Opinion | When a Supreme Court Justice Probably Endorsed Perjury

Now, here’s where things get a little fishy.

During the trial, the lawyer for the plaintiffs, former Attorney General Charles Lee, called on Madison to provide the commissions to the court or at least confirm their existence. He refused. He asked the (Jeffersonian) Republican-controlled Senate to provide a written record that Marbury and his co-plaintiffs had been confirmed. It refused. He called on the State Department’s chief clerk to testify, but he had what Paul calls “a convenient lapse of memory.” Finally, Levi Lincoln admitted to having seen a stack of commissions sitting on his desk on the day he took office on an interim basis (March 4, 1801), but he could not recall whether he saw Marbury’s commission and could not say what had happened to the rest of the commissions either.

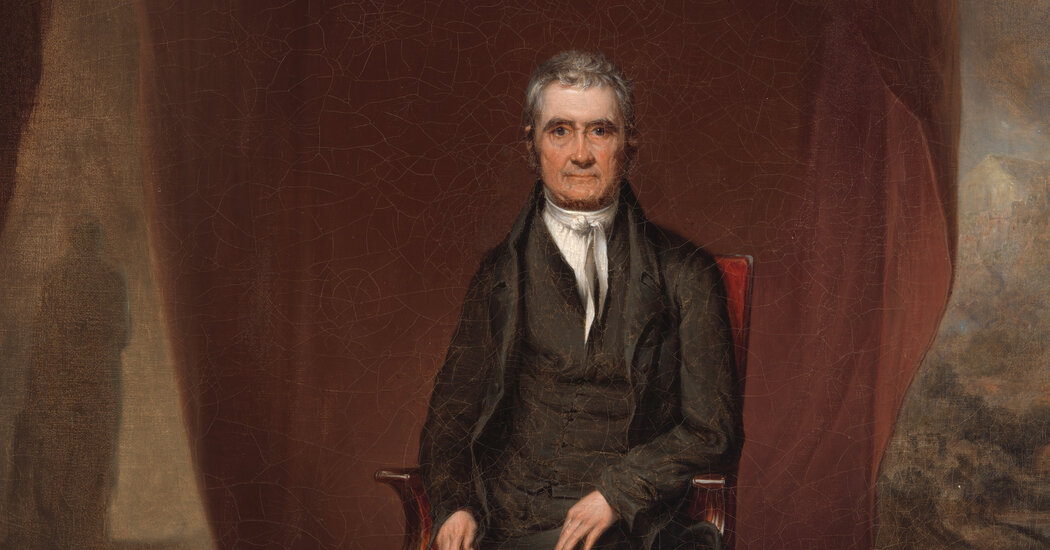

There was only one person on the court who knew exactly what had happened, and that was Chief Justice John Marshall. But he was presiding over the trial and could not testify. And so it was his brother, James Marshall, who told the court, in a signed affidavit read by Lee, that “he was called to the State Department and asked to deliver the commissions of the justices of the peace in Alexandria.”

James’s testimony was the only evidence at trial that the commissions had in fact been issued. And, Paul argues, it was “most likely a total fabrication.” In this telling, James Marshall perjured himself, and John Marshall not only let him, but may have even asked him to.

In his book, Paul argues that this was necessary, that Jefferson and his Republican Party were threatening the independence of the judiciary and that Marshall believed the ends justified the means. As Paul puts it, “Jefferson and the Republicans had left Marshall no choice by refusing to respect the court’s orders to provide proof that the commissions were signed and sealed. The lie bridged an evidentiary gap by establishing in court the existence of the commissions, which the whole world knew was true.”

Be that as it may, it’s still wild that the case appears to have turned on an act of perjury, facilitated by the chief justice, who then ruled in such a way as to assert and establish the authority of the court over the meaning of the Constitution. It should probably be said as well that in Paul’s view, Marshall essentially fabricated the conflict at the heart of the case, which is whether the Supreme Court could issue a writ of mandamus commanding Madison to deliver Marbury’s commission. Under the Judiciary Act of 1789, which established the federal judiciary, the court could do just that. But according to Marshall, Article III of the Constitution did not grant the court “original jurisdiction” to issue writs of mandamus, meaning that part of the law was unconstitutional.

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source