Acute Hunger an Immediate Threat To Over a Quarter of a Billion People — Global Issues

ROME, May 14 (IPS) – While King Charles III’s coronation in Britain was hogging much of the international media’s attention at the start of this month, it was easy not to notice another story that deserved at least as many headlines.

According to the latest Global Report on Food Crises (GRFC), the number of people experiencing acute hunger, meaning their food insecurity is so bad it is an immediate threat to their lives or livelihoods, rose to around 258 million people in 58 countries and territories in 2022.

That was an increase from 193 million people in 53 countries and territories in 2021 and it means that the number of people requiring urgent food, nutrition and livelihood assistance has increased for the fourth consecutive year.

It is important to stress here that we are not talking about the number of people around the world who are hungry – a figure that is far higher. Every July the United Nations gives an estimate of the number of people experiencing chronic hunger, meaning they do not have access to sufficient food to meet their energy needs for a normal, active lifestyle, in The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) report and last year’s, referring to 2021, put the figure at 821 million.

The GRFC report, on the other hand, regards only the most serious forms of hunger.

It said that people in seven countries experienced the worst level of acute hunger, Phase 5, at some point during 2022, meaning they faced starvation or destitution. More than half of those people were in Somalia (57%), while such extreme circumstances also occurred in Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Haiti, Nigeria, South Sudan and Yemen.

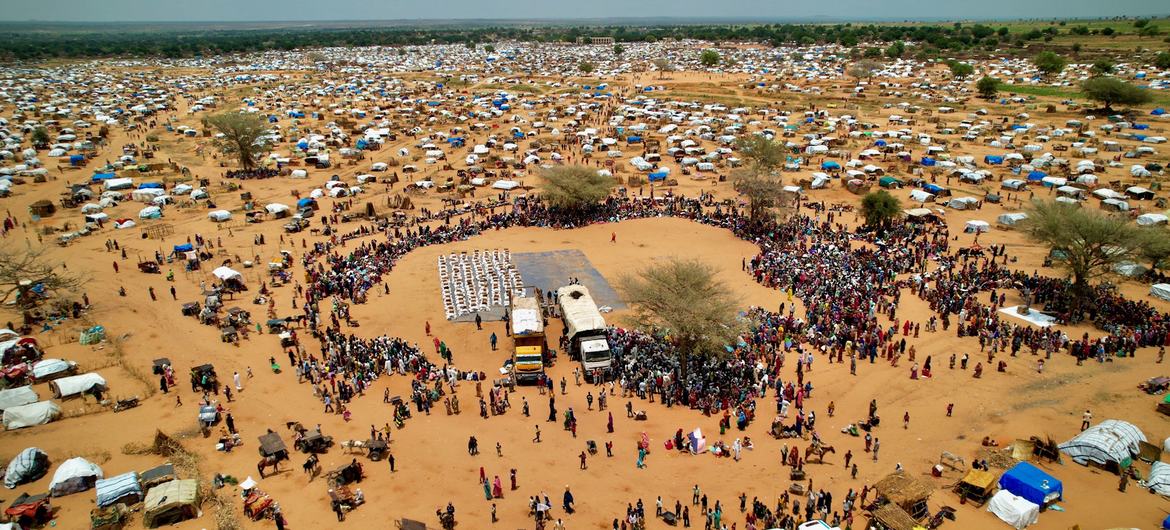

The report said that around 35 million people experienced the next-most-severe level of acute hunger (emergency level, Phase 4) in 39 countries, with more than half of those located in just four – Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sudan and Yemen.

The rest of the acute-hunger sufferers were Phase 3, crisis level.

The 258 million figure is the highest in the history of the report and the situation is getting even worse this year

“More than a quarter of a billion people faced acute food insecurity in 2022 – a year that saw the number of people facing food crises rise by a third in just 12 months,” James Belgrave, a spokesperson for the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP), which is part of the Global Network Against Food Crises (GNAFC) that publishes the GRFC report, told IPS.

“And if we look at how 2023 has gone so far, we see that a staggering 345 million people are facing high levels of food insecurity in 79 of the countries where WFP works.

“This represents an increase of almost 200 million since pre-pandemic levels of early 2020, highlighting just how rapidly the situation has worsened.

“As the World Food Programme marks its 60th anniversary in 2023, we find ourselves in the midst of the greatest and most complex food security crisis in modern times”.

Indeed, the GRFC report has only been published for seven years but it has already documented a big increase in the number of people suffering the worst forms of hunger in that time. The number of people experiencing Phase 3 hunger or above was less than half its current level, at 105 million, in 2016.

In 30 of the 42 main food-crisis situations analysed in the report, over 35 million children under five years of age were suffering from wasting or acute malnutrition, with 9.2 million of them had severe wasting, the most life-threatening form of undernutrition and a major contributor to increased child mortality

Although some of the growth in the severe-hunger figure in the latest GRFC report reflects an increase in the populations of the countries analysed, the fact that the proportion of people in those countries experiencing acute food insecurity increased to 22.7% in 2022, from 21.3% in 2021, demonstrates that the situation is getting significantly worse regardless of demographic factors.

The report said that the main drivers of acute food insecurity and malnutrition were economic shocks, conflict and extreme weather events, which are increasing because of the climate crisis.

It said economic shocks were the biggest drivers last year, although the lines between these factors are blurred as all three affect each other, with climate change feeding conflict, for example, and conflict leading to economic shocks.

In 2022, the economic fallout of the ?OVID-19 pandemic and the ripple effects of the war in Ukraine were major drivers of hunger, particularly in the world’s poorest countries, mainly due to their high dependency on imports of food and agricultural inputs.

The central problem is that much of the world’s population is vulnerable to such extremal shocks, in part because efforts to bolster the resilience of poor small-holder farmers in rural areas and fight food insecurity have proven insufficient.

The report says nations and the international community should focus on more effective humanitarian assistance, including anticipatory actions and shock-responsive safety nets, and scale up investments to tackle the root causes of food crises and child malnutrition, making agrifood systems more sustainable, resilient and inclusive.

“The global fight against hunger is going backwards, and today the world is facing a food crisis of unprecedented proportions, the largest in modern history,” Belgrave said.

“Millions of people are at risk of worsening hunger unless action is taken now to respond together – and at scale – to the drivers of this crisis.

“Life is getting harder each day for the world’s most vulnerable and hard-won development gains are being eroded.

“WFP is facing a triple challenge – the number of acutely hungry people continues to increase at a pace that funding is unlikely to match and the cost of delivering food assistance is at an unprecedented high because food and fuel prices have increased.

“In countries like Somalia, which have been on the brink of famine, the international community, working with government and partners, has shown what it takes to pull people back.

“But it is not sufficient to just keep people alive, we need to go further, and this can only be achieved by addressing the underlying causes of hunger and focusing on banishing famine forever.

“We must work on two fronts: saving those whose lives are at risk while providing a foundation for communities to grow their resilience and meet their own food needs”.

© Inter Press Service (2023) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

Check out our Latest News and Follow us at Facebook

Original Source