Climate Change Crisis Nonacceptance — Global Issues

PORTLAND, USA, Sep 19 (IPS) – Many people around the world, especially those among the political far-right, do not accept the climate change crisis. Over the years their thinking, behavior, and policies dismissing climate change have largely continued and impaired global efforts to address global warming and environmental degradation.

The unequivocal findings of numerous reports on the consequences of climate change by international and national scientific committees have not been sufficient to counter climate change skepticism. On the contrary, the reactions of skeptics to the climate change reports can be summed up in the phrase “Don’t confuse me with the facts”.

The rise of right-wing populism in many countries also constitutes a potential obstacle to addressing climate change. Right-wing parties and politicians frequently voice climate change skepticism, denials, and opposition to climate change policies, such as carbon taxes.

The nonacceptance of the climate change crisis persists despite its increasingly visible worldwide consequences. It’s indeed difficult to avoid news reports of climate change events, including extreme heat, flooding, droughts, destroyed crops, wildfires, melting glaciers, rising sea levels, biodiversity loss, environmental degradation, smog, pollution, and increasing rates of human morbidity and mortality.

Even the signed petitions to government leaders from thousands of scientists from around the world warning of a climate emergency and the concerns, demonstrations, and protests of younger generations calling for urgent action have not been enough to convince skeptics of the climate change threat, especially among the political right.

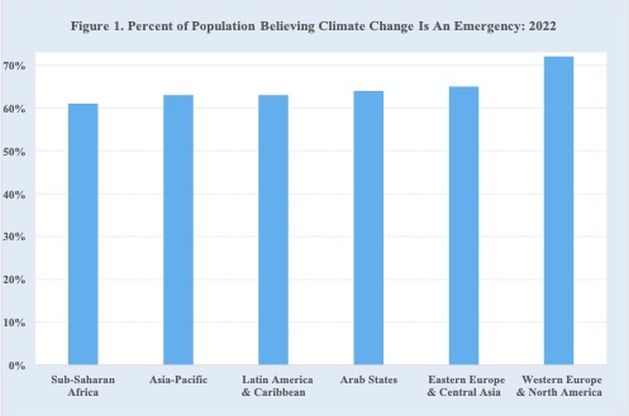

In general, the majorities of most populations are concerned about the climate change crisis. A global survey by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) of public opinion in 2021 covering 50 countries and over half of the world’s population found that nearly two-thirds of those surveyed believed climate change is a global emergency.

The proportion of the population believing climate change is an emergency ranged from a low of 61 percent in sub-Saharan Africa to a high of 71 percent in Western Europe and North America. The proportions of the remaining four regions varied from 63 to 65 percent (Figure 1).

In addition to the UNDP study, a 2022 PEW survey of nineteen countries across North America, Europe, and the Asia-Pacific region found a median of 75 percent viewing global climate change as a major threat to their country.

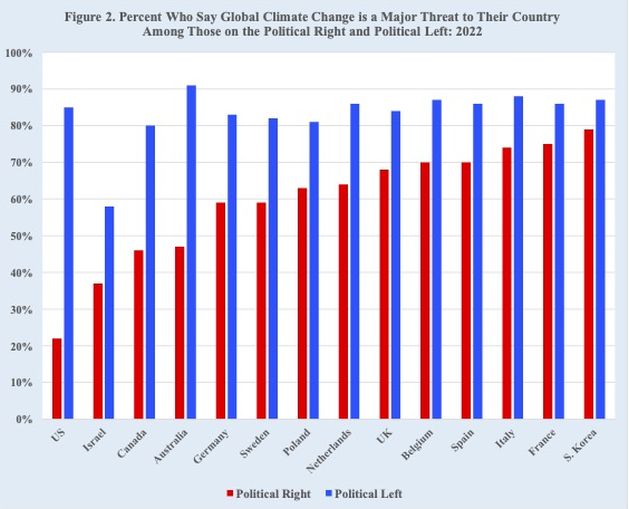

However, views concerning the climate change threat differed considerably across political groups. By and large, surveys find that those of the political right are less likely than those of the left to believe in the reality and anthropogenic nature of the climate change crisis.

In the 2022 PEW survey, for example, those on the political right in fourteen countries were found to be consistently less likely to consider climate change a major threat to their country than those on the political left (Figure 2).

The largest difference among those fourteen countries was in the United States where 22 percent of the political right considered climate change a major threat to their country versus 85 percent on the political left. Other countries with a large difference between those on the political right and left were Australia with 47 and 91 percent, Canada with 46 and 80 percent, and Germany with 59 and 83 percent, respectively.

