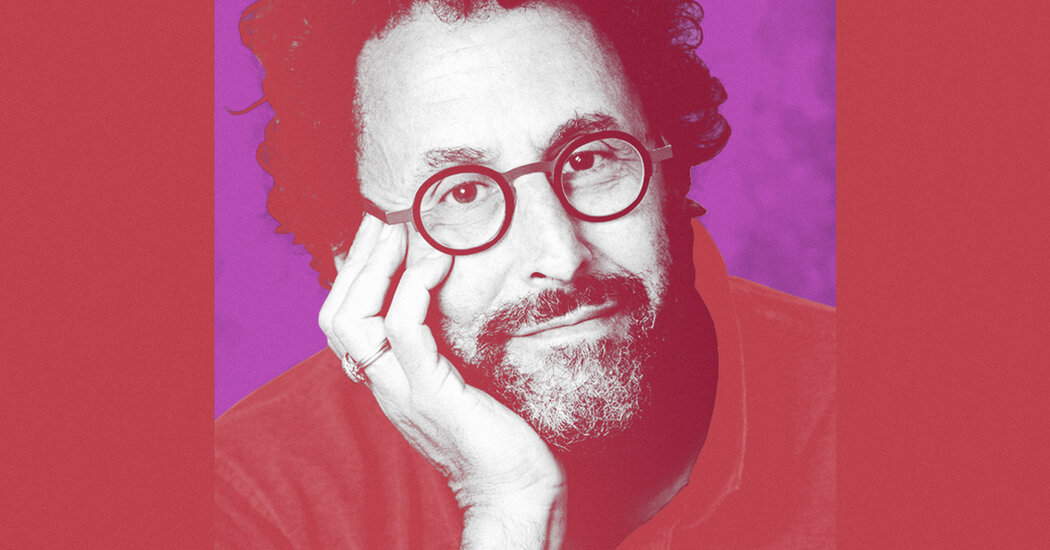

Opinion | Tony Kushner on the Republican ‘Fantasy’ of a Nation Controlled by ‘Straight White Men’

When you walk in a room, do you have sway?

I’m Kara Swisher, and you’re listening to “Sway.” Like a lot of gay people who came of age during the AIDS crisis, I’ve lived through decades of struggle and then real progress on gay rights. So it feels a bit like a deja vu nightmare these days, as the hard-won ground seems at risk, from Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” law to a contentious Texas effort that threatens to split up trans kids from their parents, it feels like we’re hurtling back to a less tolerant time we all thought we’d left behind long ago.

So I decided to talk to one of my favorite cultural icons, Tony Kushner. The Tony Award-winner’s 1991 play “Angels in America” wasn’t just great art, it also changed the entire conversation around AIDS and around the gay community. It’s set in New York City in the 1980s and follows the lives of people affected by the AIDS crisis. One of the characters is a gay Mormon man in denial. Another is Roy Cohn, a closeted Republican who was close to the Reagans and ironically was a major mentor to Donald Trump.

The play has stood the test of time, with an Emmy-award winning series on HBO in 2003 and a hit Broadway revival in 2018. But its message may be in danger. So I wanted to ask Kushner about how far the nation has come or hasn’t since “Angels.” And I also wanted to dig into some of his newer projects, including his recent remake of “West Side Story” with his old pal Steven Spielberg.

Tony Kushner, welcome to “Sway.”

Thanks. Nice to be here.

I don’t want to necessarily go back to everything you’ve done. I know one of the things you said was that, when you die, that “Angels in America” would be on your obituary in The Times, but you said, I will have an obituary in The Times, which I thought was pretty funny. But I’d love you to reflect on how it connects to today, especially in this moment when Ron DeSantis just signed the don’t say gay bill.

I don’t know exactly how to explain it. I mean, maybe just because it’s so long and there’s so much sort of stuffed into it. “Angels” always seems to have some kind of connection to whatever historical moment it’s being revived in. But I don’t know that ultimately that’s the greatest power that it possesses. I think it’s a more indirect power that speaks to issues that human beings are constantly dealing with.

They’re not not-political issues, but they’re a mixture of political and personal and psychological and philosophical and theological issues. And I think that the stuff in the play that I’m proudest of is the stuff that speaks to that. And, you know, it’s not a surprise to anyone that the rights of minorities and human rights in general are not guaranteed. It’s Passover, so we can say it. In every generation, the pharaoh arises to destroy us. Many times within each generation, the possibility of enslavement, of oppression, of destructive, murderous discrimination exists and has to be resisted.

