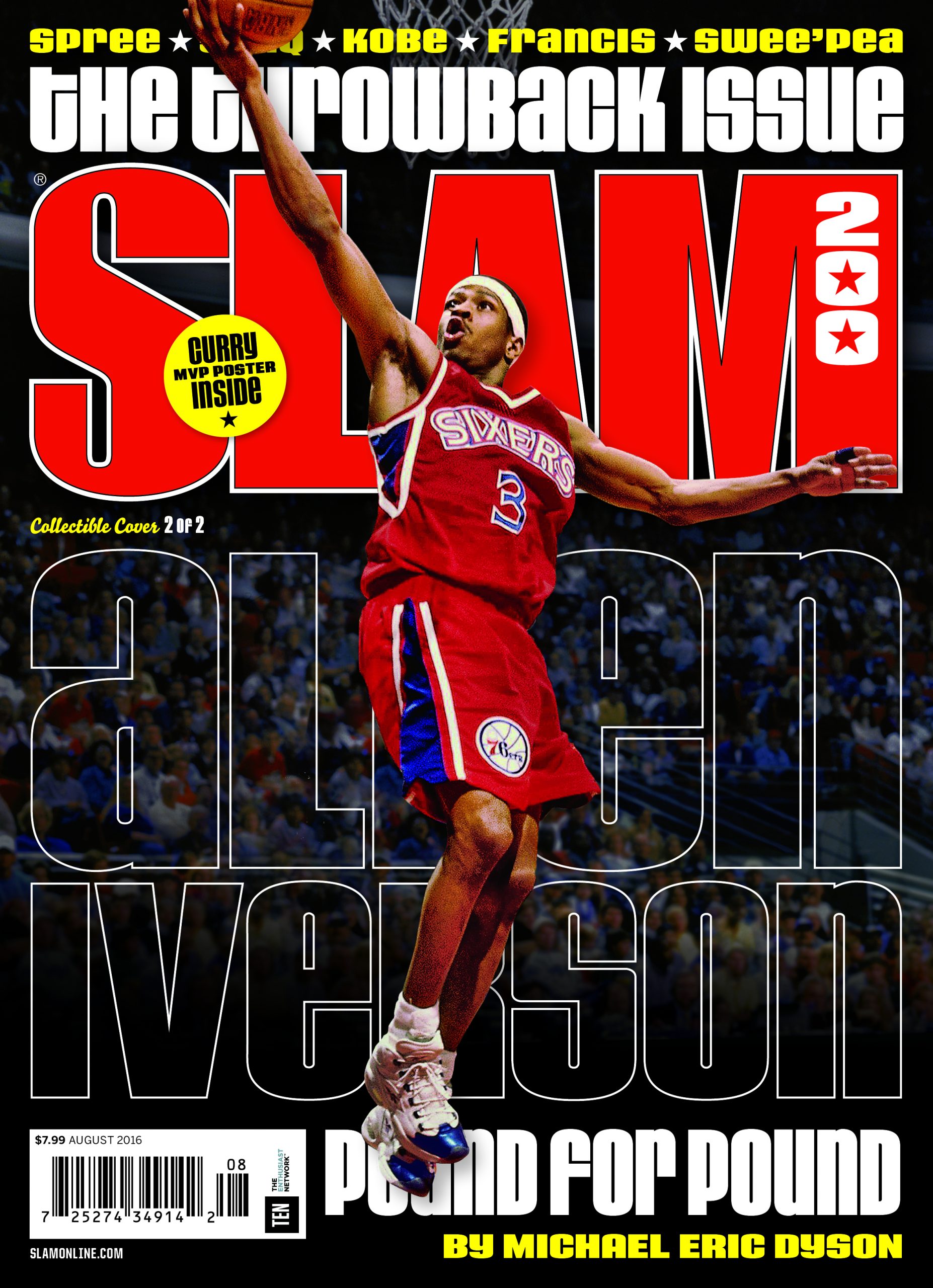

THE 30 PLAYERS WHO DEFINED SLAM’S 30 YEARS: Allen Iverson

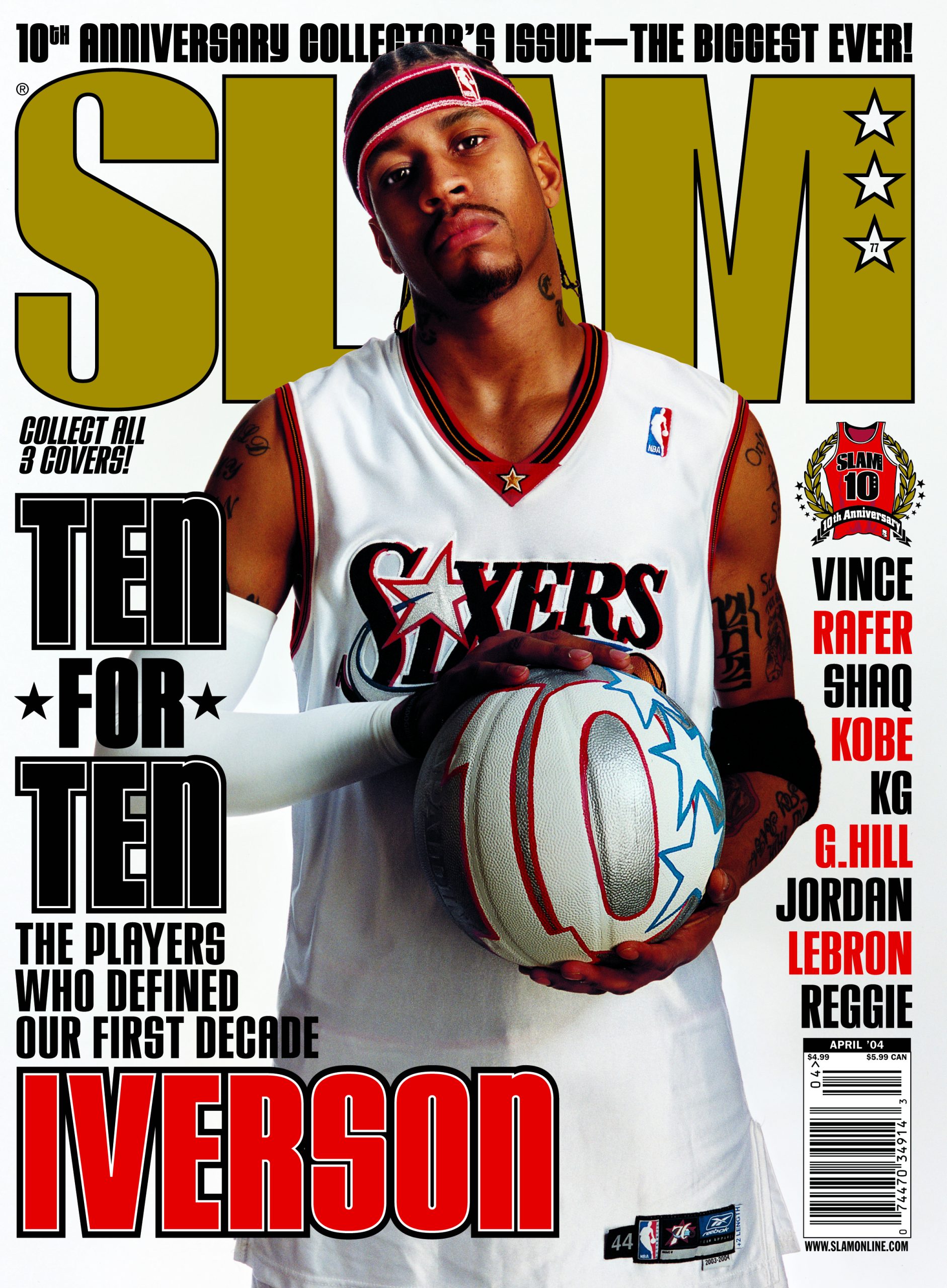

For three decades we’ve covered many amazing basketball characters, but some stand above the rest—not only because of their on-court skills (though those are always relevant), but because of how they influenced and continue to influence basketball culture, and thus influenced SLAM. Meanwhile, SLAM has also changed those players’ lives in various ways, as we’ve documented their careers with classic covers, legendary photos, amazing stories, compelling videos and more.

