The United States has halted the shipment of some types of heavy bombs to Israel and US President Joe Biden has also pledged to halt the supply of some offensive weapons and artillery shells to the country if it goes ahead with its assault on Gaza’s southernmost city of Rafah.

Here’s what we know so far.

What is the US saying?

Biden issued this warning, possibly his starkest yet against Israel, during an interview with CNN on Wednesday. In the same interview, he also said that the US would continue to supply defensive arms such as Iron Dome interceptors, underlining his continued support for Israel’s defence.

US officials said on Wednesday that the US had paused a shipment of heavy bombs, including 1,800 of 2,000-pound (907kg) bombs and 1,700 of 500-pound (227kg) bombs.

The Washington-based news outlet Politico reported that the weapons held back also include Boeing’s Joint Direct Attack Munitions, which are guidance kits that convert “dumb” bombs dropped in free-fall, ballistic trajectory into precision-guided ones.

These weapons had been included in an earlier shipment for Israel, approved before the recent supplemental aid package authorised by the US Congress in April, which assigned $26.38bn for Israel, including $9.1bn for humanitarian purposes.

At a US Senate hearing on Wednesday, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin said the US is reviewing near-term security assistance to Israel in the context of Israel’s ongoing attacks on Rafah.

“We’ve been very clear…from the very beginning that Israel shouldn’t launch a major attack into Rafah without accounting for and protecting the civilians that are in that battle space,” Austin said.

What damage can heavy bombs cause?

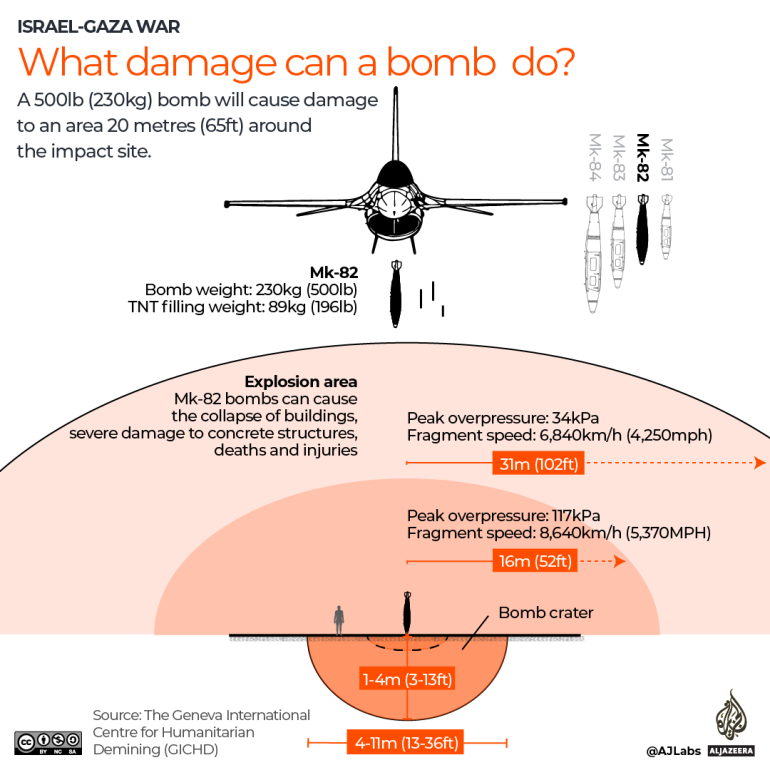

On explosion, a 500-pound bomb can severely harm or kill everything or anyone within a 20-metre (65 feet) radius. A 2,000-pound bomb has a destruction radius of 35 metres (115 feet), according to the Project on Defense Alternatives (PDA), which conducts defence policy research and analysis.

Depending on the type of surfaces it hits, a 500-pound bomb can create a crater of, on average, 25 feet (7.6 metres) across and 8.5 feet (2.6 metres) deep. A 2000-pound bomb will carve out a crater 50 feet (15 metres) across and 16 feet (5 metres), according to the PDA.