So, you know, we’ve made immense progress since “Angels” first appeared. And yet we are not saved. I mean, there’s no permanency to it. This bill in Florida is an abomination. It’s cynical. And I think it exists primarily, as so much the sort of insane right-wing legislation all over the country now exists, to hopefully drive these issues back into the Supreme Court, where this very right-wing court may or may not dismantle everything that’s been gained.

There’s something you said once, that there’s not such a thing as permanent win in the political arena or undoable progress. And yet, at the end of “Angels in America,” you know, the world only spins forward. But it doesn’t necessarily spin in the way you’re talking about there. You’re talking about progress, correct?

Well, yes. I mean, that is a part of the vast damage done by reactionary politics is that the world is spinning forward. Change is happening. People are progressing. I mean, you can’t reverse the flow of history. The white, straight, theocratic right is so determined to return the country to some fantasy of exclusive control by white straight men, it is that, it’s a fantasy. But when they try to enact it into legislation like DeSantis did, it creates damage precisely because, while they’re fighting against the tide of history, it’s continuing to move forward. And the price of that friction of their insistence on attempting to reverse the flow of history are human lives. There’s an unspeakable cost to it in pain. So I believe that there is a kind of forward momentum —

Mm-hmm. But it might not be a positive forward momentum, in other words?

Well, it’s always positive. I mean, Brecht said this great thing. The bad new things are always better than the good old things. So I think we have to keep aware of the fact that we’re moving forward and yet also be aware that, while we’re moving forward, there’s a lot of mischief that can be made.

For instance, these terrible people in Florida, what they’re really after, obviously, is not really about not teaching kindergartners about, you know, gender. What they’re really worried about, what they’re really after is same-sex marriage and adoption. But you can imagine the horrific situation that would result if they actually got the Supreme Court to reverse the decisions that have made same-sex marriage law across the United States.

OK, so “Angels in America” is set at a very specific time, during the AIDS epidemic and the Reagan years, which you wrote it after that. But it is rather prescient. Roy Cohn is one of the main characters.

For people who don’t know, he was the ruthless right-wing lawyer who was Joseph McCarthy’s chief counsel. He was homophobic, closeted, ended up dying of AIDS in 1986. He was also one of Donald Trump’s mentors.

And I think when I was watching that play, I was thinking, oh, he’s obviously the articulation of Reaganism. But in fact, it was something much worse, which was Donald Trump. I can’t believe I’m saying much worse, but there you have it.

Well, you’re making a separation that I don’t agree with. I think —

OK, tell me.

I think Donald Trump is the inevitable consequence of Reaganism.

Well, let’s talk about that first then, because it just feels like, even more so, Roy Cohn’s resonance is even deeper now. But go ahead.

Yeah, well, yes, I mean, because the kind of McCarthyite demagoguery where Roy Cohn honed the skills that he then passed on to Trump were held in check for years by holdovers from the old Republican party that wouldn’t have tolerated the sort of behavior that became the daily diet of the Trump administration.

But that was because they were more genteel. They believed that the Senate was a debating club, blah, blah, blah, blah. It took a while. It took 40 years for Reaganism to really do the damage that it was intent on doing at the beginning.

And a lot of the people, including Reagan himself, would never have recognized themselves in Trump. And a lot of these sort of — I mean, God bless them. The never-Trumpers, the Republicans who said, I’m against this, this is a terrible visitation on the Republican Party, they didn’t recognize what they’ve done. They don’t recognize themselves in Trump.

But ego-anarchism, which is what they were always talking about — I mean, what does anarchism lead to except lawlessness? What does it lead to except, you know, people who flagrantly decide that it’s up to them whether or not they obey a congressional subpoena or obey the Hatch Act or any other law that isn’t convenient to them?

So one of the things that’s really striking is when you look at the way you wrote Roy Cohn. Do you see anyone today that resonates in the same way? Because you see his influence everywhere.

Yeah, I mean, I think when Trump has lamented, where’s my Roy Cohn, I think he’s not just speaking in general, where’s a lawyer? But instead of Roy Cohn, he got Rudy Giuliani, who’s batshit. I mean, sorry, bananas. Can you say batshit?

You can say batshit, please.