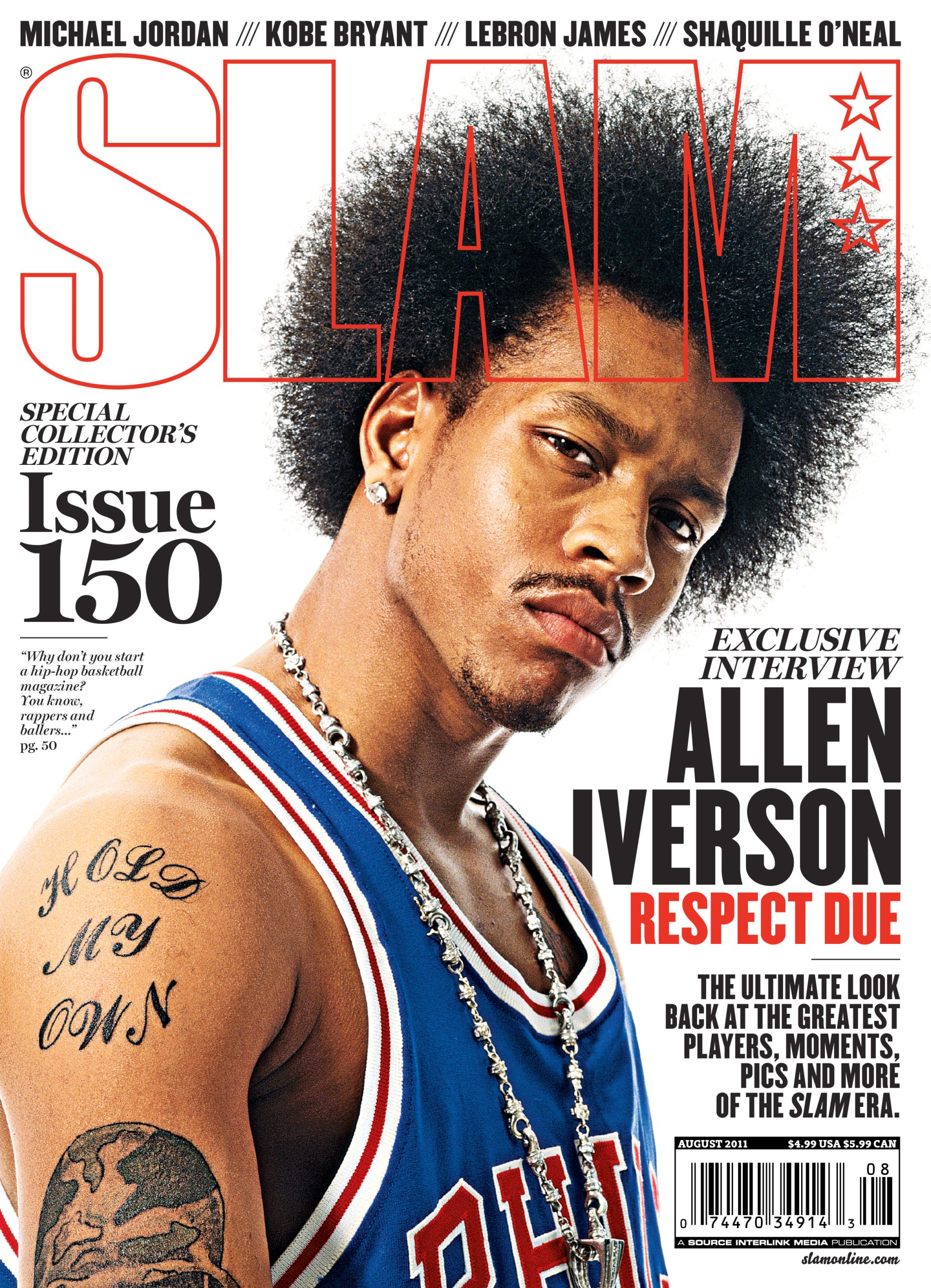

We compiled a group of individuals (programming note: 30 entries, not 30 people total) who mean something special to SLAM and to our audience. Read the full list here and order your copy of SLAM 248, where this list was originally published, here.

Forget how Merriam-Webster defines “iconic,” here’s how it should be defined: someone who or something that makes an enormous impact not only through his or her or its presence but also through his or her or its absence.

“Iverson left.”

Those were the first two words I remember hearing from Tony Gervino when he called from the NBA’s rookie orientation in Florida where we were shooting what would become the 1996 Draft fold-out cover. This was a huge shoot for us, and now we weren’t gonna have the first overall pick. (This news overshadowed the far funnier story of us having to keep a curious Todd Fuller—11th overall pick, Golden State Warriors—from wandering into the shoot. As an aside to an aside, if we included Golden State’s Draft pick, we probably would have taken out Kobe and wow how things could have been different.)

“Iverson left.” This wasn’t good.

