India’s stock market is shut for the day. Central government offices are only open for half the day. Neighbourhood watch parties have been organised across the country. And tens of millions of Indians are tuned into one event: the consecration of a temple to the Hindu god Ram in the city of Ayodhya.

On Monday, just past noon local time, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi will join priests to inaugurate the temple, whose launch in many ways also serves as the start of his campaign to be re-elected for a third term in office in national elections due to be held between March and May.

The trust in charge of the temple, whose construction is still under way, has invited an estimated 7,000 people — politicians, leading industrialists, sports stars and other public figures.

But while Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government has pitched the event as a national celebration, the temple’s history is grounded in what many have dubbed one of modern India’s darkest chapters — one that has shaped the country’s politics and that cracked open deep religious fault lines in its society.

Here’s a look at the tortured history of the spot where the temple is being built — and the controversies surrounding it.

What is the controversy behind the Ram temple?

The temple is being built on a contentious piece of land in the northern Indian city of Ayodhya, at a spot that many Hindus believe was the birthplace of Ram, a much-worshipped god who in the religion epitomises the victory of good over evil.

But until the morning of December 6, 1992, it was the Babri Masjid, a mosque built in 1528 and named after the Mughal king Babur, that stood at that place. A mob of Hindu nationalists pulled down the mosque, chanting religious slogans, after more than a decade of an angry, and at times violent, campaign.

After years of being closed to the public, in November 2019, India’s Supreme Court ruled that the site must be handed over to a trust that would be specially set up to oversee the construction of a Hindu temple.

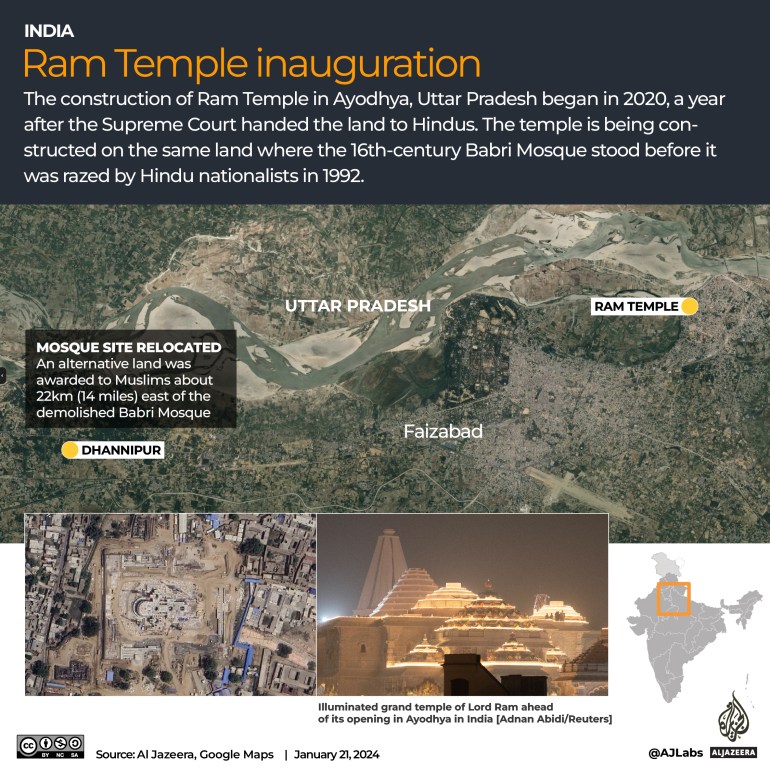

A separate piece of land in Dhannipur village on the outskirts of Ayodhya, was allocated to Muslims for a mosque that may serve as a replacement for the Babri Masjid. Its construction is yet to begin.

“Through the highest court now, we have established a principle of creating an unbreakable divide between Hindus and Muslims, that they cannot live side by side,” said writer and academic Apoorvanand on the “five-acre justice,” a term Indians have penned over the size of the reallocated land.

While some segments of India’s population cheered on the judgement, others criticised it for lacking a sound legal basis and compromising on India’s secular and democratic constitutional ethics.

Locals have also pointed to the history of harmonious co-existence between the two communities in Ayodhya, even at places of worship. The ruling also sparked fears that it was emboldening right-wing Hindus across the country to launch similar efforts to raze other mosques.

Although the Ram Temple controversy goes back decades, Apoorvanand says that Monday’s event is “also a final announcement of, in a way, Hindus handing over their religion to the will of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh.” The RSS is the Hindu-nationalist mothership of the BJP and its far-right partner organisations.

The temple’s inauguration seals the site as a place of Hindu worship, and comes after years of legal tussles and even violent riots over the land and its legacy.