Anyway, I mean, whatever Giuliani was. At one point, he was a reprehensible human being but at least coherent. He’s now become completely embarrassingly incoherent. And if he had anybody who really loved him, they would find some way to get him to leave the public arena.

You know, I think that when Trump said where’s my Roy Cohn, I don’t know. I’m sure there are people like him. But every time one of these new, sort of really smart — ostensibly really smart — Trump lawyers pop up, they pretty quickly disintegrate into self-serving babble. And Roy was of great service to people like the Reagans. He really knew how to do the job that he was assigned to do.

Instead of that, I think you have sort of clowns like Roger Stone or Bannon. I mean, these people are show-boaters.

So in the interview about “Angels in America,” you said, quote, “The play doesn’t describe a time of great triumph. It describes a time of great terror, beneath the surface of which, the seeds of change are beginning to push upward and through.” How do you assess where we are right now? Do you think the seeds of change in that positive way you were talking about are there now? Or is it a different time?

Oh, absolutely. I mean, and there’s the kind of grim — I mean, and this is one way in which the world continues to spin forward, even though there are efforts to get it to reverse direction. The murder of George Floyd forced the country, for a number of seconds anyway, to pay attention to what’s happening to young Black people, to Black people in general at the hands of the police. And it caused a conversation about systemic racism, about structural racism, about the endurance of racism as like a continuing thread throughout American history and that is still, even though we’ve now had a Black president, we’re still you know, so far from where we ought to be as a democratic society.

And it was used to push back and win political gains too with critical race theory in Virginia, for example.

Oh, well, and they’re trying to do that now. Yes, and in Virginia, it succeeded. But I see so much evidence that the conversation that got started is not going to go away. And I believe that — I mean, the example of George Floyd is something of a truly monstrous event. I mean, what was so extraordinary about the immediate aftermath is that, in the middle of a pandemic, when you could feel people like Trump trying — I mean, you could hear him trying very hard to say, oh, this is all going to be about rioting and looting. And the country as a whole, because of the insistence of the Black community, resisted that, for a time at least.

For a time.

Yeah, but I think for a significant time. I mean, I think it felt to me very much like the moment when AIDS first appeared in the ‘80s. And it was a sexually transmitted disease that killed gay men. So people like Falwell and people like that, William F. Buckley, jumped on that and said, here it is. It’s God’s revenge on you for doing these disgusting things.

And the L.G.B.T. community could absolutely have kind of cowered. And instead of that, there was a determined insistence that we grab hold of the narrative and make this biological catastrophe that was happening not a cause for retrograde motion, not a cause for us losing rights, but actually, we insisted that this was one reason why, among many reasons why, people had to look at what happens when people are oppressed. And I think that the same thing happened after the George Floyd murder. So I think that there was an insistence that the narrative continue to go in a progressive direction. And I believe it was one. I mean, I think critical race theory nonsense from the right, it’s desperation. It’s you know —

Well, Tony, it works.

It works if we let it work. But I don’t think that we — I mean, that’s the thing is that, yes, it will absolutely work if we start to cede ground. I mean, if the Democratic Party listens to too many people saying, oh, we have to now become more centrist, by which they mean, don’t talk about Black people anymore. Don’t talk about L.G.B.T. rights. Don’t talk about trans people anymore.

Biden’s campaign was a tremendously progressive campaign. It took a lot of work to make him adhere to that. And I think that we need to keep going in that direction. If we do, if we collectively fight back against nonsense canards like, oh, they’re going to teach your kids to be unhappy that they’re white or whatever the hell it is they’re saying or they’re going to teach your kindergartner —

They’re using the term parental rights on all these things, whether it’s critical race theory — but the numbers are big, the anti-L.G.B.T.Q.+ bills have been increasing since 2018. There’s different estimates, but around 200 state bills have been proposed so far this year. Many target transgender rights specifically, some with athletes, which is a way in. They did the same thing around abortion. They targeted small areas and then moved on. How do you look at these bills? And why are they particularly targeting transgender rights at this point?

Because I think that — I mean, it’s not OK now, kind of not OK. I mean, Marjorie Taylor Greene just tried it with Pete Buttigieg and his husband. It’s not really OK to sneer openly at gay men and lesbians. So they have to find somebody that they can make miserable and laugh at. And as long as they present a grotesque caricature of what trans people are and what trans people want, yeah, they can get everybody in a state of hysterics.