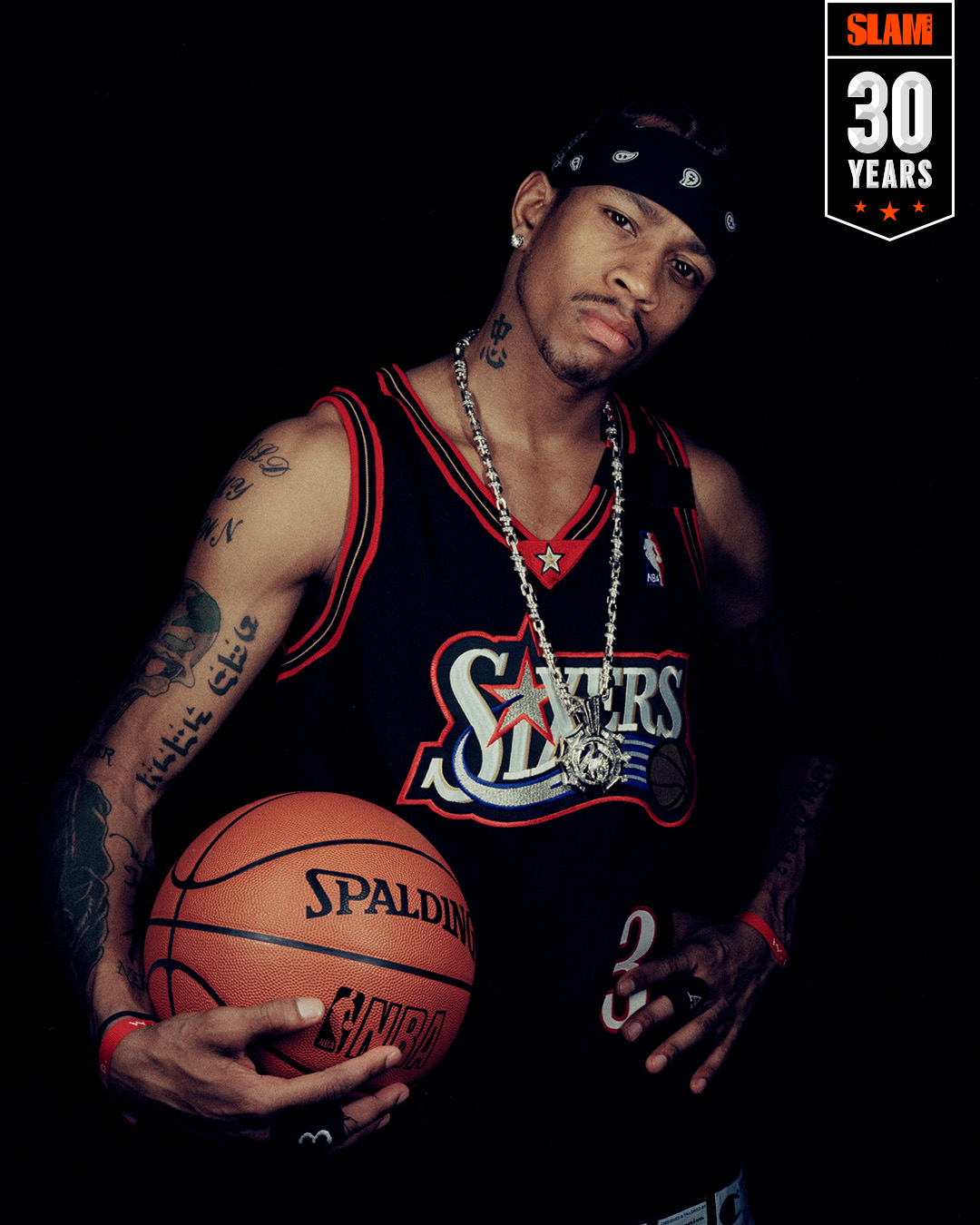

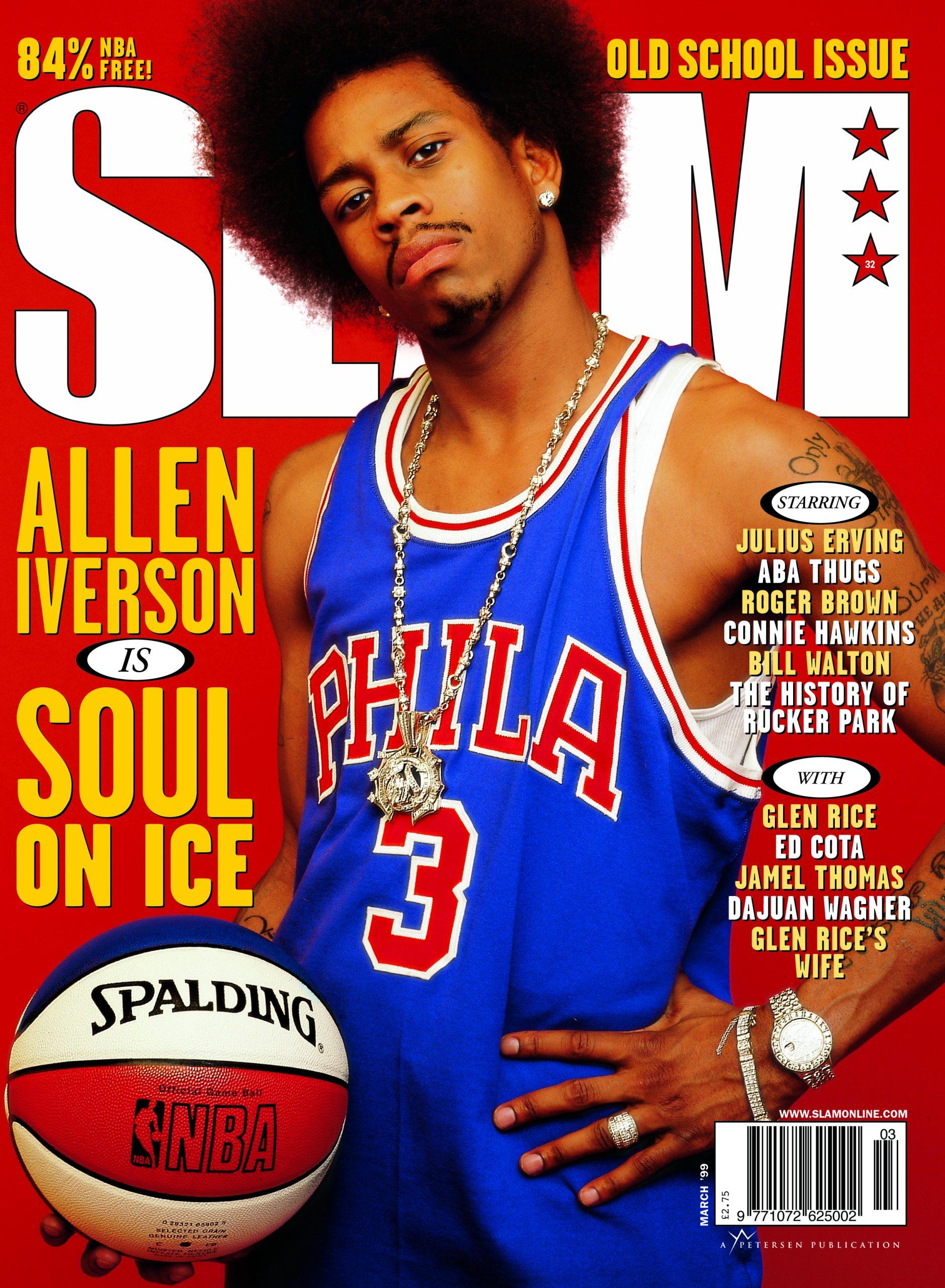

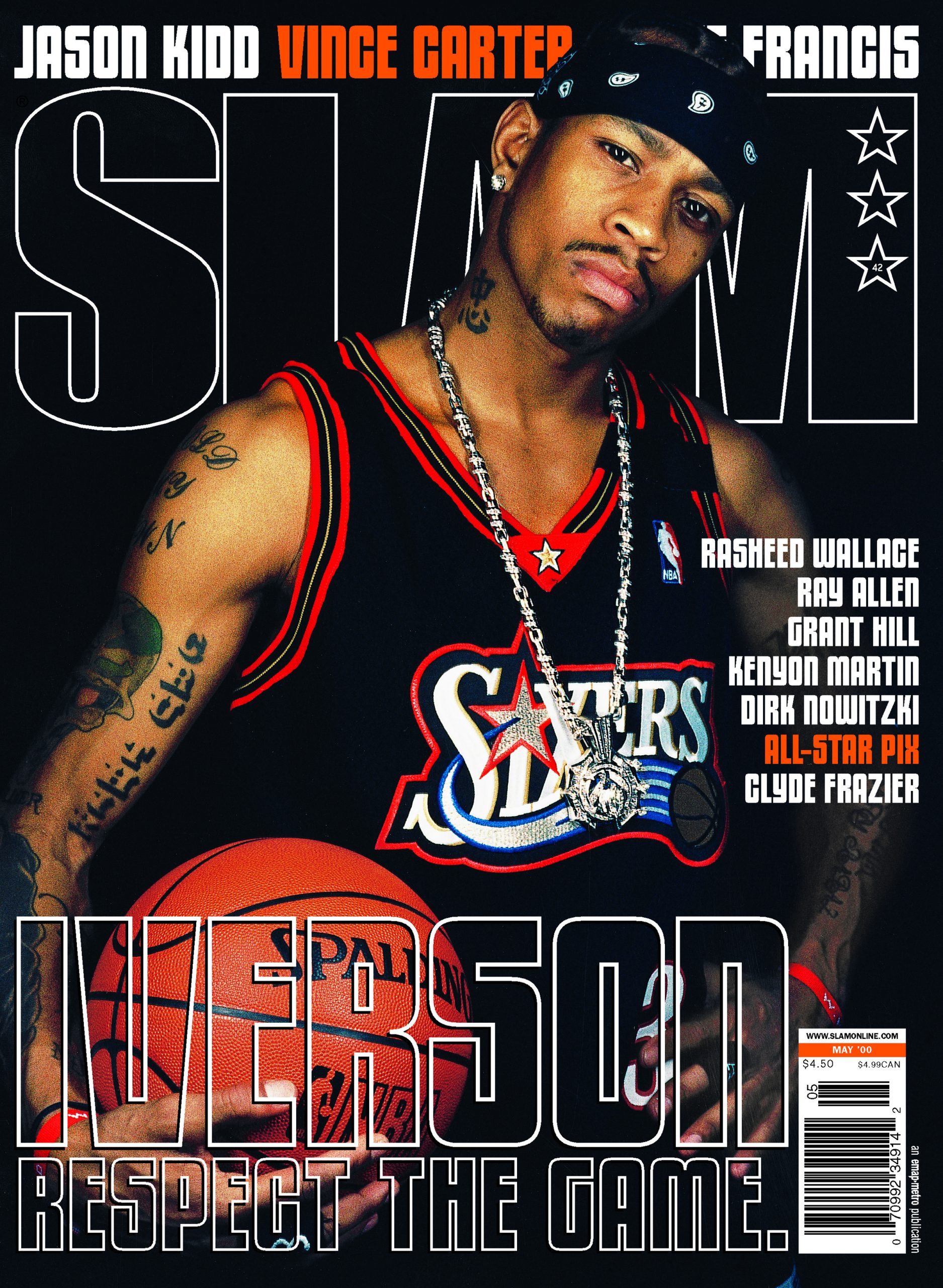

Over the years, we became incredibly familiar with those words, with that happenstance. Iverson was always there on the court and almost never there for photo shoots. He was 12 hours late for the SLAM 32 “Soul on Ice” shoot, dipped from practice (yes, yes, I know) entirely before we were supposed to shoot him for SLAM 42 the following year. We’d driven from New York to Philly, Clay Patrick McBride had everything set up, done the test shots and for a while we just stood around, hoping beyond hope he’d come back. He didn’t. We finally broke it all down and drove back. Instead, we eventually shot him in a room off to the side at an arena—grabbed him for literally a minute before a game and shot maybe one roll. For the record, every frame was amazing.

But it’s that rookie cover I keep going back to, and how Iverson’s absence ended up defining it better than his presence ever could have. It helped of course that Kobe Bryant and Ray Allen and Steve Nash ended up Hall of Famers (and Stephon Marbury and Jermaine O’Neal should be). In a way, Iverson being on there would have completed it. But in another way, his not being on there makes it cooler. This might just be me after-the-fact rationalizing, but I don’t think so.