A 2015 report by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) says of the 2000-pound bomb: “The pressure from the explosion can rupture lungs, burst sinus cavities and tear off limbs hundreds of metres from the blast site.”

Israeli forces used 2,000-pound bombs on the Jabalia refugee camp on October 31, according to analysis by The Guardian and The New York Times. Two impact craters estimated to be 40 feet (12 metres) wide were identified.

Is it legal for Israel to use these bombs in Gaza?

Aerial bombing in densely populated areas is not explicitly illegal in international humanitarian law. However, civilians cannot be targets of the bombing and any civilian casualties must be “proportionate” with a specific military aim. Both the Additional Protocol I of the 1949 Geneva Conventions and the Hague Convention of 1907 lay down these rules. Israel is a signatory to both.

If the numbers of civilian casualties are not proportionate and are “clearly excessive” as measured against any direct military advantage, then the attack qualifies as a war crime according to the statute of the International Criminal Court, which is investigating Israel’s war on Gaza.

How has Israel reacted to Biden’s statement on offensive weapons shipments?

Israel asserts that its only interest is in destroying Hamas and that it does not target Palestinian civilians. It claims to take all precautions to avoid unnecessary casualties. It has justified its assault on Rafah with the claim that the city is home to Hamas’s remaining battalions. More than one million civilians have taken shelter there from the Israeli bombardment on other parts of the Gaza Strip over the past seven months, however.

On Thursday, Gilad Erdan, Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations told Israeli public radio Kan: “This is a difficult and very disappointing statement to hear from a president to whom we have been grateful since the beginning of the war.”

Erdan said Biden’s warning would bolster the positions of Iran, Hamas and Hezbollah.

“If Israel is restricted from entering an area as important and central as Rafah where there are thousands of terrorists, hostages and leaders of Hamas, how exactly are we supposed to achieve our goals?” he said.

How much military aid does the US provide to Israel?

The US sends Israel about $3bn a year, most of which is provided as Foreign Military Financing (FMF).

The US has historically supplied substantial foreign aid to Israel; a total of $297bn (adjusted for inflation) between 1946 and 2023, $216bn of which was in military aid and $81bn in economic aid, according to data from the US Agency for International Aid (USAID). Israel is the largest cumulative recipient of US aid since its founding.

After the Hamas attack on October 7, the US sent navy ships such as guided missile cruisers armed with naval guns and destroyers alongside $2bn worth of munitions to Israel.

Israel is reliant on US military aid because of a global ammunition shortage following the wars in Gaza and Ukraine, Israeli daily business newspaper, the Calcalist reported, adding that while the Israeli military has avoided conceding this in public, Major General Eliezer Toledano admitted in March that the army is reducing air attacks in order “to better manage the economy of armaments”.

Has the US paused military aid to Israel before?

Yes. The US paused military aid to Israel in 1982, when then-President Ronald Reagan imposed a six-year ban on cluster weapons sales to Israel. This followed a congressional investigation which revealed that Israel had used the weapons on areas with civilian populations when it invaded Lebanon in 1982.

What is happening in Rafah?

Israel launched a military offensive on Rafah and seized control of the Gaza side of the Rafah border crossing with Egypt, cutting off access to humanitarian relief, on Tuesday, hours after Hamas agreed to a ceasefire deal. This followed an overnight assault on the area using warplanes which killed at least 12 civilians.

After Israel’s relentless bombardment of the Gaza Strip since the start of the war on October 7, more than one million internally displaced Palestinians have taken shelter in Rafah – many of them previously displaced from other parts of Gaza following Israel’s orders to evacuate from those areas. More than 34,000 Palestinians have been killed over the course of the war, most of them women and children. Thousands more are missing, feared dead under the rubble.

As Rafah is the southernmost city of the Gaza Strip, observers say that civilians now have nowhere else to go.

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source