An understanding of the trans movement requires confronting something that, even though it’s not new — I mean, trans people are not new. We’ve had trans people in our society for as long as we’ve had a society. But an articulation of what gender is that the trans community is articulating, that requires a confrontation with something new and unfamiliar. And you have a choice then. Do you dive in and try and really wrap your mind around it, or do you run screaming in the opposite direction? I mean, I can’t remember his name, the governor of Utah.

It’s Spencer Cox. It’s Spencer Cox.

Right, who wrote that extraordinary letter, explaining why he was going to veto the Utah anti-trans bill. I mean, that letter is — if people haven’t read it, you have to read the whole thing. It will make you cry. It’s so deep. And it’s written by a Republican.

And as Cox pointed out in that letter, the number of people, of trans girls who want to compete in women’s sports is minuscule. I mean, it’s nothing. It’s like a tiny fraction. And so you have to ask yourself, am I willing to destroy the lives of thousands of trans girls over this pretend crisis which is not a crisis at all?

The most moving statement in that letter was when he said, I don’t want these people to die. I want them to live.

Yeah, absolutely. But let me play back something from you, one of the characters in “Angels,” Lewis, goes on a mini-rant about tolerance. Let’s hear a clip from the National Theater production. Lewis played by James McArdle.

- james mcardle

-

That’s just liberalism, the worst kind of liberalism, really, Bourgeois tolerance. And what I think is that what AIDS shows us is the limits of tolerance, that it’s not enough to be tolerated, because when the shit hits the fan, you find out how much tolerance is worth, nothing. And underneath all the tolerance is intense, passionate hatred.

So that was something to write.

Yeah, he’s right. And —

Well, you wrote it. You wrote it.

He’s also saying it to a Black drag queen who has some questions about it and also doesn’t need to hear it sort of explained to him in the way that Lewis is doing. But I don’t think that what Lewis is saying is in any way contradictory to what I’m saying. I mean, tolerance is, of course, intolerable. Tolerance means that you accept a position of a second class citizen, of a power imbalance. And you rely on the kindness of those in power to let you go about your life.

And that is not actually what any kind of constitutional democracy can offer its citizens.

So what matters would be power then?

Well, power as always. Of course, that’s the name of the game. I mean, it’s power. But you know, it’s the way that power is handled. What matters is equal protection under the law, the 14th Amendment, and everything in the Constitution that guarantees a rule of law and that everybody is treated equal under the law in the United States.

So do you think that specific kind of tolerance has changed at all since you first wrote “Angels?” That people still acquiesce to this?

Well, I think that it’s always — I think that there’s a paternalism. This is the conservative stance. You’re asking for too much. Everything worked fine before. We didn’t bother you so much. You could do the things you want to do.

Why so loud? Why so loud?

Why so loud? Why so upset? Why so angry? And that, again, goes back to what I was saying earlier. If you start to think for a minute why somebody would really care about marriage equality or why somebody really would care about some sort of control on police, you think about what life is like for somebody who lives under these kinds of forms of oppression.

And then you start to get into trouble if your whole worldview is predicated on pretending that everybody could be happy if we just left it up to Donald Trump to run things.

Right. It’s the sort of relying on the kindness of strangers is not particularly good, to quote Blanche Du Bois and Tennessee Williams.

And in “Angels in America,” Pryor says to Hannah, I’ve always depended on the kindness of strangers. And she says, well, that’s a stupid thing to do. I actually love that line. But I mean, Tennessee was talking about a glue that holds the human community together that is, I think, a political issue. But it’s also other things as well.

Do you think that glue is irrevocably broken at this point? Because —

No.

— actually, the angriest people are not on the progressive side, whether it’s the people’s convoy or the truckers in Canada or Russell Brand on any given day or Joe Rogan. The angriest people are not on that side anymore, it seems like. Or perhaps everybody’s angry. I don’t know.

Well, I mean, I think there’s a complicated anger on the left, on the progressive side. I mean, presumably, people on the progressive side of things believe in the possibility of constructing a more just world. And that’s going to take a lot of thinking as well as a lot of feeling.

For people who are essentially interested, I mean, in a kind of nihilism right now, of just tearing everything down, those people don’t need anything other than anger.