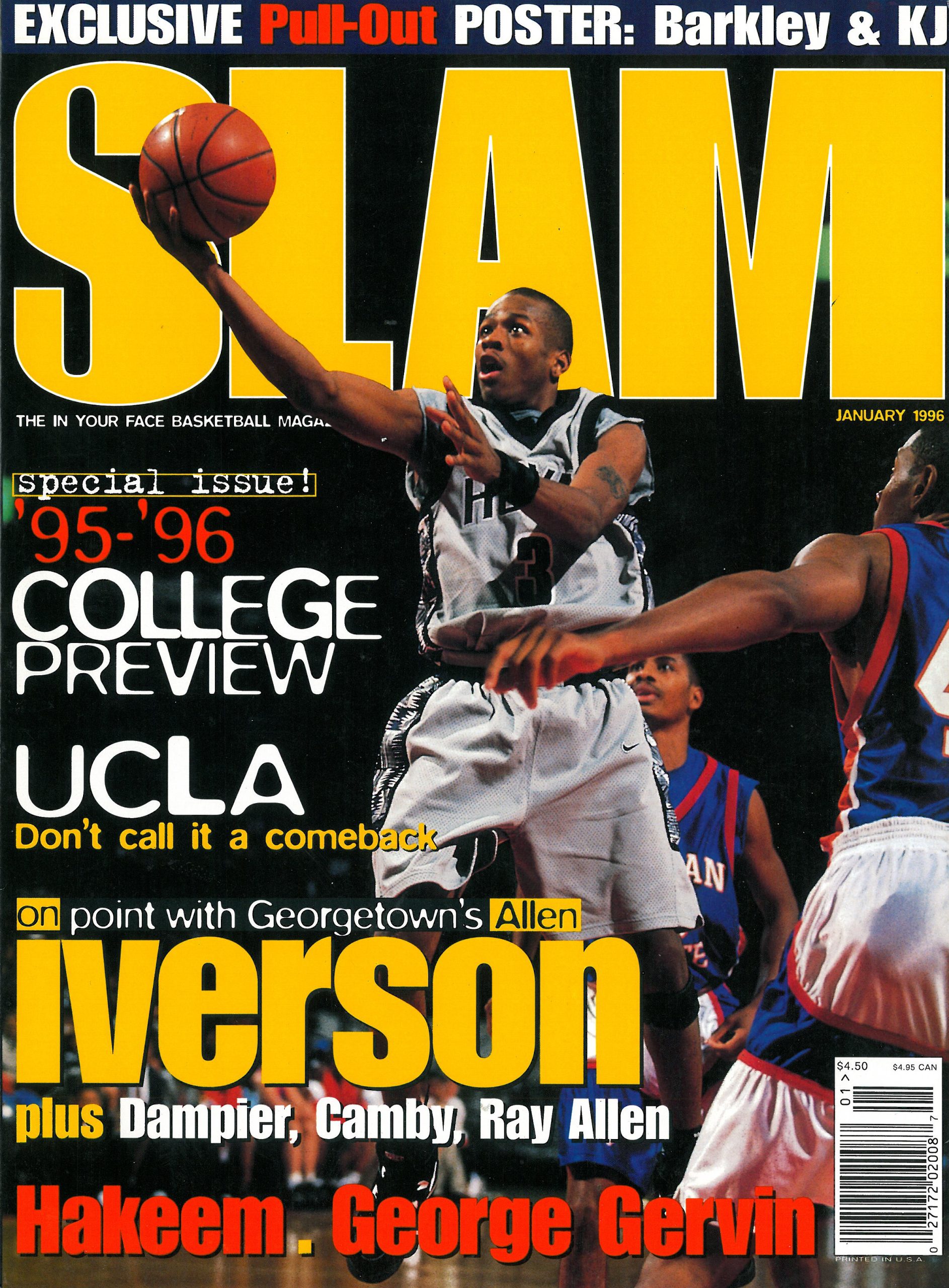

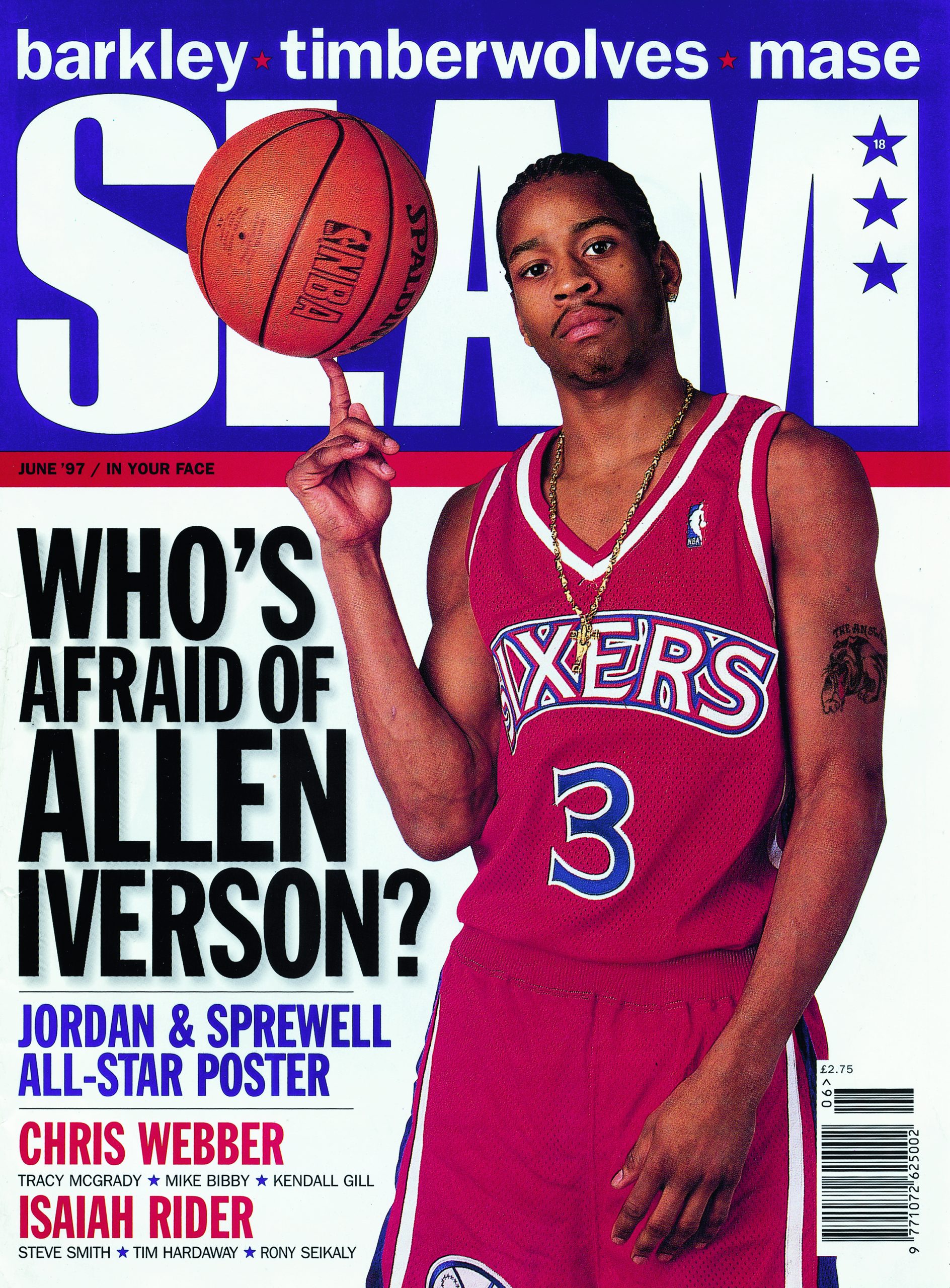

Iverson had already had his debut SLAM cover by then, an action shot while he was at Georgetown that Scoop had to convince Dennis would work. He’d get another in short order, “Who’s Afraid of Allen Iverson?” on the June ’97 issue. This was the proto-Iverson, a skinny little dude with one tattoo on his bicep, cornrows, a single long gold chain. This is who the mainstream sports media was railing against? By then he’d been Rookie of the Year, dropped 40-plus in five straight games, dropped Michael Jordan with a quick bap-bap, BAP-BAP crossover (and earned the GOAT’s ire in their previous matchup by proclaiming he didn’t have to respect anybody). Iverson loved Jordan, still does, but on the court? No love there.

Off the court though? I gave Iverson a copy of that “Who’s Afraid of Allen Iverson?” issue—we all used to carry copies of the latest issues to give to players—and in return he gave me a big hug. This was the first time I’d met him. But that’s how Allen Iverson was, and how he is. If he loves you, he shows it. I think of Sosa talking to Tony Montana in Scarface and saying, “There’s no lying in you, Tony.” There’s no lying in Iverson either. The last time I saw him, a couple years ago, he gave me a hug, too. “Who’s Afraid of Allen Iverson?” Someone who never interacted with him, that’s for sure.

