Pope Francis backed him when he took on a president. Now he’s voting in the conclave

South East Asia correspondent

BBC/ Natalie Thomas

BBC/ Natalie Thomas“Not even in my wildest imagination did I think this would happen,” said Cardinal Pablo Virgilio David, describing the day he found out that he had been appointed a cardinal.

He was speaking to the BBC at his cathedral in Caloocan, on the outskirts of the Philippine capital Manila. He was leaving the next day for Rome to join the conclave, one of three cardinals from the country who will take part in choosing the next pope.

“Normally you would expect archbishops to become cardinals, but I am only a humble bishop of a little diocese where the majority of the people are slum dwellers, urban poor, you know.

“But I thought just maybe, for Pope Francis, it mattered that we had more cardinals who are really grounded there.”

Cardinal David has only been in the job for five months, after his surprise elevation last December. But in some ways he personifies the late pontiff’s legacy in his country.

Pope Francis had set himself the goal of bringing a Catholic church he believed had lost its common touch, back closer to the people.

“Apu Ambo”, as Cardinal David is affectionately called by his congregation, fits that mission well, having spent his life campaigning for the poor and marginalised.

The Philippines has the largest Roman Catholic population in Asia, nearly 80% of its 100 million people, and the third-largest in the world.

It’s one reason why Filipino Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle is believed to be a papabile, or frontrunner to replace Pope Francis – Tagle was also talked of as a contender in the last papal conclave 12 years ago.

The country is considered a bright spot for the Roman Catholic church, where faith is strong, its rituals woven into the fabric of society.

Yet the church is facing headwinds there. Its doctrines on divorce and family planning are being challenged by politicians, and newer charismatic churches are winning converts.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPope Francis helped restore morale in the Philippines church, though he did not offer answers to these challenges beyond being more welcoming of diversity and urging the clergy to be more responsive to the needs of the poor.

But those on the activist wing of the church did feel encouraged by his support.

For Cardinal David that support was critical when he faced his greatest test, during the war on drugs declared by former President Rodrigo Duterte in 2016.

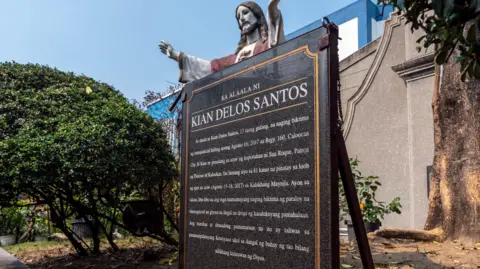

He took me to see a plaque he had erected in front of his cathedral in memory of Kian Delos Santos, a 17 year-old boy from his diocese who was gunned down by police in August 2017.

Kian was just one of many thousands who died in Duterte’s campaign – estimates range from 6,300 to 30,000. What made his case different from most was that the usual police justification, that he was armed and had resisted arrest, was contradicted by eyewitnesses and security camera videos.

The police officers had murdered him as he pleaded for his life. Three officers were eventually convicted of the murder, a rare instance of accountability in the drug war.

The cardinal is still visibly affected by the hundreds of killings that happened in his diocese – a cluster of low-income neighbourhoods typical of the areas targeted by the police in their notorious tokhang, or “knock and plead” raids, against alleged drug dealers and users.

BBC/Jonathan Head

BBC/Jonathan Head“It was just too much seeing dead bodies left and right,” Cardinal David says.

“And you know, when I would ask people what they thought, you know, why these people were targeted. They said they’re drug users. I said, so what? So what? Who told you that just because people use drugs, they deserve to die?”

He began offering sanctuary to those who feared they were on police hit lists, and then drug-rehabilitation programmes, in the hope this might protect them.

He also did something the church as a whole did not do for several months: he openly criticised the drug war as illegal and immoral.

As a result, he received many death threats. President Duterte accused him of taking drugs, and talked about decapitating him. The government also filed sedition charges against him, though these were eventually dropped.

In those difficult years Cardinal David found he had a powerful backer, in Rome.

On a visit to the city in 2019 Pope Francis had taken him aside to give him a special blessing, saying he knew what was happening in his diocese and urging him to stay safe.

When they met again in 2023, and he reminded the Pope that he was still alive, he says the pontiff laughed and told him: “You have not been called to martyrdom yet!”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe role of the Roman Catholic church in the Philippines has changed over its 500-year history in the archipelago.

It was closely associated with the Spanish conquest, Spanish friars acting as de facto colonial administrators and the church becoming a big landowner. When the US replaced Spain as the colonial ruler in 1898, enforcing a separation of church and state, the political influence of the Catholic clergy waned.