I absolutely do not think that these bonds, what Lincoln called the mystic chords of memory, the bonds of affection that hold — that held the union together, I don’t think they’re broken irrevocably. I think it’s always been the sort of secret of democracy that it depends on a kind of secular religion. And the religion is the union.

I mean, that was what Lincoln knew. That’s what made him so immensely effective during the Civil War. And for a long time, we’ve held on to an understanding of that. But the union can only cohere if people are believing that what they’re promised in the Declaration is still possible, life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

So you’re not worried about that?

Oh, I didn’t say I’m not worried. I’m very, very worried about it. I mean, democracies are vulnerable. And they can fragment.

We’ll be back in a minute.

If you like this interview and want to hear others, follow us on your favorite podcast app. You’ll be able to catch up on “Sway” episodes you may have missed, like my conversation with Andrew Garfield. And you’ll get new ones delivered directly to you. More with Tony Kushner after the break.

Let’s talk about the new adaptation of “West Side Story.” Steven Spielberg was the director and apparently had to coax you into writing the screenplay.

Yes.

Talk about why you wanted to do this, because you were working on a lot of different things at the time.

Well, I love working with Steven. This was our third movie together.

Yeah, “Munich” and “Lincoln?”

“Munich” was the first, “Lincoln” and then “West Side Story.” And now we’ve made another one that will be opening this fall that we co-wrote. I love working with him. I think he’s — this is not a word — I don’t use the word genius very often. But I think Steven is actually a genius. I think that there’s a level of ability that is, certainly for me, completely sort of awe-inspiring and confounding.

And he’s a mensch. I mean, he really cares about things that I think decent people need to care about.

Why did he pick this? You were working on something else, right, that was more difficult?

Well, we were working on a couple of things. And they’re not dead. But Steven calls the shots. We were working on that part of it. He decided he wanted to make “The Post” And then he felt very strongly after “The Post” that it was time to make “West Side Story.”

And I think it probably, even though Puerto Ricans are not immigrants to the United States because they’re American citizens, the xenophobia that was being generated by this sort of ginned up immigration crisis that Trump ran on and the sort of hideously terrible job all over the planet that countries are doing in terms of taking care of migrant populations, refugee populations, I think it bothered him and upset him. And he’s always wanted to do “West Side Story.” And it suddenly seemed him, this would be an interesting way to speak to this political moment. I mean, I don’t know that he thinks quite that literally. He has a gut instinct. And his gut instinct over and over again has been pretty great.

Right. So something that struck me is that neither gang, the Sharks or the Jets had any real power. There’s an early scene when the police break up the fight and say their rivalry is pointless.

- speaker 2

-

I realize if any of you helps me out, you might spoil your chance to murder each other over control of this earthly paradise.

- speaker 3

-

Jets control it, and you know it.

- speaker 2

-

Oh, yeah. But golly gee, Balkan, not according to the New York City Committee for Slum Clearance, which has decided to pull this whole hellmouth down to the bedrock. And you’re in the way.

Can you talk about that? That was — you all brought that out much more so than in the original.

I’m very interested in any kind of situation where there’s a sort of zero-sum economy.

So they’re fighting over nothing?

They’re fighting over nothing. And they’re fighting over nothing to the advantage of people who want them to fight over nothing. I mean, the blight of urban poverty was referred to, often by the Committee for Slum Clearance, as a reason why we needed to wipe out these neighborhoods and put up high-rises.

And there were people whose interests this served. And I mean, this is another Bertolt Brecht thing. He says the solidarity of the oppressed for the oppressed is the world’s one hope. And I think he’s right. If groups that are fighting for emancipation, for liberation, for an end to oppression an end to racism, et cetera, don’t make common cause with each other, if you’re a minority, you’re doomed. I mean, your only hope is to form communities with other minorities and fight for the liberation of all.

I mean, that moved me a lot. And I think it’s inherent in the original “West Side Story,” but not made as explicit.

Right. Now, the movie got a good reception. The box office was lighter than I think you all expected. But Arianna DeBose won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress in the role as Anita. She’s astonishing. The movie also got a Best Picture nomination. There were also critics, I know you’re aware of them, who argued they didn’t need the remake of “West Side Story.” And no amount of updating could save the story’s depiction of the Puerto Rican experience.

Do you think the criticism is valid? I know The Times had a piece.

At least five or six in The New York Times.

So talk a little bit about that.