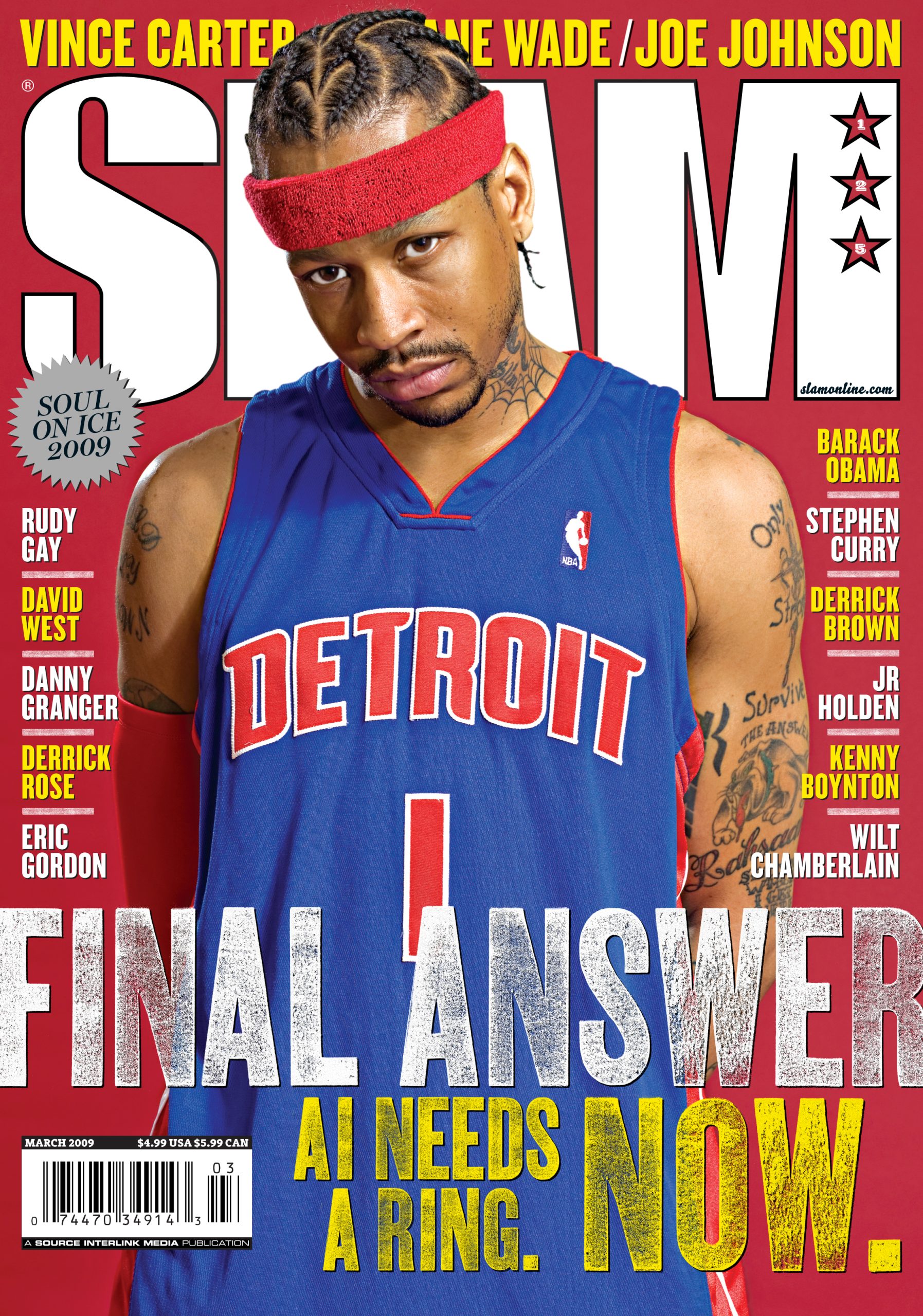

The “Soul on Ice” cover, which came nearly two years later (March ’99) happened with the NBA still in the throes of a lockout (note the “84% NBA Free!” in the upper left corner). It—both the cover shoot and the story—were part of a larger Iverson media push, so both the shoot and the interview for it were slotted in right before The Source Sports (The Source’s sports offshoot). We had to hire his hairstylist to both unbraid and re-braid his hair so he wouldn’t go into the Source Sports shoot still sporting a blowout. Of course in those pre-social media days, it was actually possible to keep a secret, so when the cover hit, no one was expecting it (an editor at Sports Illustrated actually asked Tony how we got him to wear a wig).

The interview happened in the morning and was something he wasn’t late for—I rode around NYC in a limo as he went to Modell’s HQ with Reebok (and stopped in the diamond district to get a massive piece of platinum and diamond jewelry repaired) and then out to Teterboro Airport. There, a Source Sports guy would accompany him on the flight and I’d catch a car service back to Manhattan. Now, Iverson is clearly not and never has been a morning guy unless he’s coming at it from the other side and preferably from the Main Line TGI Fridays. But he was still cool and compelling and heartfelt and honest to a fault—asked if he could be any other NBA player, he eschewed his childhood hero MJ (by then retired again) and went with Latrell Sprewell, who had yet to be reinstated by the NBA after choking coach PJ Carlesimo. It’s kind of crazy to think that at the time, he was still just 23 years old and hadn’t even been an All-Star yet. That summer, when KICKS Magazine opened to include all brands (it launched as Nike-only), he was on the cover of that, too.

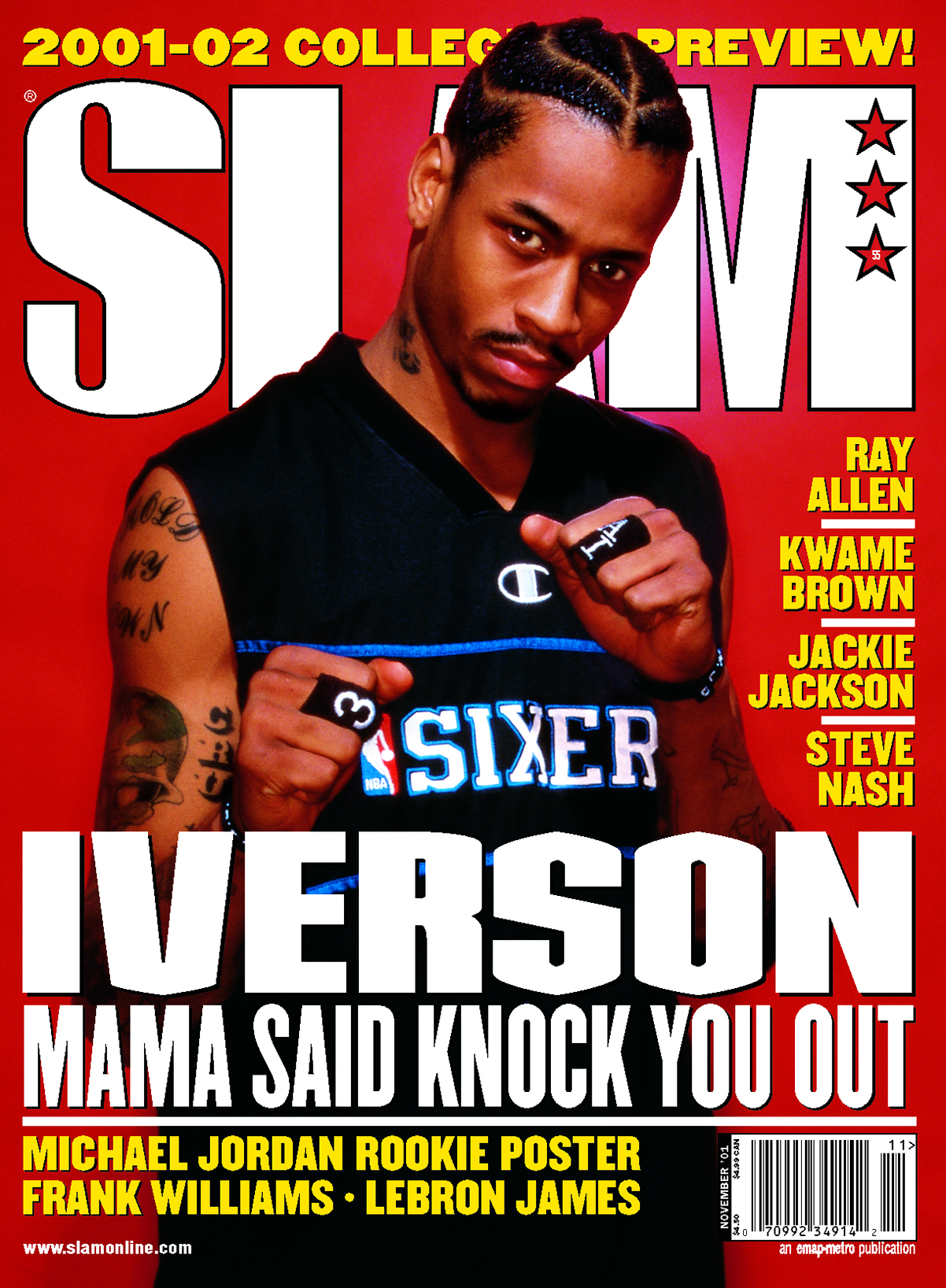

In 2001, Iverson became a god. There was the All-Star Game in DC in February, where he scored 15 of his 25 points in a furious fourth-quarter comeback from down 21 to win by 1. He was, of course, named MVP. On top of that he dropped 50-plus twice in the regular season and won MVP, dropped 50-plus twice more in a seven-game series against Toronto (and posted a season-high 16 assists in the closeout game), and took the undermanned Sixers to the Finals to face an undefeated Lakers juggernaut that he promptly defeated in Game 1 in Los Angeles with a 48-point masterpiece. To paraphrase then-SportsCenter anchor Dan Patrick, you couldn’t stop Allen Iverson or hope to contain him.