Major events in the divide over the Ram temple

The first recorded instance of conflict over the site was in 1853, when a Hindu sect asserted that a temple had been demolished during Babur’s era to make way for the mosque.

Tensions especially started to take a turn in 1859 when British colonial rulers partitioned the building into separate sections – the inside for Muslims, and the outer court for Hindus.

In 1949, just two years after the subcontinent won independence, the mosque turned into disputed property. Police reports show that Hindu idols were brought into the mosque and its gates were closed. No Muslim prayers were offered at the mosque after that. In 1950, several civil suits were filed with both communities laying claim to the site.

But it was outside the courts that the fate of the Babri Masjid was ultimately decided.

In the 1980s, the BJP that now dominates Indian politics was largely a fringe party. But it built political momentum around a nationwide campaign to build a temple in the place of the mosque, led by then party chief Lal Krishna Advani, who would later serve as India’s deputy prime minister (1998-2004).

Under pressure from the BJP and its Hindu majoritarian allies and the support they were galvanising, the government of then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, of the Indian National Congress, allowed a court decision to open the locks of the Babri Masjid site to go unchallenged in 1986.

That, however, only emboldened the BJP-led agitation. In 1990, Advani led a long rally over more than a month through the heart of India, building support for the Ram temple. Modi, then a young and rising party worker in the western state of Gujarat, helped organise the rally.

Then, on December 6, 1992, Hindu mobs tore down the Babri Masjid. Ensuing riots across the country killed about 2,000 people.

Following years of back and forth in court, the Supreme Court issued its landmark ruling in 2019.

The court acknowledged that both the surreptitious manner in which idols were brought into the mosque in 1949 and the demolition in 1949 were crimes. Still, by essentially ordering no consequences for those offences, the court created a scenario where Indian Muslims are “disappointed to see no remorse”, and feel there is little recourse for their concerns, says Apoorvanand.

Where exactly is the contested site?

The Ram temple is being built near the banks of the Sarayu River, which runs past Ayodhya and is mentioned in ancient Hindu scriptures. Ayodhya is in India’s northern and most populous state, Uttar Pradesh.

Officially known as Shree Ram Janmabhoomi Mandir, it has been constructed in the Nagara style of architecture, which is common in northern India and features tall steeples and a stone platform with steps leading up to the temple.

When will the Ram temple consecration take place?

The consecration is scheduled for just after 12pm local time (06:30 GMT) on Monday, January 22.

Many of the wings of the temple are still under construction, and some of Hinduism’s foremost seers, the four Shankaracharyas, have objected to the opening, saying that consecrating an incomplete temple goes against Hindu scriptures.

Nonetheless, the government, and the trust in charge of the temple, have insisted that the consecration does not violate any tenets of the faith.

Monday’s event will include a grand procession of idols to be taken into the building, and a four-foot statue of a child Ram being placed in the inner sanctum. Priests will join Modi for the actual ceremony, expected to last for half an hour.

Modi’s government has also planned live screenings of the event across the country. Some Indian embassies have also invited members of the Indian diaspora to screenings.

As Hindus across Ayodhya decorate streets and join celebratory rallies, messages are circulating among Muslims to remain at home as a precaution for their safety.

The constructed portion of the temple will be open to devotees and the public starting January 23. And as the temple’s doors open to them, so does a path to an economic boost for Ayodhya.

About 100 private jets are expected to touch down in Ayodhya ahead of the inauguration and retailers say they have run out of gold and gold-plated statues of Ram.

Property prices in Ayodhya have also skyrocketed as the city is set to become a pilgrimage and tourism hotspot.

How are Modi and India’s 2024 elections linked to the Ram temple?

Building the Ram temple at the spot where the Babri Masjid once stood has been one of the BJP’s three foundational promises — the end of Jammu and Kashmir’s semi-autonomous status, which was scrapped in 2019, and a uniform civil code for personal laws are the others.

Modi’s consecration of the temple fulfils that decades-long pledge, and comes just weeks before national elections.

The Ram temple movement has already paid rich dividends to the BJP’s political fortunes. The party won just two seats out of 543 in the lower house of parliament in 1984. A little more than a decade later, in the first national elections after the Babri Masjid’s demolition, it surged to become India’s single-largest party, winning 161 seats.

Its first stint in office lasted just 13 days — because of its association with the mosque demolition, most other parties were unwilling to form alliances that the BJP needed to get to the majority mark of 272 seats in parliament.

But as its brand of Hindu nationalism slowly gained acceptability, it came to power again in 1998, and ruled with allies until 2004. After a decade out of power, it stormed back into office under Modi, the most unapologetically Hindu nationalist leader the party has had.

On Monday, Modi will look to cement that legacy still further.

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source