But the church retained the allegiance of most of the population; even today, after inroads made by charismatic protestant churches, nearly 80% of Filipinos identify as Roman Catholic.

Since independence in 1946 the church has had an uneasy relationship with power. Its deep roots and establishment status have made it an influential player, wooed by political factions but also needing their support to protect its interests.

Attitudes began changing in the 1970s and 80s, the time when a young Pablo David and many other senior church figures today were studying to enter the priesthood.

This was the era of “liberation theology”, which came out of Latin America and argued that it was the duty of the clergy to fight against the pervasive poverty and injustice all around them.

When then-President Marcos, father of the current president of the Philippines, declared martial law in 1972 and began jailing and killing his critics, some priests even went underground to join the armed resistance.

But the church hierarchy continued what it called “critical collaboration” with the Marcos dictatorship.

That changed dramatically in February 1986, when the then-Archbishop of Manila, Cardinal Jaime Sin, called on people to come out on the streets and oppose Marcos, sparking the famous “people power” uprising which deposed the president.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCardinal Sin would reprise that role in 2001 when he helped overthrow another beleaguered president, Joseph Estrada.

After that, though, church leaders were accused of cosying up to Estrada’s successor, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, partly to gain her support in opposing growing political and social pressure to expand access to family planning and legalise divorce.

And they were reluctant to condemn President Duterte’s drug war because, despite the appalling human cost, it remained popular with the Filipino public, at least away from the poorer areas where the killings took place.

Nearly 40 years after its pivotal role in overthrowing the Marcos regime, the church’s influence once again seems to be waning, as it did a century ago.

For instance, the Church’s fervent opposition could not prevent the Philippines Congress from passing the Reproductive Health Law of 2012 that made family planning easily accessible.

This is despite the fact that many Filipino Catholics remain conservative on issues like gender and divorce, says Jayeel Cornelio, a sociologist who has written extensively on Catholicism in the Philippines.

The church’s defeat over family planning, he says, is indicative of its diminished sway over national politics.

“The Catholic church was practically sidelined during the Duterte presidency. When Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos ran for president in 2022, many Catholic leaders and institutions expressed their dissent and even endorsed the opposition. But Marcos still won.”

BBC/Jonathan Head

BBC/Jonathan HeadMany Filipinos welcome this, including, it seems, Cardinal David.

“It is not the business of the church to govern, neither is it the business of government to run a church”, he said.

“But we can complement one another – I cannot say we will be apolitical. So long as we stick to our role as a moral and spiritual leader, we can give guidance, even about political and economic matters.”

Even that more limited view of the church’s proper role, though, has run into opposition.

Thirteen years after overcoming ecclesiastical objections to the Reproductive Health Bill, the Philippines Congress is now trying to get a bill passed which would legalise divorce, something else the church disagrees with.

“I do not expect them to change their official doctrine, but in my job as a lawmaker, I try to address the problems that Filipinos face, and I don’t want them to meddle in my work. It is against our constitution to legislate in favour of any religion,” says Geraldine Roman, the first transgender member of Congress in the Philippines.

A practicing Catholic, she credits Pope Francis with creating a more welcoming environment for LGBTQ+ people with his “who am I to judge” statement.

“Nobody misgenders me in my church now,” she says.

But she objects to the Catholic church lobbying against the divorce bill, which she argues will free thousands of Filipino women trapped in abusive marriages.

“The church is free to try to indoctrinate Catholics into sticking it out in their marriages. But in the end, it is the decision of the couple, and not even the church can meddle in that decision.”

BBC/Jonathan Head

BBC/Jonathan HeadOther challenges include a congregation which is increasingly disengaged. While the number of Roman Catholics has fallen only slightly in the past three decades, the number attending mass at least once a week has dropped by half, to just over one third of those surveyed recently.

Then there are the various scandals associated with the Catholic church, especially the sexual abuse of minors, which critics say Pope Francis, while he did tackle the issue, did not do enough to address.

Cardinal David recalled how President Duterte “loved to wave” a book called “Altar of Secrets”, an expose of alleged scandals in the Filipino church, and how he would say, “oh, those hypocrites. Don’t listen to them. They don’t practice what they what they preach. They are abusers. I must say some people swallowed it hook, line and sinker. So I am not surprised that our moral credibility has been challenged.”

But, he adds, defensiveness is not the way the Church can win back its credibility.

“It should be humility. As Pope Francis advised, dare to be vulnerable. Dare to be criticised. Try not to remain on that pedestal where people cannot reach you, show your humanity.

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source