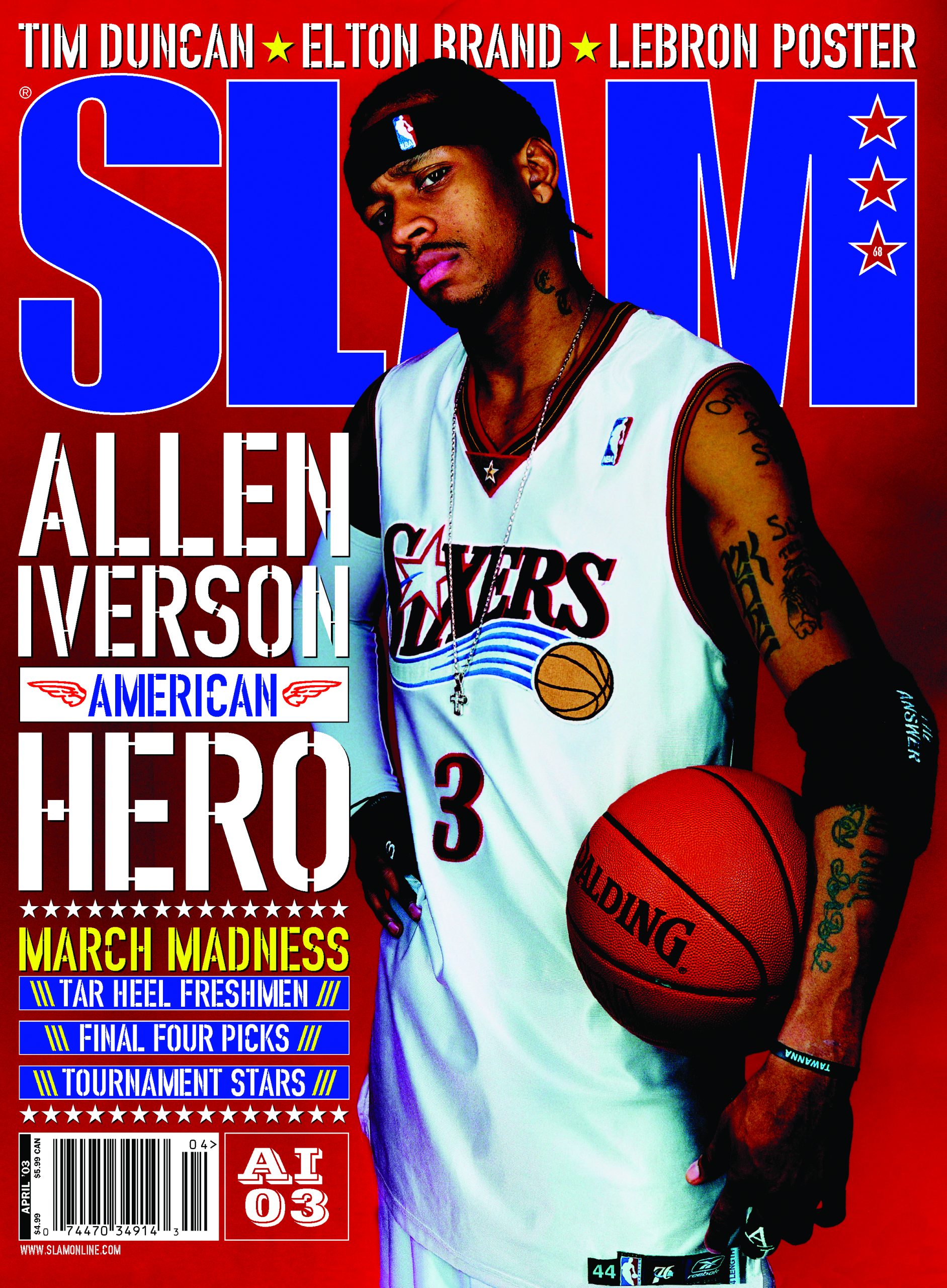

People tried, of course. That magical year in Philly did not lead to sustained postseason success, the clashes with Larry Brown did not cease, the local sports radio call-in types did not become rational. Iverson continued to be judged for what he didn’t do (show up to every practice, shoot at a high percentage) rather than what he did (carry a team on his back every f*cking game). I am half convinced that the analytic nerd obsession with “efficiency” was at least in part embraced because it discredited Iverson, a guy whose misses wouldn’t have even been shots for someone who didn’t have his crossover or first step or long arms or big hands or sheer fearlessness to drive again and again into the teeth of physical defenses.

Here was a guy who stood 6-0 (maybe), weighed 165 pounds (maybe) and led the League in minutes per game seven times! He averaged over 40 minutes a game for his career!

He was as superhuman as could be, but Iverson remained a hero to most for his humanity, in a way that even Jordan never was. Jordan always seemed to be above the fray even when he was in it, unreal even when he was standing right in front of you. The myth became the man. Iverson? He was the people’s champ long before Paul Wall, grindin’ out of VA before The Clipse. If you were a young NBA fan, Iverson was a guy who dressed like you, listened to the same music you did; he faced untold struggles and doubters and still he rose. He was a hip-hop icon who was himself of hip-hop, with the cornrows and the throwbacks and the jewelry and even the (unreleased) album. He did commercials with Jadakiss, pushed a Bentley, kept crazy hours and still dropped 45 whenever he felt like it.