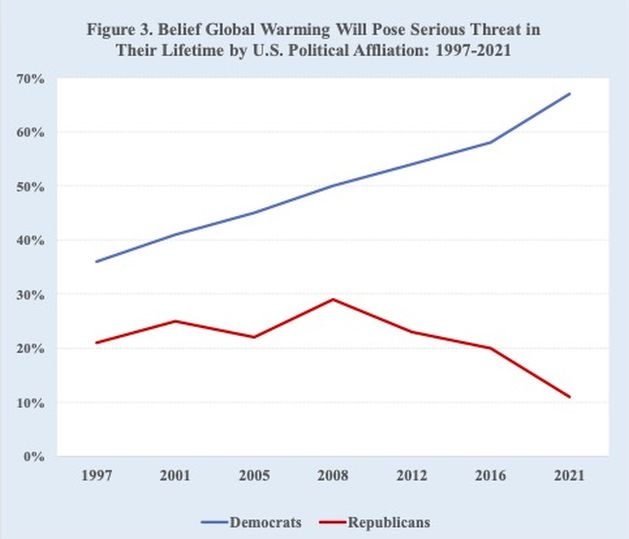

Moreover, the differences in the views of political groups concerning climate change in some major countries have widened over the recent past. In the United States, for example, the difference between Republicans and Democrats has increased substantially over the past quarter century.

Near the start of the 21st century 20 percent of Republicans and 36 percent of Democrats believed that global warming will pose a serious threat in their lifetime. By 2021, the difference between Republicans and Democrats had widened substantially to 11 percent versus 67 percent, respectively (Figure 3).

Also, differing views about climate change are reflected in the statements and policies of political parties and their leaders. For example, the Vox party in Spain dismissed climate change as “a hoax”, the National Front in France promoted climate skepticism, and Sweden’s Democrats described the climate debate as “weird” in budget discussions, arguing that the seriousness of climate change is exaggerated, and scientific evidence is being distorted.

In Germany the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) challenged the global scientific consensus on climate change, describing it as “hysteria”. In addition, the AfD abandoned the previous cross-party consensus on the findings of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

In the United States, the world’s second largest emitter of CO2 producing about 14 percent of the world’s CO2 emissions, the former Republican president said that he was not a believer in man-made global warming, called climate change “a hoax” invented by China, and said scientists were “misleading us” on climate change. Moreover, he dismissed federal scientific reports on climate change and sought to roll back climate regulations, including increasing U.S. coal mining and reconsidering fuel efficiency standards for vehicles.

In China, the world’s top emitter of CO2 producing about 30 percent of the world’s CO2 emissions, some report that the Communist Party’s climate change skeptics are mostly shunned and may chatter in the shadows. After decades of rejecting climate change and its visible consequences, such as choking smog hanging over most of the country, no higher-up Chinese officials are saying that climate change is a hoax and while some may have that view, they won’t say it.

In India, which the IPCC highlights as a vulnerable hotspot, some find politicians denying or ignoring climate change. They note that in the election manifestos of the two leading national parties, the Indian National Congress and the BJP, neither of them mentioned the Paris Climate Change Agreement. Also at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, India reportedly found the IPCC’s recent report too gloomy and requested a section on mitigation be removed.

A preliminary draft of the Glasgow pact called on countries to “accelerate the phasing out of coal and subsidies for fossil fuels”. In the final negotiations, however, India and China, whose coal-fired power stations provide approximately 70 and 60 percent of their electricity, respectively, said they would agree only to “phase-down unabated coal” and the phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.

In addition, when heading to COP26, Australia, Japan, and Saudi Arabia were among those countries lobbying the United Nations “to play down the need to move rapidly away from fossil fuels”. Some wealthy nations also questioned paying more to poorer states to move to greener technologies.

In preparatory meetings for the November COP27 climate summit in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, African nations pushed back against abrupt moves away from fossil fuels. They stressed the need to avoid approaches that encourage abrupt disinvestments from fossil fuels, which would threaten Africa’s development. For example, Nigeria, Africa’s largest population, indicated that gas was a matter of survival for the country.

The latest report of the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) shows greenhouse gas emissions are continuing to rise. The IPCC report also states that current plans to address climate change are not ambitious enough to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, which is a threshold necessary to avoid even more catastrophic impacts.

A number of social and psychological explanations have been offered for climate change crisis nonacceptance and skepticism, especially among the right-wing conservatives. In the past, the lack of knowledge about the causes of climate change was believed to play a major role. More recently, political ideology and party identification are believed to strongly influence how people selectively seek and interpret information about climate change.

Political beliefs and motivations have also been found to guide people’s attention, perceptions, and understanding of climate change evidence and mitigation efforts. In addition, some are not willing to accept the climate change crisis and proposed mitigation measures because they challenge their need to protect existing socioeconomic structures and traditional lifestyles, raise their anxieties about declines in living standards, and threaten development efforts, particularly in less developed countries.

In sum, it is certainly the case that the majority of most populations worldwide, especially the younger generations, are concerned about the climate change crisis. However, it is also the case that despite the overwhelming unequivocal evidence, many people, especially far-right conservatives, continue their nonacceptance of the climate change crisis.

Such a political divide with vocal opposition from the political far-right with the continuing support, political lobbying, and extensive efforts of various extractive industries is worrisome and consequential. It undermines global plans to address climate change and thwarts more ambitious efforts to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, the goal set in the Paris Agreement to avert the worst effects of global warming

Joseph Chamie is a consulting demographer, a former director of the United Nations Population Division and author of numerous publications on population issues, including his recent book, “Births, Deaths, Migrations and Other Important Population Matters.”

© Inter Press Service (2022) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source