I don’t have any objection to somebody disliking work of mine. I probably won’t agree with them. But our “West Side Story” is very, very different from the 1961 film and the 1957 musical. It is absolutely recognizable. I don’t think that the ‘61 film or the ‘57 musical actually resemble what these people are claiming.

I do not believe, I vehemently disagree with anyone who says that the original “West Side Story” is anti-Puerto Rican, that it shows Puerto Ricans as being animalistic or knife-wielding thugs. I mean, it’s nonsense. It’s just literally not true. Go read it. You know — go look at the original material.

And Bernstein and Arthur Laurents and Stephen Sondheim, they were progressive people. I mean, did they think that the Sharks and the Jets were two exact sides of the same coin? No. There’s nobody being racist about white people in “West Side Story.” The racism is coming from the Jets. It’s the Montagu-Capulet model that’s created this misunderstanding about “West Side Story.”

My high school did an unfortunate pairing of the two one year where they did —

Yeah, that’s happened a lot.

Oh, yeah, it was unfortunate, I would say.

I mean, Shakespeare intends that you don’t know the difference. The only way to remember which one which is that Juliet rhymes with Capulet because his point is this violence is utterly meaningless. It’s just an old feud, whereas Bernstein and Sondheim really wanted people to think this is coming because of xenophobia. It has a cause, you know.

Were mistakes made in ‘57? Yes. Were they correctable without doing a complete overhaul of the material? I feel absolutely.

And I can also say the thing that people always say and they shouldn’t say, which is, yeah, well, I know at least as many Puerto Ricans, in fact, you know, many, many, many, many, many multiples of Puerto Rican people who have told me that they loved “West Side Story.” They wept watching our “West Side Story,” as have written Op-Ed pieces in The New York Times. But anyway —

Did you worry about doing this? Because you talk a lot about being able to write characters, even if you’re not a character, you’re not that person.

Yeah. I absolutely believe that one of the pleasures of art is that you get to go and hear the way another person has imagined people who are not like him, her, or themselves. Did Shakespeare really understand Jews the way that one would have hoped he did in “Merchant of Venice?” Absolutely not.

Are there parts of “Merchant of Venice” that are anti-Semitic? Yes. Do I wish Shakespeare hadn’t written it? No.

And I’m interested in how the person that I would say is probably the greatest genius ever to put pen to paper — it’s interesting to me to see the limitations of his vision as well as his extraordinary insight. So I know that what I’m seeing is a fiction created by somebody when I go to the theater or when I go to a movie, when I read a novel.

I know that this is not real. It’s pretend. And even when I watch a documentary, I know that documentaries are, of course, in some ways, they’re artificial constructions. You hope they’re telling the truth, but you have to be a little skeptical about that as well. You always have to be skeptical about the truth. So my feeling is, you know, I absolutely think that there is an enormous problem with equality of opportunity for screenwriters of color, for women, for trans people. It’s much easier for a Jewish guy like me to get work than it is for, let’s say, a Puerto Rican man or woman. But that problem is a problem with economics and a problem of employment practices and a problem of a determination to make a more diverse and representative industry.

But do you worry about things you could write, that you could write at all? Is that something you think about?

You mean worry like should I not do it?

Yeah. If you had done anything differently on that production, for example, would you looking back now with “West Side Story?”

You know, actually with “West Side Story,” no. I stand by my original feeling that “West Side Story” is a great work of art. And I feel no shame whatsoever in saying that I love it. And I think it was worth redoing it.

I think you always have to ask yourself whether or not you are capable of understanding a situation well enough to do a good job writing it. One of the nice things about being a screenwriter or a playwright is that when I write a character like Valentina, the character that Rita Moreno plays, Rita Moreno is going to play that character. And I’m going to listen, and Steven listens to what Rita Moreno has to say about that character.

In my musical “Caroline or Change,” the main character is a Black woman in 1963 in the town that I grew up in and Lake Charles, Louisiana. I was nervous as hell about writing it, of course. I think I did a really good job with it. I also knew that George C. Wolfe was going to direct it. George is Black, completely brilliant man. And Tonya Pinkins, this incredibly great actress, was going to play it.

And so I know that, you know, Tonya is going to say, I don’t think she would say this, or I don’t think it would happen this way. And George would say that, and they did. And I think they would both say I responded to that.

