Somali lawmakers elect president voted out 5 years ago

“Victory belongs to Somali people, and this is the beginning of the era of unity, the democracy of Somalia and the beginning of the fight against corruption,” Mohamud said after winning the vote.

He added that he saw “a daunting task ahead” after winning back authority.

The first round of voting was contested by 36 aspirants, four of whom proceeded to the second round. With no candidate winning at least two-thirds of the 328 ballots, voting then went into a third round where a simple majority was enough to pick the winner.

Members of the upper and lower legislative chambers picked the president in secret balloting inside a tent in an airport hangar within the Halane military camp, which is protected by African Union peacekeepers. Mohamud’s election ended a long-delayed electoral process that had raised political tensions — and heightened insecurity concerns — after President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed’s mandate expired in February 2021 without a successor in place.

Mohamed and Mohamud sat side-by-side Sunday, watching calmly as the ballots were counted. Celebratory gunfire rang out in parts of Mogadishu as it became clear that Mohamud had defeated the man who replaced him.

Mohamed conceded defeat, and Mohamud was immediately sworn in.

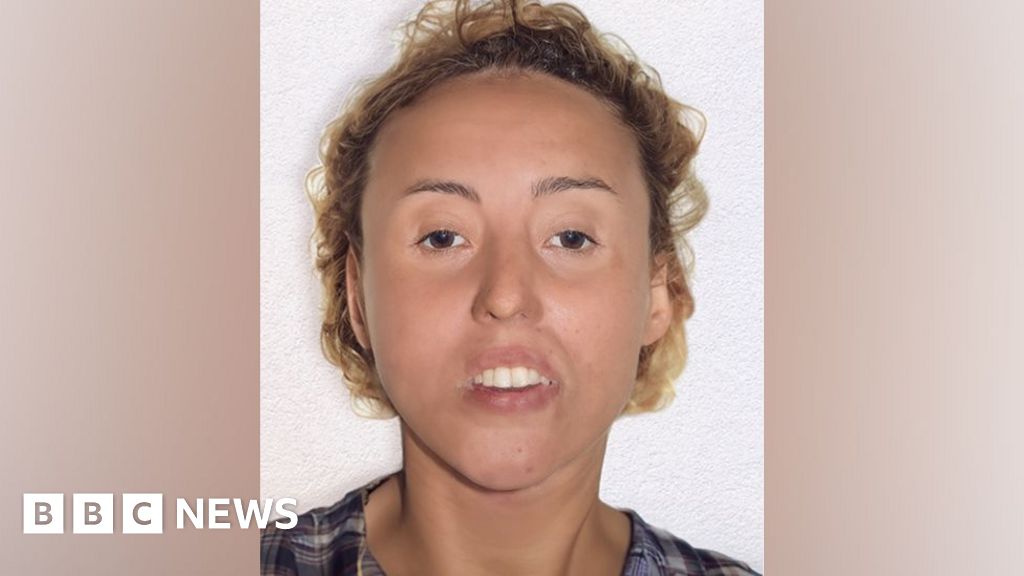

The 66-year-old Mohamud is the leader of the Union for Peace and Development party, which commands a majority of seats in both legislative chambers. He also is well-known for his work as a civic leader and education promoter, including for his role as one of the founders of Mogadishu’s SIMAD University.

The Somali government under Mohamed faced a May 17 deadline to hold the vote or risk losing funding from international partners.

Mohamed — who is also known as Farmaajo because of his appetite for Italian cheese — said on Twitter while voting was underway that it was “a great honor to lead” Somalia.

For Mohamed and his supporters, Sunday’s loss will be disappointing after he rose to power in 2017 as a symbol of a Somali diaspora eager to see the country prosper after years of turmoil. Mohamed leaves behind a country even more volatile than he found it, with a reported rift in the security services and the constant drumbeat of al-Shabab attacks.

Analysts had predicted that Mohamed would face an uphill battle to be reelected. No sitting president has ever been elected to two consecutive terms in this Horn of Africa nation, where rival clans fight intensely for political power. In winning the vote, however, Mohamud overcame the odds as no former president had ever launched a successful return to the office.

A member of the Hawiye clan, one of Somalia’s largest, Mohamud is regarded by some as a statesman with a conciliatory approach. Many Somalis hope Mohamud can unite the country together after years of divisive clan tensions but also take firm charge of a federal government with little control beyond Mogadishu. Mohamud promised during campaigns that his government would be inclusive, acknowledging the mistakes of his previous government that faced multiple corruption allegations and was seen as aloof to the concerns of rival groups.

The new president “will get an opportunity to heal a nation in desperate need of peace and stability,” said Mogadishu resident Khadra Dualeh. “The country doesn’t need celebrations; we did that for Farmaajo. Enough celebration. We need prayer, being sober and planning how to rebuild the country.”

Al-Shabab, which has ties with al-Qaida, has made territorial gains against the federal government in recent months, reversing the gains of African Union peacekeepers who once had pushed the militants into remote areas of the country.

But al-Shabab is threatening Mogadishu with repeated assaults on hotels and other public areas. Despite the lockdown, explosions were heard near the airport area as legislators gathered to elect the president.

To discourage extremist violence from disrupting the elections, Somali police put Mogadishu, the scene of regular attacks by the Islamic rebel group al-Shabab, under a lockdown that started at 9 p.m. on Saturday. Most residents are staying indoors until the lockdown lifts on Monday morning.

The goal of a direct, one-person-one-vote election in Somalia, a country of about 16 million people, remains elusive largely because of the widespread extremist violence. Authorities had planned a direct election this time but, instead, the federal government and states agreed on another “indirect election,” via lawmakers elected by community leaders — delegates of powerful clans — in each member state.

Despite its persistent insecurity, Somalia has had peaceful changes of leadership every four or so years since 2000, and it has the distinction of having Africa’s first democratically elected president to peacefully step down, Aden Abdulle Osman in 1967.

Mohamed’s four-year term expired in February 2021, but he stayed in office after the lower house of parliament approved a two-year extension of his mandate and that of the federal government, drawing fury from Senate leaders and criticism from the international community.

The poll delay triggered an exchange of gunfire in April 2021 between soldiers loyal to the government and others angry over what they saw as the president’s unlawful extension of his mandate.

Somalia began to fall apart in 1991, when warlords ousted dictator Siad Barre and then turned on each other. Years of conflict and al-Shabab attacks, along with famine, have shattered the country which has a long, strategic coastline by the Indian Ocean.

AP journalist Rodney Muhumuza in Kampala, Uganda, contributed.

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source