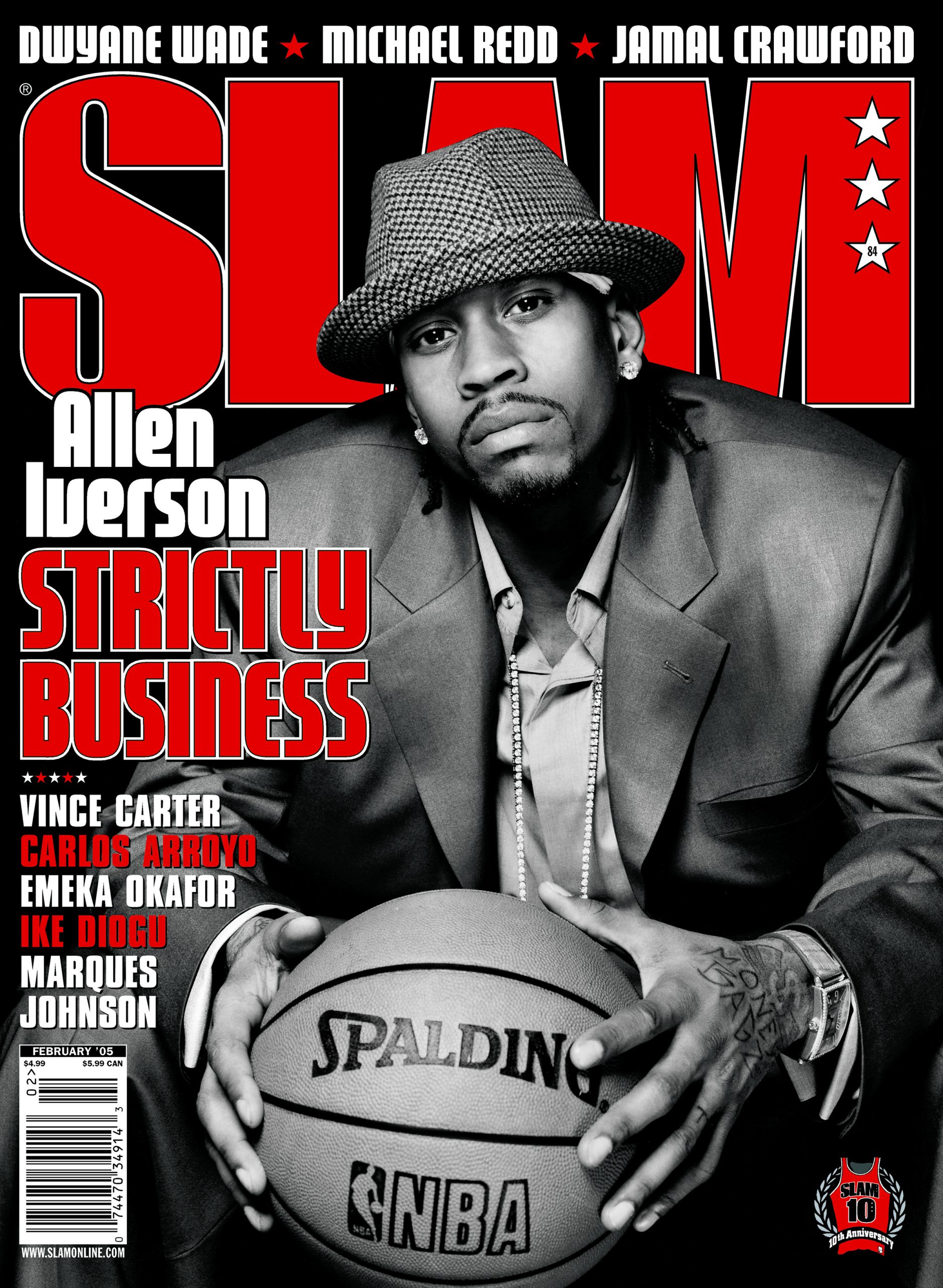

Let’s talk about the throwbacks for a minute. His wearing his own Wilt-era No. 3 Hardwood Classics jersey on the cover of SLAM 32 was instrumental in kicking off the whole craze and making the Mitchell & Ness flagship store in Philly a must-hit spot for everyone (including us). AI even rocked throwbacks on the bench when he was out—I distinctly remember him wearing an Abdul-Jabbar Bucks joint in Milwaukee—but, despite the NBA brand synchronicity, the NBA commissioner didn’t love it. There were rumblings of an NBA dress code long before one was ever implemented. So when we were brainstorming ideas for Iverson on the February ’05 cover, I came up with this: What if we shoot Iverson in a suit?

The first question was whether he’d be down to do it, which he was. Phew. The second question was, did he even own a suit? The last time he wore one was probably when he got drafted. The answer to that, at least in terms of whether he had one he’d be willing to be shot in, was no. So he had one made. If you look at that cover with its black-and-white Atiba Jefferson photo, you’ll notice the suit is kind of baggy. So is the fedora, somehow. He’s like a hip-hop Humphrey Bogart. I ran into Que Gaskins, Iverson’s long-time Reebok guy, some years later, and he told me that Iverson kept telling the tailor everything had to be bigger, no, bigger than that, so many times that the guy finally just threw up his hands and quit. Well, nearly quit anyway. In October of that year, David Stern finally instituted the long-anticipated NBA dress code and hey, at least Allen Iverson already had a suit.

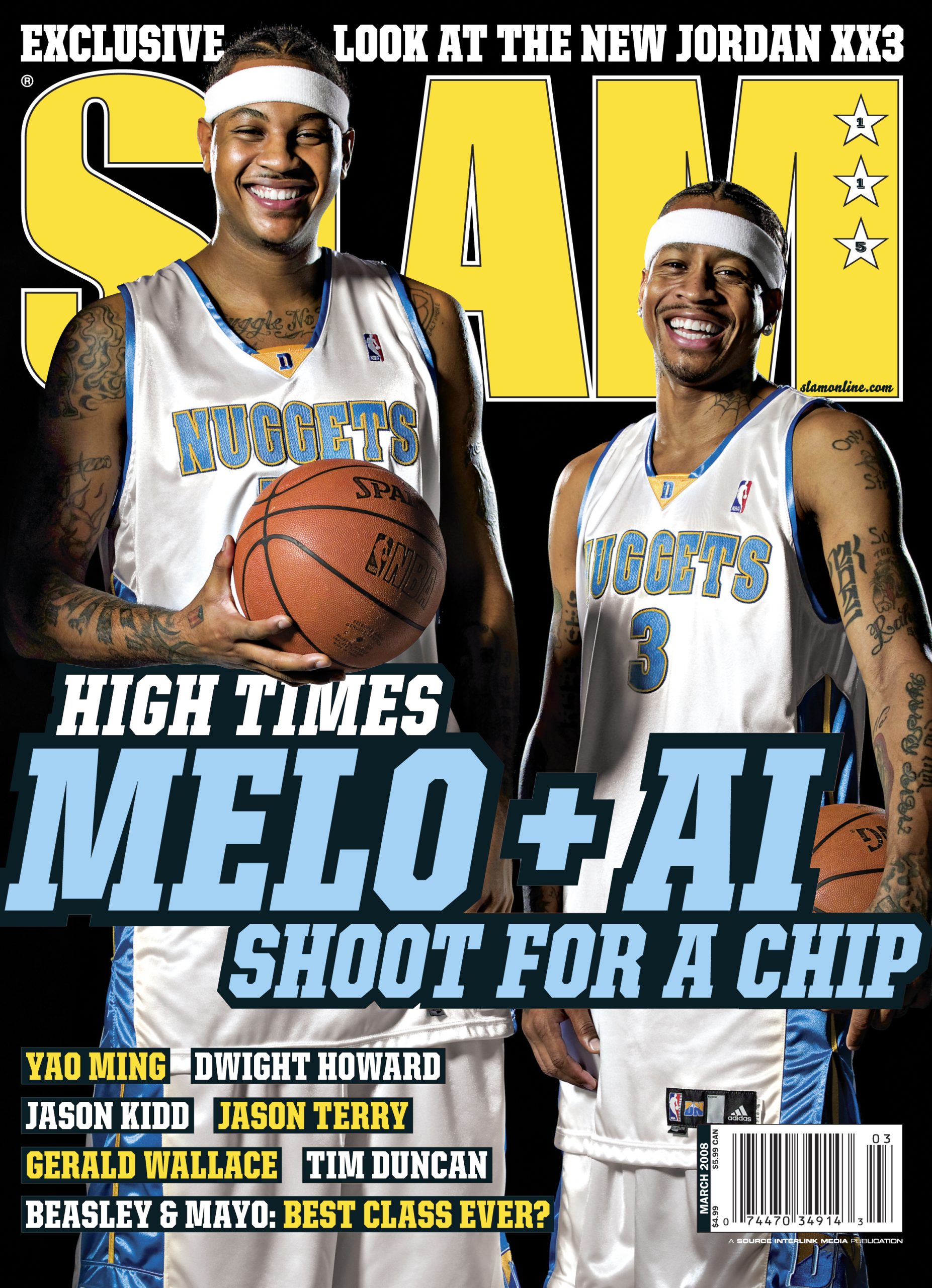

AI’s career didn’t end the way anyone wanted it to, but it lasted long enough for him to get endless bouquets from the generation that came after his—fitting for someone who never hesitated to pay homage himself, once wearing Dr. J’s No. 6 instead of his own No. 3 in an All-Star Game. Traded to Denver, he teamed with a young Carmelo Anthony, his own 6-7 doppelganger complete with ink and braids and a headband. Their SLAM cover together in March 2008 is a frozen moment of laughter, two guys clearly delighted in each other’s presence. And it wasn’t just Melo; that whole class of 2003 was filled with Iverson fans, from LeBron—forced to cover up his own tattoos in high school—to Dwyane Wade, who wore No. 3 because of him.

Allen Iverson inspired us, too. Here was a guy who, from the very start, was uncompromising in what he believed, in what he did, in what he said. With apologies to the great Kool G Rap, he was the realest. It shone through in everything, from his on-court performances to photo shoots to Reebok commercials. There were layers to go through to get to him of course, but by the time you did get to him, you knew exactly where he stood.

Yeah, he could be exasperating, especially to photographers (and writers) with schedules and families and whatnot, but even they got past it when they realized AI wasn’t being malicious or big-timing them or anything, it’s just who he was. But his presence—or his absence—was always huge. We always did what we had to do to get him, no matter how many times we had to reschedule. After all, we knew what missing him was like, and we didn’t want that to happen again.

Photo via Getty Images. Portrait by Clay Patrick McBride.

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source