I’m Still Here brings Brazil’s dictatorship past to the surface

Tessa Moura Lacerda

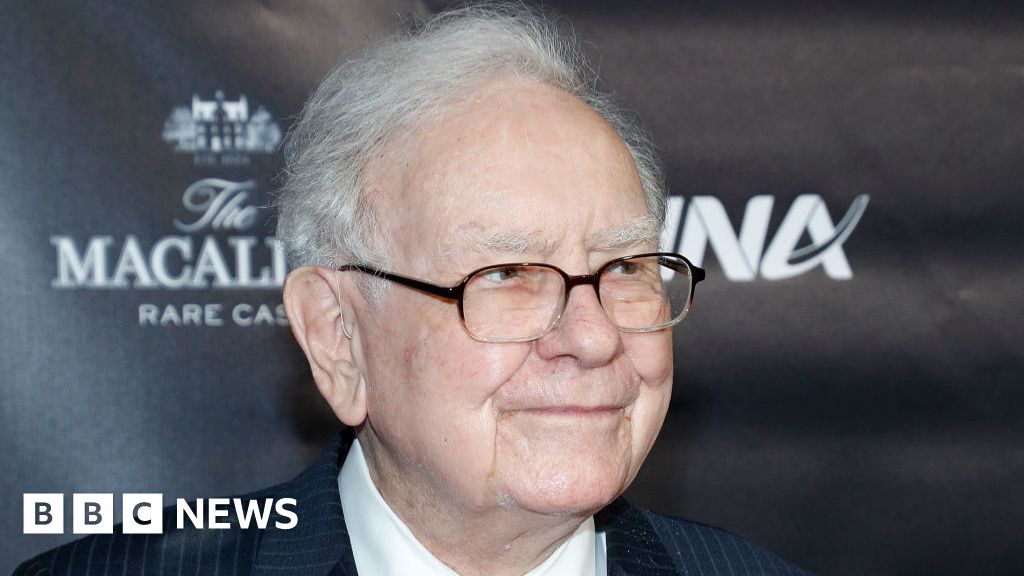

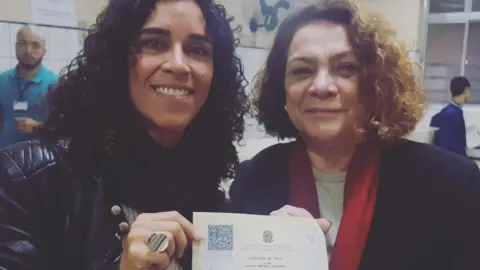

Tessa Moura Lacerda”Have we really done it?” Tessa Moura Lacerda asked her mother, in disbelief, as they stood outside a government office on a rainy August morning in 2019.

In their hands, a document they fought for years to hold – her father’s death certificate, now correctly stating his cause of death.

It read: “unnatural, violent death caused by the State to a missing person […] in the dictatorial regime established in 1964”.

Tessa’s father, Gildo Macedo Lacerda, died under torture in 1973 at just 24, during the most brutal years of Brazil’s military dictatorship.

Over more than two decades, at least 434 people were killed or disappeared, with thousands more detained and tortured, a national truth commission found.

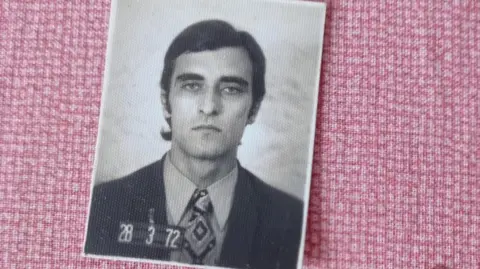

Tessa Moura Lacerda/Family handout

Tessa Moura Lacerda/Family handoutGildo and Mariluce, Tessa’s mother who was pregnant with her at the time, were arrested on 22 October 1973 in Salvador, Bahia, where they lived in fear of persecution.

They were part of a left-wing group that demanded democracy and sought to tear down military rule.

The dictatorship targeted opposition politicians, union leaders, students, journalists and almost anyone who voiced dissent.

Mariluce was released after being questioned and tortured, but Gildo disappeared.

He is believed to have died six days after their arrest, at a military facility in the nearby state of Pernambuco.

Former detainees told the truth commission they saw Gildo at the prison, being taken into an interrogation room from which they could hear screams that kept them up at night.

The commission also found documents citing his arrest.

But newspapers at the time reported that he had been shot on the street following a disagreement with another member of his political group.

The government would routinely plant false narratives in newspapers read by huge audiences in Brazil and internationally.

Gildo’s original death certificate, issued after a 1995 law allowed families to request the document for the missing, left his cause of death blank.

His remains, thought to be in a mass grave with those of other political dissidents, have never been identified.

’It’s like I can remember his fear’

Tessa, who never got to meet Gildo, said her father’s death had been a constant presence in her life.

Growing up, her mother gradually told her more and more about him until she was old enough to learn the brutal details of how he died.

But the lack of an official acknowledgement, and the fact that the family never got to bury him, had a deep impact on her.

”His absence, the absence of his body, brought a series of questions,” Tessa told BBC News.

”As a child, I thought that maybe he hadn’t died. I had this fantasy that he had managed to escape, that I’m not sure my mother even knew about.”

Now, as an adult, she said she still feels that there is something “broken” inside of her.

For years, she experienced nightmares, couldn’t sleep in the dark, and when she became a mother, struggled with panicked thoughts that something would happen to her children.

”It’s like I have a corporal memory of this fear,” she said.

”People may find it strange, like something supernatural, but it’s not.