I mean, I think if I can just say this, the really important thing is that we make sure that there are equal opportunities of employment. We should want an art that represents the world, not just one point of view. And also, if I write a Black character and you go to see it, I want you to know that it was written by a gay Jew. If I go to see a movie with a Black character or a Puerto Rican character written by a Black person or a Puerto Rican person, I’m going to know that that’s who wrote it. And that’s going to have an effect on how I look at it.

Being an audience requires work. It requires sophistication.

OK. You’ve collaborated with a ton with Spielberg, as you said. But your late friend Larry Kramer said a few years ago that he’d wished you go back to writing plays. I would agree with him. When are you going to come back to Broadway? What would it take for you to do that?

I want to go back to writing. I mean, I am working on some plays. I’m a very slow writer. And I’m working right now on two miniseries for television.

That’s not a play.

I know. But I’m always working on a play at the same time. So I have a couple of things that are in process. And I hope I’ll have one of them ready fairly soon. It may or may not be on Broadway. Broadway is only a small aspect of theater, of course.

Right, obviously. But in theater — does it just not interest you as much, the theatrical experience?

No, no, theater is my first — aesthetically speaking, my first love. And it’s what I really should be doing.

So why aren’t you? Only because I was a beat reporter. And I don’t do that anymore. And I don’t want to do it anymore. I don’t like it. Everyone’s like, you should do that. You’re so good at it. I’m like, I don’t want to. I want to do this or something else. So what’s happened here is that you don’t —

You know, for all sorts of reasons, I got interested in writing film. And I found somebody that I really loved writing film with. But I’ve always had this nightmarish image of sitting by a pool in L.A. saying, I’m coming back to the theater next year, and then I drop dead, and I never have done that. I really want to.

You’re not sitting by a pool right now, right?

I’m really not. I’m in my apartment in New York, dying of dust allergies, because I have too many books.

So what play would you write? People are wanting a play from you. Is it the Trump play? It’s been a couple of years.

I’m working on the Trump play. It keeps changing and changing and changing.

Is it a Trump play, or you’re just going to call it the Trump play? Is it about Trump?

It’s not — well, I won’t say anything more about it. It’s definitely about the family and sort of about Trump. But it keeps becoming about other things.

Well, he is about other things, isn’t he? He’s not about just —

Yes, he is.

But you want to examine him? Because one of the things you said about “Angels in America” was, I don’t know if that kind of work is best done as an immediate response. Obviously, many people were very emotional during the Trump era. Do you think you need more time? Or is there a theme coming out of this, of the Trump era?

Oh, yeah. I mean, well, what he’s done, I mean, his entire — not Trump himself, but to an extent Trump himself and then everyone around him, I mean, these are bottom-feeders who devote enormous amounts of time and some intelligence and vast resources to finding all the weak spots in American democracy. I mean, so in a time like that, democracy is thrown up into a crisis. I mean, this is something that many people have said. But when Lincoln says in the Gettysburg Address, fourscore and seven years ago, our forefathers brought forth into this continent a new nation conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal, it’s a proposition. And it’s always the case that democracy, like theater and like art, democracy lives in a state of crisis. And we’ve been thrown into a profound crisis.

So is there a name? Do you have a name for the play?

I do have a great name for it, but I can’t tell you.

Come on! What is it?

No, it would give it away.

Really?

Yes.

You have such long names for your plays. Is this long?

No, this is just one single word. But it would give away too much.

Oh, really?

Yes.

When do you imagine it being mounted?

I don’t know. Don’t ask me that.

Well, don’t do miniseries. Stop with the mishegos.

Why don’t you go back to beat reporting, you’re so great at it?

Sway is a production of New York Times Opinion it’s produced by Nayeema Raza, Blakely Schick, Daphne Chen, Caitlin O’Keefe and Wyatt Orme with original music by Isaac Jones, mixing by Sonia Herrero and Carole Sabouraud and fact-checking by Adam Schival and Kate Sinclair. Special thanks to Shannon Busta, Kristin Lin and Kristina Samulewski. The senior editor of Sway is Nayeema Raza, and the executive producer of New York Times Opinion audio is Irene Noguchi.

If you’re in a podcast app already, you know how to get your podcasts, so follow this one. If you’re listening on The Times website and want to get each new episode of “Sway” delivered to you poolside in L.A., download any podcast app, then search for “Sway” and follow the show. We release every Monday and Thursday. Thanks for listening.

[MUSIC]

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source