“It’s trauma. I was born with it.”

Tessa Moura Lacerda/Family handout

Tessa Moura Lacerda/Family handoutUntil the age of 18, Tessa’s own birth certificate didn’t list Gildo as her father, with the family having to go through a lengthy legal battle to prove that he was.

This made the correction of her father’s death certificate an even more important endeavour.

”It’s part of my duty fulfilled,” she said.

”It’s not just for the memory of my father, but in the name of all others who disappeared, were killed or tortured during the dictatorship.”

In December, Brazil announced it would rectify the certificates of all recognised victims to acknowledge the state’s role in their deaths.

Until now, only a few families like Tessa’s had been able to work with a special commission, which was dissolved in 2022 by the president at the time, Jair Bolsonaro, and reinstated by President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in 2024, to have their certificates amended.

”It’s a legitimate settling of accounts with the past,” the head of Brazil’s Supreme Court, Luís Roberto Barroso, said.

Tessa Moura Lacerda/Family handout

Tessa Moura Lacerda/Family handoutIn recent weeks, a national conversation has been sparked over this violent history after a new film by BAFTA-winning director Walter Salles brought the realities of the dictatorship to the surface.

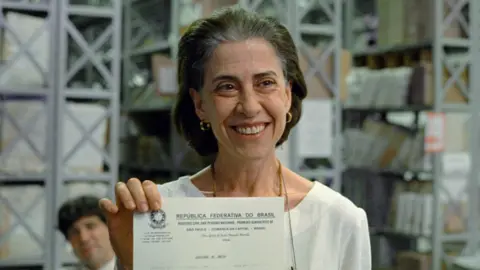

I’m Still Here, based on a book with the same name by Marcelo Rubens Paiva, tells the story of the author’s mother Eunice and her fight for justice after his father, former congressman Rubens Paiva, was tortured and killed.

Eunice waited 25 years for her husband’s death certificate.

She had no access to the family’s bank accounts without it, and had to rebuild her life.

She died in 2018 without knowing exactly what happened to her husband in his last hours, and without being able to bury him.

Fernanda Torres, who plays Eunice in the film, won Brazil’s first Best Actress Golden Globe Award last week for her part in the film – and many are hoping to see her on the list of Academy Awards nominations later this month.

She told BBC News she had huge admiration for Eunice.

“She is a woman who never spent a second of her life seeking recognition for herself… She wanted the death of her husband to be recognised.

“Despite the world changing, that absence was never cured,” she added.

“How are you going to tell these families: ‘Just forget. Brush your dead under the carpet?'”

Altitude Films

Altitude FilmsDespite I’m Still Here being mostly set during the dictatorship years, it resonates deeply with Brazilians today.

Brazil is an extremely divided country, and its politics has become exceedingly polarised.

Recent years have seen a rise in extreme rhetoric and efforts to re-write the narrative around the dictatorship.

In 2016, a group of protesters stormed Congress calling for a return to military rule. Three years later, Bolsonaro’s education minister ordered the revision of history textbooks, denying the overthrow of the democratic government in 1964 had been a coup.

Bolsonaro, a former army captain, has praised the former dictatorship and held events commemorating the coup during his time in office.

More recently, Bolsonaro and some of his closest allies have been formally accused of allegedly plotting a coup after he lost the 2022 presidential election.

The former president never publicly acknowledged his defeat and his supporters, who refused to accept the outcome, stormed Congress, the presidential palace and the Supreme Court on 8 January 2023.

Salles told the BBC the current state of politics in Brazil was part of why now was the right time to make the film.

“What’s extraordinary about literature, music, cinema and the arts, is that they are instruments against forgetting,” he said.

‘This trauma is collective’

Marta Costta/Family handout

Marta Costta/Family handoutBrazilians with close ties to the story have described leaving cinemas in tears after watching the film.

Marta Costta, whose aunt Helenira was killed in 1972, said she wanted to run out of the screening.

“You imagine that your family were hooded and tortured in that way,” she told BBC News.

“When Eunice is telling her story, she is also telling mine; when I am telling my aunt’s story, I’m also telling theirs. You can’t separate one from the other,” she said.

Marta is making a documentary about Helenira and her years of resistance, but there is much the family still doesn’t know about her disappearance and death. Helenira’s body was also never recovered.

“It’s a cursed inheritance, because we have to keep passing the baton from generation to generation, until we can ensure her memory is preserved, that history is told how it really happened.”

Helenira’s family will now, 52 years after she was killed, receive a certificate that acknowledges the brutal reality of her death.

Its importance, Marta says, is immeasurable.

“The day we receive that certificate, it’s like the state is recognising its role and apologising.

“It’s the first step for us to be able to begin again.”

Marta Costta/Family handout

Marta Costta/Family handoutThough the certificates are a step forward, both Tessa and Marta say the bereaved families have a long way to go in their fight for justice.

An amnesty law, which remains in place, means that none of the military officials in power at the time or those accused of torture and killings have been prosecuted. Many have already died.

There has been no formal apology from the government or the military.

“Brazilian society needs to recognise this history so these deaths weren’t in vain,” Tessa said.

“If we don’t work to clear up this history, to acknowledge our pain,” Marta said, “we will always be under the risk of it happening again.”

The wounds of the dictatorship, in Tessa’s words, are a national trauma.

But for her, as for Marta and Eunice, it is also a deeply personal history.

“I will not stop fighting until the end of my days,” she said.

“I will bury my father.”

I’m Still Here is out in UK cinemas on 21 February 2025

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source